Without a doubt, last year was the year the news media and politics fused into a kind of “Kardashian” alt-reality of over-the-top, dramatic nonsense that turned logic on its head.

However, I want to go back in time, revisiting an event that took place in Boston, because I think there are some interesting parallels to the 2016 presidential campaign.

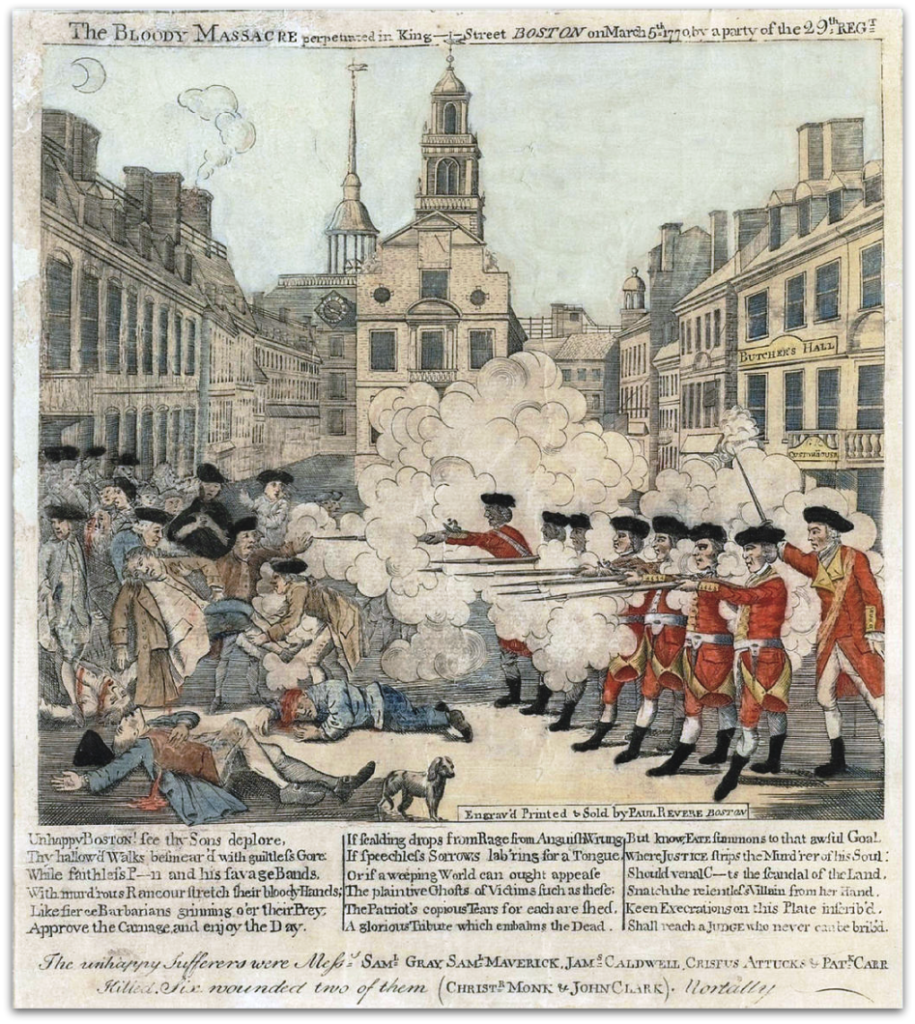

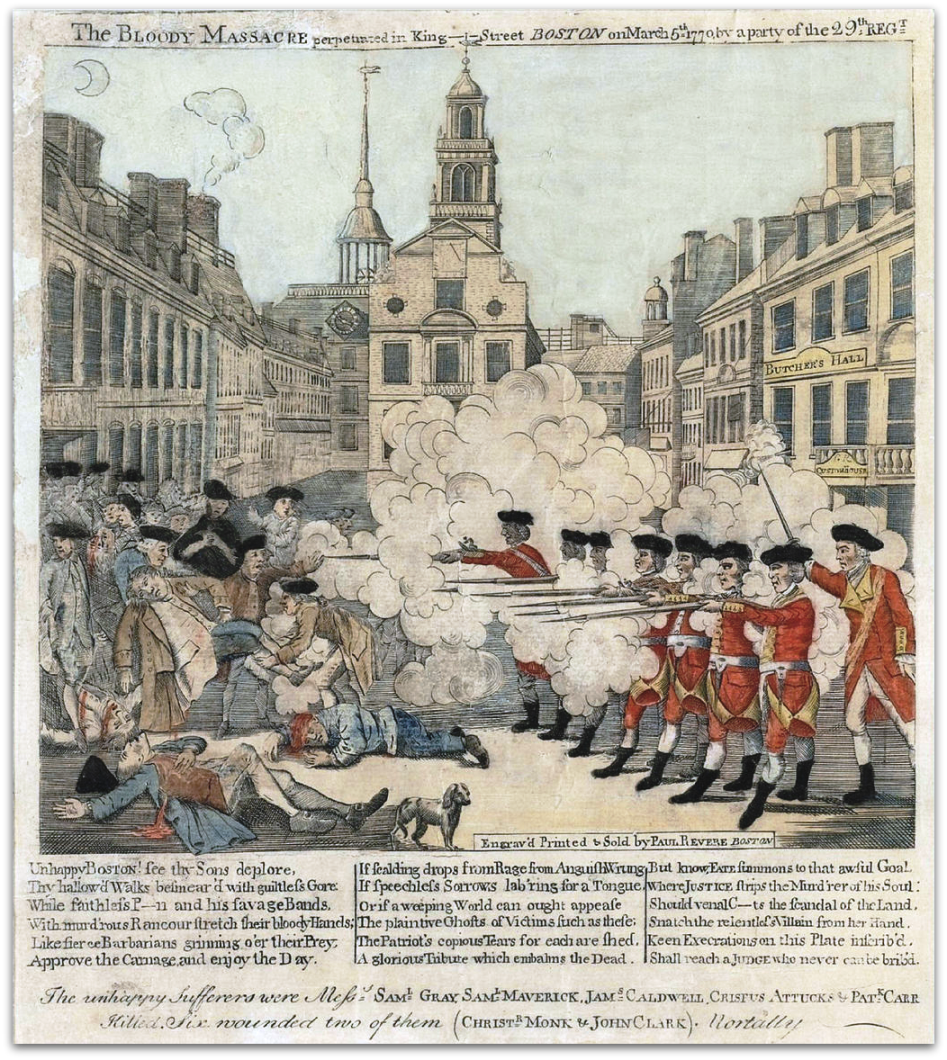

On March 5, 1770, a group of British soldiers in Boston shot and killed five citizens and injured six others. The incident came to be known originally as “The Bloody Massacre,” and soon after, “The Boston Massacre” due, for the most part, to a widely circulated broadside, or poster – the social media of its day – engraved by American patriot Paul Revere.

While the graphic, and accompanying text, helped fire up the revolution to come, nonetheless, it was a cagey piece of political “spin”; in other words, misinformation.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History makes note of a number of inconsistencies to the actual event.

– The British are lined up and an officer is giving an order to fire, implying that the British soldiers are the aggressors.

– The colonists are shown reacting to the British when in fact they had attacked the soldiers.

– British faces are sharp and angular in contrast to the Americans’ softer, more innocent features. This makes the British look more menacing.

– The British soldiers look like they are enjoying the violence, particularly the soldier at the far end.

– The colonists, who were mostly laborers, are dressed as gentlemen. Elevating their status could affect the way people perceived them.

– There is a distressed woman in the rear of the crowd. This played on eighteenth-century notions of chivalry.

– There appears to be a sniper in the window beneath the “Butcher’s Hall” sign.

– Dogs tend to symbolize loyalty and fidelity. The dog in the print is not bothered by the mayhem behind him and is staring out at the viewer.

– Crispus Attucks is visible in the lower left-hand corner. In many other existing copies of this print, he is not portrayed as African American.

– The soldiers’ stance indicates an aggressive, military posture.

The reality was unlike the broadside. Britain’s King George III had posted some 4,000 British soldiers in Boston to enforce the Townshend Acts, a somewhat universal tax on all manner of goods coming to the colonists from England. With Boston citizens already angered by the taxes, things quickly went from bad to worse.

