Moral relativists won’t lose any sleep over this one.

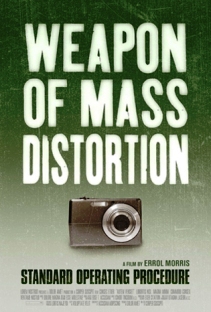

Academy Award-winning documentary filmmaker Errol Morris (“The Fog of War,” “The Thin Blue Line”) has apparently pulled off another controversial winner with his new film “Standard Operating Procedure” which examines the abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq at the hands of our own military.

This time, however Morris got a little more controversy than he may have bargained for when it was revealed that some of the U.S. soldiers who took part in the abuse were paid for their interviews in the film.

“I paid the ‘bad apples’ because they asked to be paid,” Morris said, “and they would not have been interviewed otherwise.” Beyond his brief statement at New York’s Tribeca Film Festival, Morris would not reveal which soldiers were paid or how much.

Standard operating procedure for the majority of American news divisions has held that you do not pay interview subjects because of the real concern that the money may cause the truth to be enhanced or manipulated.

However, according to a New York Times article, Executive Vice-President of Participant Productions Diane Weyermann said, “It’s not all that uncommon [paid interviews]; it’s just something most people don’t talk about.” Participant Productions helped finance “Standard Operating Procedure.”

Morris’ and Weyermann’s justifications are more commonly known as the “False Necessity Trap.” The argument goes like this: To find out what really went wrong over there, we need to hear from these people, and because we couldn’t get the interviews any other way, we paid. So what if we paid them. We’re in pursuit of the truth and the end justifies the means.

However, there’s another aspect to the story.

A book tie-in to the film authored by Morris and Philip Gourevitch is due for release on May 15 by Penguin Press and the book was adapted in a recent New Yorker magazine article in which some of the paid interviews appear.

New Yorker editor David Remnick said, “When stuff is done as first-order material for The New Yorker… it [pay for an interview] is never done. And if it was done, I wouldn’t publish it, period.”

The New York Times: “Mr. Remnick said that he had been unaware that Mr. Morris had paid interview subjects for their time, and noted that the material came to the magazine at one degree of remove.”

One degree of remove does not “remove” the money from the person paid for their interview, much less alter the potential for an enhanced or manipulated story.

Tom Rosenstiel, director of the Project for Excellence in Journalism (PEJ), a non-profit group that examines the work of the news media said, “If you pay people for a story, you create an incentive for them to make it more dramatic than the facts might bear out.”

In countering the so-called “pursuit of truth” argument that Morris suggests, the PEJ has, on its website, nine principles of journalism, (www.journalism.org). Under the first principle, “Journalism’s First Obligation is to the Truth” is this:

“Journalists should be as transparent as possible about sources and methods so audiences can make their own assessment of the information. Even in a world of expanding voices, accuracy is the foundation upon which everything else is built–context, interpretation, comment, criticism, analysis and debate. The truth, over time, emerges from this forum. As citizens encounter an ever greater flow of data, they have more need–not less–for identifiable sources dedicated to verifying that information and putting it in context.”

The New York Times reported, “…Mr. Morris expressed some ambivalence about whether these payments should have been disclosed in the film.”

“‘I perhaps should have,’ Mr. Morris said about disclosing the payments… [But] ‘Without these extensive interviews, no one would ever know their stories.”

Perhaps we may never know the full truth behind their stories.

Comments