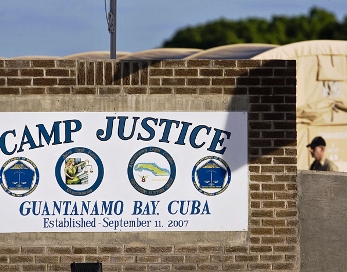

On Wednesday I asked if it was ethical to force-feed prisoners at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, who, by their own volition, refused to take any nourishment. The question was featured in a Room for Debate forum on The New York Times website.

I was looking for responses based solely on the ethics of such an action. I pointed out that both the American Medical Association as well as the World Medical Association state that “Where a prisoner refuses nourishment and is considered by the physician as capable of forming an unimpaired and rational judgment concerning the consequences of such a voluntary refusal of nourishment, he or she shall not be fed artificially.”

However, one graph earlier in the same document, it states that “The physician’s fundamental role is to alleviate the distress of his or her fellow human beings, and no motive, whether personal, collective or political, shall prevail against this higher purpose.”

This would seem to contradict their position that upholds a prisoner’s right to autonomy. A number of experts weighed-in on the question.

Steven S. Spencer is a former medical director of the New Mexico Corrections Department:

“I’ve been the responsible physician in cases where force-feeding inmates became necessary. So this is an ethical issue to which I have given a great deal of consideration. The hunger-striking prisoner may be willing to die in pursuit of his goal. But the stress of incarceration may distort reasonable thinking.

“Despite concerns for patient autonomy, to withhold treatment, or to fail to intervene with forced feeding, to my mind would violate the norms of medical ethics.

“The responsible physician has a clear professional obligation to obtain thorough medical and psychiatric evaluations and to monitor weight loss and other parameters of deteriorating health in an appropriate medical setting like an infirmary. There is a need for patient education and compassionate counseling. The inmate patient needs to be informed regarding expected changes in his condition. He must also be informed that when his life is in danger involuntary treatment in the form of forced feeding will take place. Treatment of other medical problems must be provided if and when they occur during the fast.”

Brian Mishara, a professor of psychology, is the director of the Center for Research and Intervention on Suicide and Euthanasia at the University of Quebec in Montreal:

“In the situation of a hunger strike like that of the detainees at Guantánamo Bay, the objective is political, and the hope of the person is that his action will result in a change in his situation. It may also be true that those involved in the hunger strike would rather die (commit suicide) than endure in the current circumstances….

“In the case of Guantánamo, intervening to save or prolong a person’s life without trying to change the person’s reasons for wanting to die cannot be considered suicide prevention. Suicide prevention would involve intervening to change the person’s desire to die (despite his circumstances) or changing the situation that he feels is intolerable.

“From the news reports I have seen, those steps are both absent, and therefore the military’s force-feeding does not constitute suicide prevention. It could be ethical to force-feed prisoners – to buy time – but not if that is the whole plan. It would have to be part of a larger intervention to change the circumstances and the desire to die.”

Ann Gallagher is the director of the International Center for Nursing Ethics, at the University of Surrey, in England:

“Health professionals regularly make decisions about the continuation and discontinuation of treatment and they have to accept patients’ decisions to refuse treatment even if this may result in their deaths. The right to refuse medical interventions to provide nutrition and hydration should also be extended to prisoners as autonomous individuals.

“We must have the utmost respect for nurses and other professionals who work ethically in military and custodial care settings and appreciate the many challenges that arise. We must also express our solidarity with those who refuse to do something that conflicts with their professional values.

“Nurses who refuse to participate in force-feeding are, in my view, acting in accord with their professional values. Force-feeding is not part of nurses’ caring repertoire.

“Moreover, there cannot be a health care solution to a political problem.”

Vincent Warren is the executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represented clients in two Guantánamo Supreme Court cases:

” ‘The government will keep us alive by force-feeding us,’ a Guantánamo prisoner said to one of our lawyers recently, ‘but they will let us die by detaining us forever.’

“The hunger strikers we have met with tell us they are not trying to kill themselves. They are refusing to eat because it is the only way they can peacefully protest their continual imprisonment without charges. They haven’t given up on their freedom.

“In the words of Sabry Mohammed, a Yemeni who, like most of the inmates, remains detained years after the Obama administration approved his release: ‘I don’t want to die. I want to return to my family. But I have been pushed too far.’

“It is a universally accepted international norm that force-feeding a prisoner who has made a voluntary and informed decision to stop eating violates medical ethics.”

My perspective: Clearly, in the case of the hunger-striking Guantánamo prisoners, it is difficult to entirely remove the political aspect from the equation.

Having said that, I would have to consider the stakeholders involved: the prisoner, his family, attending doctors and nurses. However, due to world political ramifications, I find it difficult to exclude political leaders in such a decision.

Although the ethical value of responsibility is important in such a decision, respect appears to carry the highest priority. Recognizing and honoring each person’s right to autonomy and self-determination seems to be critical in such a situation. While I would attempt to talk-through the decision with a prisoner, I would ultimately have to honor his wishes, providing he was deemed capable and responsible for making such a decision.

Taking it a step further, since President Obama has effectivelyordered the military to force-feed the most critical prisoners, I would find myself in the difficult decision of either following orders or perhaps being court-martialed for insubordination.

Despite orders from a commander-in-chief, I would risk a court-martial in order to uphold what I believed to be the most reasoned ethical option and oppose force-feeding any prisoner.

Is it the right action? You tell me.

Comments