Since the terrorist attack against the French satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo (Jan. 7), in which 12 individuals were murdered, there’s been no shortage of opinion writers denouncing the assault as an attack on freedom of expression. But can satire go too far?

Dictionary.com defines satire as “the use of irony, sarcasm, ridicule, or the like, in exposing, denouncing, or deriding vice, folly, etc.”

That satire can come in the form of images and words.

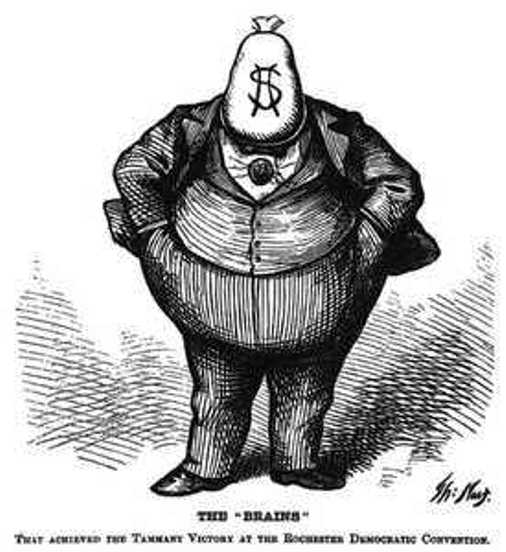

Thomas Nast, the German-born American political cartoonist, rose to fame in the 1870’s for his satirical attacks against New York’s infamous William “Boss” Tweed and his Tammany Hall gang of corrupt politicians. In looking at the above drawing entitled, “The Brains,” the depiction meant to portray the fat-cat commissioner of public works as being totally controlled by money, which, in fact, was true.

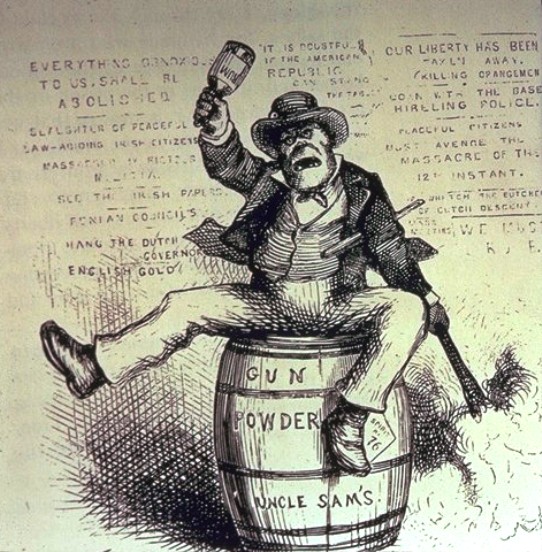

While Nast’s perfect use of satire ultimately led to the downfall of Tweed and his cronies take a look at this second Nast cartoon, entitled, “The Usual Irish Way of Doing Things.” In a heavily footnoted entry in Wikipedia, “Nast considered the Roman Catholic Church a threat to American values, and often portrayed the Irish Catholics and Catholic Church leaders in hostile terms.” Did Nast go too far in his depiction of the Irish?

In her 2012 book, “Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons,” Fiona Deans Halloran suggests that much of cartoonist’s work was informed by his experience. In 1863, for example, Nast “witnessed the New York City draft riots,” Wikipedia writes, “in which a mob composed mainly of Irish immigrants burned the Colored Orphan Asylum to the ground. His experiences may explain his sympathy for black Americans and his ‘antipathy to what he perceived as the brutish, uncontrollable Irish thug.’ ”

Clearly, there is a fine line between satire that ridicules for the sake of change, and satire that crosses into wanton disrespect and xenophobic rants.

“…amid all the ‘I Am Charlie’ marches and declarations on social media,” writes Jennifer Schuessler in The New York Times (Jan. 10), some in the cartooning world are also debating a delicate question: Were the victims free-speech martyrs, full stop, or provocateurs whose aggressive mockery of Islam sometimes amounted to xenophobia and racism?”

“Public reaction to the attack in Paris has revealed that there are a lot of people who are quick to lionize those who offend the views of Islamist terrorists in France,” writes NY Times columnist David Brooks (Jan. 9), “but who are a lot less tolerant toward those who offend their own views at home.

“Just look at all the people who have overreacted to campus micro-aggressions. The University of Illinois fired a professor who taught the Roman Catholic view on homosexuality. The University of Kansas suspended a professor for writing a harsh tweet against the N.R.A. Vanderbilt University derecognized a Christian group that insisted that it be led by Christians.

“Most societies,” Brooks says, “have successfully maintained standards of civility and respect while keeping open avenues for those who are funny, uncivil and offensive. In most societies, there’s the adults’ table and there’s the kids’ table.

“The people who read Le Monde or the establishment organs are at the adults’ table. The jesters, the holy fools and people like Ann Coulter and Bill Maher are at the kids’ table. They’re not granted complete respectability, but they are heard because in their unguided missile manner, they sometimes say necessary things that no one else is saying.”

I’ve written about Coulter before, whose purpose is to promote herself by saying something offensive, just to say something offensive.

While Bill Maher has crossed the line, as well, Maher is billed as a comedian; Coulter bills herself as a social and political commentator with the goal of expressing ideas that promote change. Coulter is, in fact, the resident Narcissus of political commentary.

According to Tom Spurgeon, the author of The Comics Reporter, Charlie Hebdo appears to be from the Coulter mold, “a much more savage, unforgiving, doing-it-for-the-sake-of-doing-it.” Spurgeon believes “there’s a sophisticated dialogue about what privilege means, and a feeling that you don’t need to insult people, especially downtrodden people, to make your points.”

A recent (Jan. 10) New York Times “Room for Debate” asks “Can writers and artists sometimes be too provocative and outrageous? Should they hold themselves back?”

Amos N. Guiora, a professor at S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah argues, “The essence of liberal society is critical thinking, robust dialogue and open exchange of ideas… Charlie Hebdo published cartoons deemed offensive to Islam. That is true. So what? Journals publish articles, satire and cartoons that offend other faiths and ethnicities. That is what satirists and cartoonists do.”

Science fiction and fantasy writer, Saladin Ahmed asks, “…are there times when writers, particularly satirists, should check our own tongues? When sensitivities are high, should artists self-censor?

“The fact is, we self-censor and select the targets of our satire based on our worldviews – and those worldviews are influenced profoundly by being male or female, black or white, American or Iraqi, Muslim or Christian. Our identities and lived experiences have everything to do with the offenses we decide need mocking, and the targets that we select.”

Satire can be funny and sarcastic, rude and insensitive. The best satire not only holds the mirror up to nature, but reminds us how we can be better.

Comments