In his Pulitzer-prize-winning book, John Adams, David McCullough describes the scene on that fateful night in March.

“…a lone British sentry, posted in front of the nearby Custom House, was being taunted by a small band of men and boys. The time was shortly after nine [in the evening]. Somewhere a church bell began to toll, the alarm for fire, and almost at once crowds came pouring into the streets, many men, up from the waterfront, brandishing sticks and clubs. As a throng of several hundred converged at the Custom House, the lone guard was reinforced by eight British soldiers with loaded muskets and fixed bayonets, their captain with drawn sword. Shouting, cursing, the crowd pelted the despised redcoats with snowball, shucks of ice, oyster shells and stones. In the melee the soldiers suddenly opened fire, killing five men.

“Samuel Adams [cousin to John] was quick to call the killings a ‘bloody butchery’ and to distribute a print published by Paul Revere vividly portraying the scene as a slaughter of the innocent, an image of British tyranny, the Boston Massacre, that would become fixed in the public mind.

“The following day,” McCullough continues, “thirty-four-year-old John Adams was asked to defend the soldiers and their captain, when they came to trial. No one else would take the case, he was informed. … Adams accepted, firm in the belief, as he said, that no man in a free country should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial, and convinced, on principle, that the case was of utmost importance. As a lawyer, his duty was clear. That he would be hazarding his hard-earned reputation and, in his words, ‘incurring a clamor and popular suspicions and prejudices’ against him, was obvious, and if some of what he later said on the subject would sound a little self-righteous, he was also being entirely honest.”

In his closing remarks to the jury – edited by his wife Abigail – at the second trial held for the eight soldiers, Adams gave what is considered to be a brilliant defense of facts versus speculation, rumor and innuendo.

“[Adams] described,” McCullough continues, “how the shrieking ‘rabble’ pelted the soldiers with snowball, oyster shells, sticks, ‘every species of rubbish,’ as a cry went up to ‘Kill them! Kill them!’ One soldier had been knocked down with a club, then hit again as soon as he could rise. ‘Do you expect he should behave like a stoic philosopher, lost in apathy?” Adams asked. Self-defense was the primary canon of the law of nature. …

“ ‘Facts are stubborn things,’ [Adams] told the jury, “and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictums of our passions, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.’

“Of the eight soldiers, six were acquitted and two found guilty of manslaughter, for which they were branded on their thumbs.

“As time would show,” McCullough concludes, “John Adams’s part in the drama did increase his public standing, making him in the long run more respected than ever.”

The “Boston Massacre” broadside clearly demonstrates the power popular media can have to sway an already angry public looking for change regardless of the specific facts.

It’s interesting to compare the drama in 1770 Boston to the drama served up by both mainstream and social media in 2016. And that’s what I’ll explore in the next commentary.

Comments

Leave a Comment

Your excellent study introduced many of us to a, heretofore unknown event. It prompted me to dig deep into “our massacre” while I was in Viet Nam as a surgeon: the March 16, 1968 murder by a company of undisciplined U.S. soldiers at My Lai. (We never heard about it except by “scuttlebutt.”)

More than 500 women and children were shot with Captain Medina and Lt. Calley not just tolerating the action, but participating. Calley was the ONLY one found guilty and served less than a year in a stockade. They were part of “The Americal Division” which operated up North in II Corps, and were considered undisciplined and poorly trained even before the “incident” by officers with whom I associated in The First Cavalry Airborne, The Big Red One, and the great 9th Division in the Delta.

Cover-ups extended all the way to generals — one who later was the Superintendent at West Point — when they finally got to him, and busted from two to one star and dismissed.

Had it not been for a brave Army photographer, in a circling helicopter, who got his guys on the ground and trained their big rockets and heavy machine guns on the perpetrators, [My Lai] might have gone on until dark. He received the “Soldier’s Medal” for his bravery, about as low an award as one can get.

So, this stuff has always existed. War brings out the beast in even ordinary people.

And, that sniper in the window… [in the “Boston Massacre” broadside] …either superb “Cover” or my magnifying glass needs more power.