In 1927, Sinclair Lewis gave America a character it did not want to recognize in the mirror: Elmer Gantry.

Gantry is loud, magnetic, insatiable — a sinner with a capital “S.” He does not discover faith; he discovers its usefulness. He learns that fear, properly stirred, can fill a sanctuary. Redemption, properly marketed, can build an empire.

Gantry bellows and sweats. He thunders about sin. He calls for repentance with a finger pointed outward, not toward a scapegoat, but toward his congregation.

“Search your hearts,” he demands.

He does not relieve them of guilt. He intensifies it. He understands that fear is a currency. Feed it, and it multiplies. Convince people that the danger lies within, in their weakness, their moral compromise, and they will cling to the loudest voice promising purification.

He tells them they are the problem, then he offers himself as the cure.

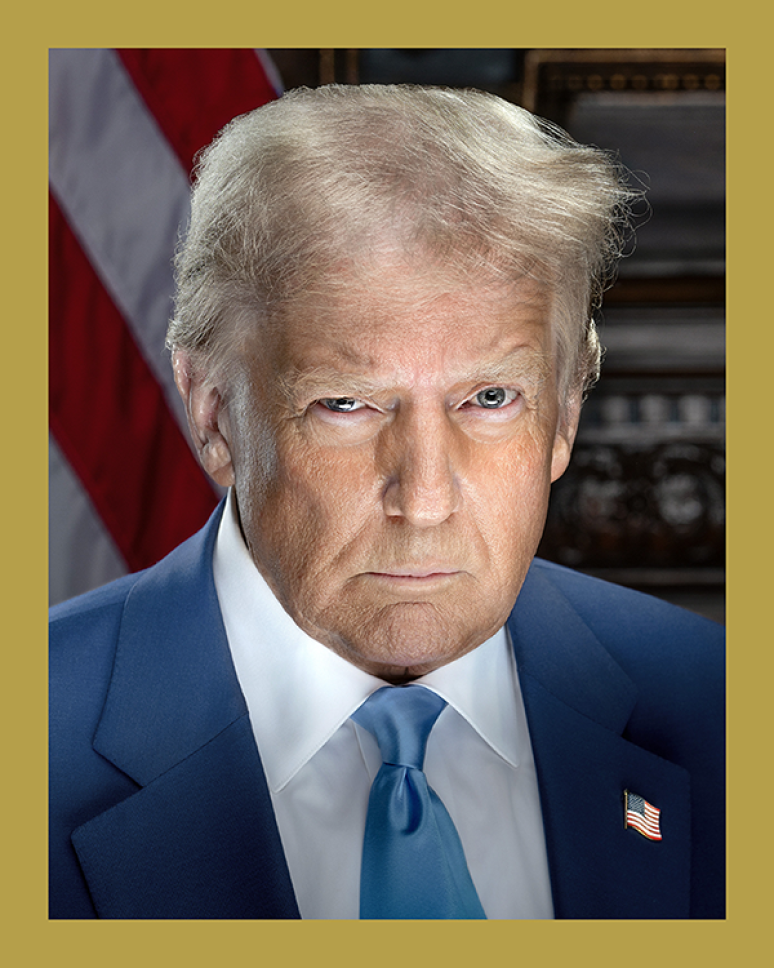

The remarkable thing about Gantry is not that he sins. It is that he sins without consequence in the eyes of those who adore him. His vanity becomes strength, piety becomes performance, and his faith becomes manipulation.

He does not need to be virtuous. He needs only to perform virtue convincingly enough that others suspend disbelief.

And they do.

Lewis was not merely satirizing a corrupt preacher. He was exposing a recurring temptation, the seduction of power cloaked in righteousness. The leader who declares moral decay everywhere but in himself. The voice that substitutes volume for virtue and spectacle for substance.

Crowds gather not because they are foolish, but because certainty is comforting. Because anger feels powerful. Because spectacle is easier than conscience.

The tragedy in Elmer Gantry is not that such a man exists. Men like him have always existed. The tragedy is that language is twisted, and faith itself is recruited into the service of ego.

When Scripture shields appetite, and the altar serves ambition, something sacred is not being practiced; it is being corrupted.

Revelation, in the biblical sense, means unveiling.

What Lewis unveiled nearly a century ago was not simply a fraudulent preacher. He revealed something about us: our willingness to confuse confidence with character.

“And he deceiveth them that dwell on the earth…” — Revelation.

The enduring danger is not only the deceiver. It is the willingness to be deceived.

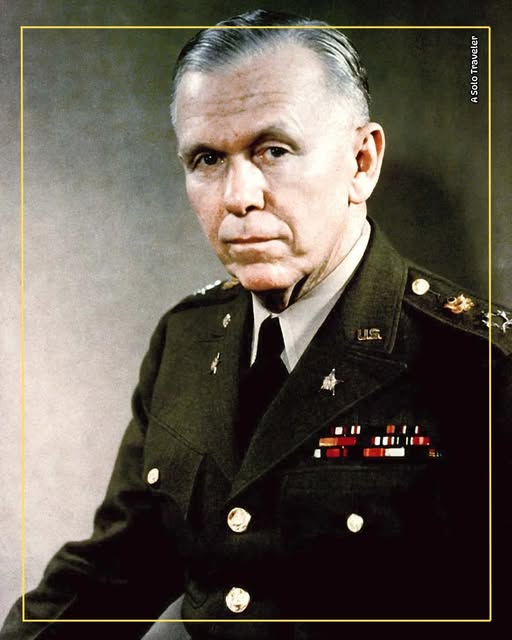

We have seen this pattern before. The leader who declares the nation fallen and himself uniquely chosen to restore it. The man who speaks of strength while demanding loyalty. Who treats criticism as heresy. Who turns grievance into gospel and applause into absolution.

He does not ask for humility. He asks for allegiance.

He does not model repentance. He demands it from others.

And crowds gather. Not because history failed to warn us, but because the warning is always easier to recognize in hindsight than in the present moment, when character no longer matters and spectacle substitutes for substance. That’s the moment a democracy begins to bargain with its own conscience.

That is not merely a literary lesson. It is a civic one.