U1897.1.1 George Washington as Colonel in the Virginia Regiment, Charles Willson Peale, 1772. Washington-Custis-Lee Collection, Washington and Lee University, Lexington VA – mountvernon.org

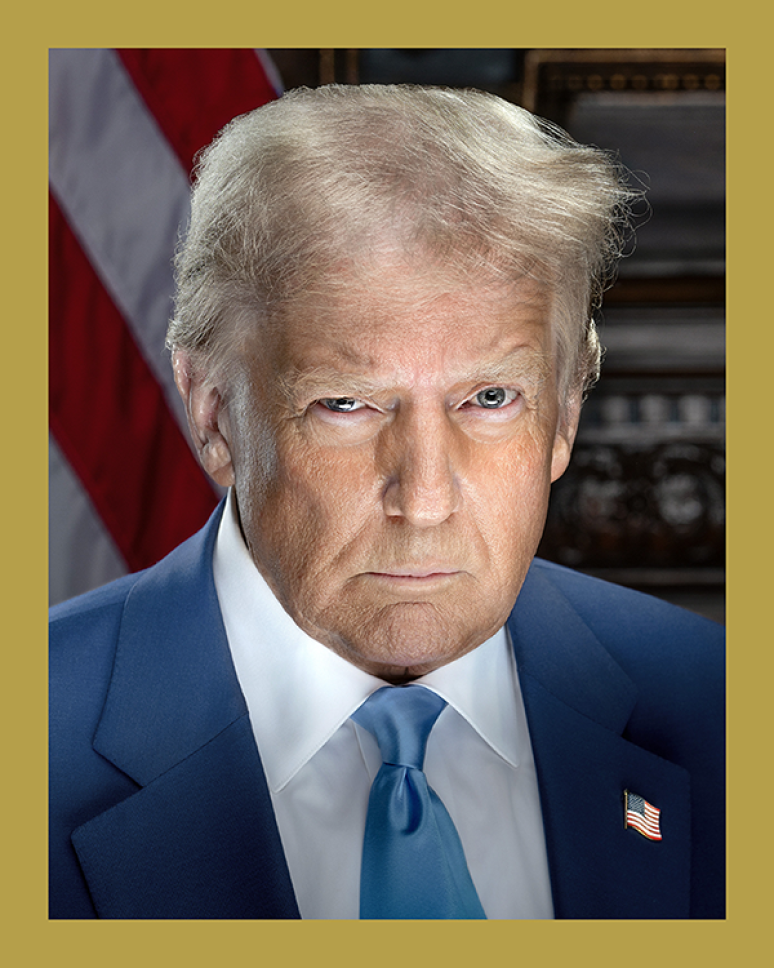

How do we reconcile the integrity of a leader to whom service to the country was exemplary, but held slaves in service to him?

Washington D.C. is far too often remembered for its scandals than its triumphs—a reality that would have stunned and saddened our first president. Yet history’s true measure lies with those who chose conscience over expedience, and duty over ambition. Their choices came at a cost, but they show us what integrity in public life looks like—and how it can still guide and inspire our own. After more than thirty years writing and speaking about ethics, I know how rare—and how necessary—that kind of courage remains.

For me, the leader who embodied unquestionable character and honor was George Washington—the man who could have been king. Twice he walked away from power: first in 1783 when he resigned his military commission after the Revolution, then again in 1796 when he refused a third presidential term.

Yet Washington wasn’t a perfect man. While he advanced the practice of civic virtue, he fell short on liberty for all. He enslaved more than 100 men and women while leading a republic founded on rights. The law and economy of his day enabled it; his own choices sustained it. Late in life, his moral compass shifted as he arranged to free those he personally owned and provide for their welfare—but only after his death.

Still, Washington’s greatness lay not in perfection but in evolution. He wrestled—quietly but earnestly—with the contradiction between the ideals he helped define and the reality he lived. His private writings reveal a man uneasy with injustice, aware of the distance between principle and practice. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he took steps—however limited—to reconcile that conflict in the only way he understood. His legacy reminds us that integrity is not the absence of fault but the willingness to confront it—to grow in understanding and to act, however late, on what conscience demands.

Historically, while we honor the precedent Washington set for constitutional duty, it’s important to tell the full truth about the people whose labor made his household possible. That tension is not a footnote to his integrity; it’s a test of ours.

Nonetheless, in an era when leaders clung to authority, Washington demonstrated that public service was service, not entitlement. His restraint set the model for democratic leadership.

We cannot excuse its absence. We must demand its presence.

Comments