“We are committed to:

“Integrity – We will conduct ourselves with integrity in our dealings with and on behalf of the [organization].

“Excellence – We will conscientiously strive for excellence in our work.

“Accountability – We will be accountable as individuals and as members of this community for our ethical conduct and for compliance with applicable laws and [organizational] policies and directives.

“Respect – We will respect the rights and dignity of others.”

This is a Values Statement taken from an organization’s web site. On the surface, it would seem pretty clear.

But what do you do if there’s a conflict between values? What if an employee is excelling in sales, but is disrespectful to co-workers in the process?

What about integrity? What if someone in your company was able to do well for the company as a result of inside information? And what would you do if you found out afterthe company benefited in a substantial way? Where does integrity stand, then?

As I mentioned in Monday’s piece, (March 2), ethics requires more than good faith and clear and concise words. It requires a strong commitment along with a consciousness of ethical issues in our daily lives. It also requires reasoning and problem-solving skills necessary in dealing with those issues.

The Josephson Institute has developed a three-step, decision-making model that can be utilized for common problems:

- All decisions must take into account and reflect a concern for the interests and well-being of all stakeholders. Who will be helped, who will be harmed by the action you are about to take?

- Core ethical values and principles always take precedence over non-ethical values.

- It is ethically proper to violate an ethical value only when it is clearly necessary to advance another true ethical value which, according to the decision-maker’s conscience, will produce the greatest balance of good in the long run.

Example: The ethical value of loyalty is important in relationships where family, friends and co-workers expect allegiance, fidelity and devotion. However, “…one has no right,” Michael Josephson says, “to ask another to sacrifice their ethical principles in the name of loyalty. Loyalty does not justify violation of other ethical values such as integrity, fairness and honesty.”

To further break this down, Josephson offers five steps to principled reasoning:

- Clarify – determine precisely what must be decided. Formulate and devise the full range of alternatives (i.e. things you could do). Eliminate patently impractical, illegal and improper alternatives. Examine each option to determine which ethical principles and values are involved.

- Evaluate – If any of the options require the sacrifice of any ethical principle; evaluate facts and assumptions carefully. Take into account the credibility of the sources of information and the fact that self-interest, bias, and ideological commitments tend to obscure objectivity and affect perceptions about what is true. Carefully consider the benefits, burdens and risks to each stakeholder.

- Decide – After evaluating the available information, make a judgment about what is or is not true, and about what consequences are most likely to occur.

- Implement – Once a decision is made on what to do, develop a plan of how to implement the decision in a way that maximizes the benefits and minimizes the costs and risks.

- Monitor and Modify – An ethical decision-maker should monitor the effects of decisions and be prepared and willing to revise a plan or take a different course of action, based on new information.

Of course, this represents only a condensed list of key points. Any organization that wishes to adopt a standard of ethics needs to engage in ethics training, the kind that involves all employees utilizing real-world scenarios.

Thinking back on my training with Michael Josephson fourteen years ago, one statement he made continues to stand out in my mind:

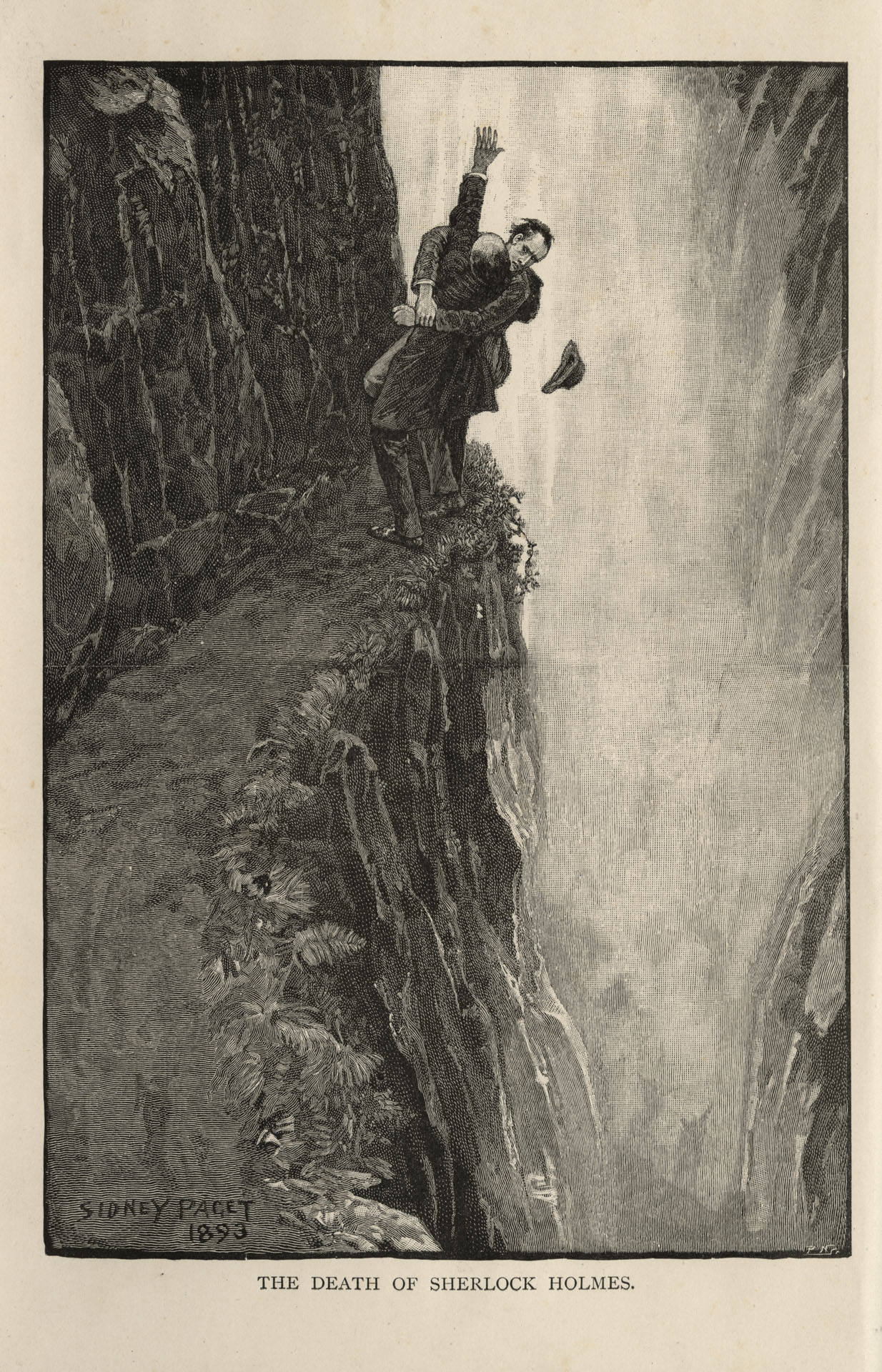

“Remember, we judge ourselves by our best intentions, our most noble acts, our most virtuous habits. But we are judged, and for that matter, we judge everyone else, by our last, worst act.”

Comments