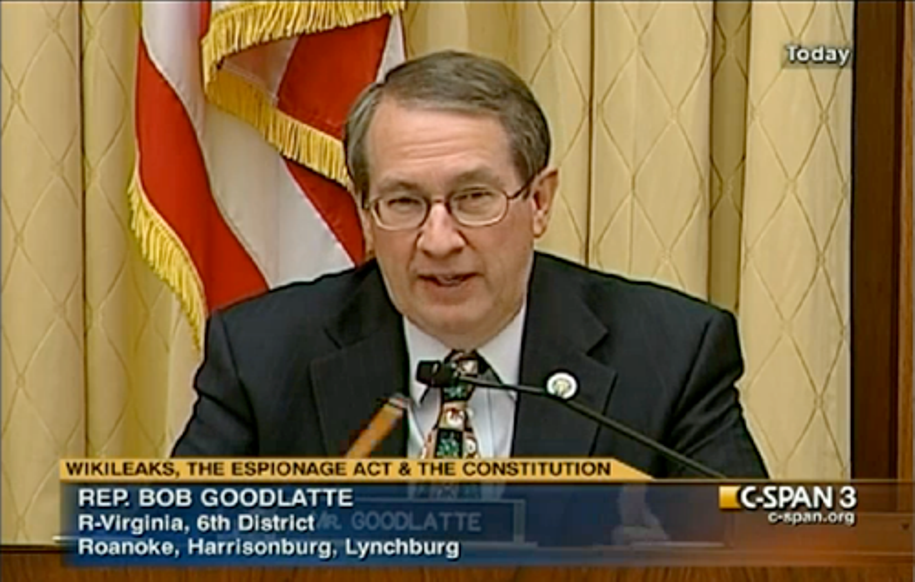

Like millions of voters, I awoke Tuesday to news that – absent public debate or even advance notice – Republican Congressman Robert Goodlatte and others decided that they were going to gut the power of The Congressional Office of Ethics.

Front page of The Wall Street Journal (Jan. 3): “House Republicans, meeting as a group Monday night, approved an amendment from House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte (R., Va.) that would place the office under the oversight of the lawmaker-run House Ethics Committee.

“The Office of Congressional Ethics serves as the chamber’s independent ethics watchdog,” The Journal continues, “by reviewing allegations against House members and staff. It is currently governed by an eight-person board of private citizens who don’t work for the government.”

“The House Republicans’ move,” The New York Times said (Jan. 3), “would take away both power and independence from an investigative body, and give lawmakers more control over internal inquiries.”

(I didn’t need my morning espresso.)

Immediately, I began drafting an e-mail to send to every member of the House about this issue, ready to send them off when I returned from my morning workout. I returned, however, to news that, “facing a storm of bipartisan criticism, including from President-elect Donald J. Trump, [House Republicans] moved early Tuesday afternoon to reverse their plan to gut The Office of Congressional Ethics.”

“The reversal,” The Times writes in a follow-up, “came less than 24 hours after House Republicans, meeting in a secret session, voted, over the objections of Speaker Paul D. Ryan, to eliminate the independent ethics office. It was created in 2008 in the aftermath of a series of scandals involving House lawmakers, including three who were sent to jail.

“Republicans, led by Representative Robert W. Goodlatte of Virginia, had sought to prevent the quasi-independent ethics office from taking up investigations that might involve criminal charges, and they wanted to grant lawmakers on the more powerful House Ethics Committee the right to shut down any of the inquiries. They also wanted to block the small staff at the Office of Congressional Ethics from speaking to the news media.

“ ‘It has damaged or destroyed a lot of political careers in this place, and it’s cost members of Congress millions of dollars to defend themselves against anonymous allegations,’ Representative Steve King, Republican of Iowa, said on Tuesday, still defending the move.”

However, Leo Wise, OCE’s first director in 2008, responded:

“This is a fact-gathering operation. All it does it gather facts,” says Wise… “The idea that [the members are] being abused by this doesn’t make any sense.”

“Unlike other similar agencies,” the website Vox writes (Jan. 3), “the OCE can’t issue sanctions. It can’t force members of the House to testify or turn over evidence and documents. Congressional members ultimately retain authority over its decisions. The OCE can’t even say if it thinks a member of the House did something wrong.

“What the OCE can do is much simpler: issue fact-based reports through investigations conducted by the attorneys on its staff. (The investigations are authorized and approved by an eight-member board of directors, mostly composed of former legislators.) Unlike a stalemated partisan body, the OCE is a bipartisan and independent commission that acts free of political interference.”

Vox journalist Jeff Stein interviewed Wise.

Stein: “Why was the OCE created in the first place, and what was its purpose?”

Wise: “The OCE was created in the wake of the [Jack] Abramoff–related corruption scandals, and it was born of a desire to introduce transparency into an ethics process that lacked it.

“For the first time, it opened a way for the public to bring concerns of House members’ behavior — and for the public to get to see what the members had done related to potential misconduct.”

Stein: “And so why didn’t the existing process — the investigations through the House Ethics Committee — take care of that?”

Wise: “One of the real deficiencies with the existing process was how secretive the process was. There was so little transparency or accountability for how the ethics process worked; unlike other congressional committees, the ethics committee doesn’t operate in public or make any kinds of public reporting of what they’ve found and what they’ve done.

“There was a raft of scandals being addressed by law enforcement and investigative journalism, but there was a black box within the institution itself that had the responsibility to police its members. The effort was made to shine light into that black box and give the public a way to see whether there were facts in support of these allegations — and to see how members and staff were behaving within the institution.

“There are inspectors general in nearly all federal agencies. And they do internal reviews, audits, investigations — and they issue detailed reports to the public describing how those agencies are run and a good way to reduce waste, fraud, and abuse in the executive branch.

“There was nothing like that in the House. There’s an inspector general, but it has a very narrow and circumscribed mandate because it only pertains to the contracting process. This was akin to that, but for ethics.

“It doesn’t find people guilty of committing crimes or breaking the law; it gathers facts and presents them to the public. This was an exercise in fact-finding in a way that the decision-makers in the House — so we can produce the facts, and then everyone can draw their own conclusions.”

In 2010, when attempts by both Republicans and Democrats were undertaken to dismantle the Office, the nonprofit, nonpartisan Sunlight Foundation wrote, “More than anything else the Office of Congressional Ethics has helped to reveal to the public the patent absurdity of the self-policing oversight that members provide through the House Ethics Committee.”

At the end of the day, what’s it all about… CLASS?

It’s Accountability, Stupid!

Comments