In a letter to the Danbury Baptists in 1802, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God … I contemplate with sovereign reverence … thus building a wall of separation between Church & State.”

In my commentary, “When Power Rewrote the Message” (July 17), I opened with this question: “When the pulpit merges with power, does the sword overshadow the Sermon on the Mount?”

Christian nationalism seems to answer that question with a resounding… Yes. It takes the language of faith and splices it with politics. The cross becomes a campaign logo; the Bible a prop for power. In this version, Christianity is less about compassion, humility, and justice—the core of the Sermon on the Mount—and more about control, exclusion, and authority.

The term Christian nationalism has become so widespread in recent years that I spent some time digging a little deeper.

This new version of Christianity claims that America’s future depends on one faith, one vision, one set of beliefs. But that runs directly against the principle the Founders wrote into the First Amendment: government has no business imposing religion, and religion has no business holding the power of government.

James Madison, the Father of the Constitution, wrote: “Religion & Govt. will both exist in greater purity, the less they are mixed together.” He understood that when faith and government merge, both are corrupted. Religion loses its moral authority, and government loses its impartiality. Instead of guiding us toward justice, it twists faith into a tool of power and politics into a battlefield of belief.

As Christ himself taught in the Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called the children of God” (Matthew 5:9). Yet Christian nationalism too often turns that blessing on its head, replacing peacemaking with sword-rattling, and humility with the hunger for control.

It also ignores one of the clearest moral imperatives of that same sermon: “Whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets” (Matthew 7:12). The Golden Rule could not be simpler: treat others as you would want to be treated. Any creed built on exclusion, like Christian nationalism, inevitably collapses in the face of the Golden Rule.

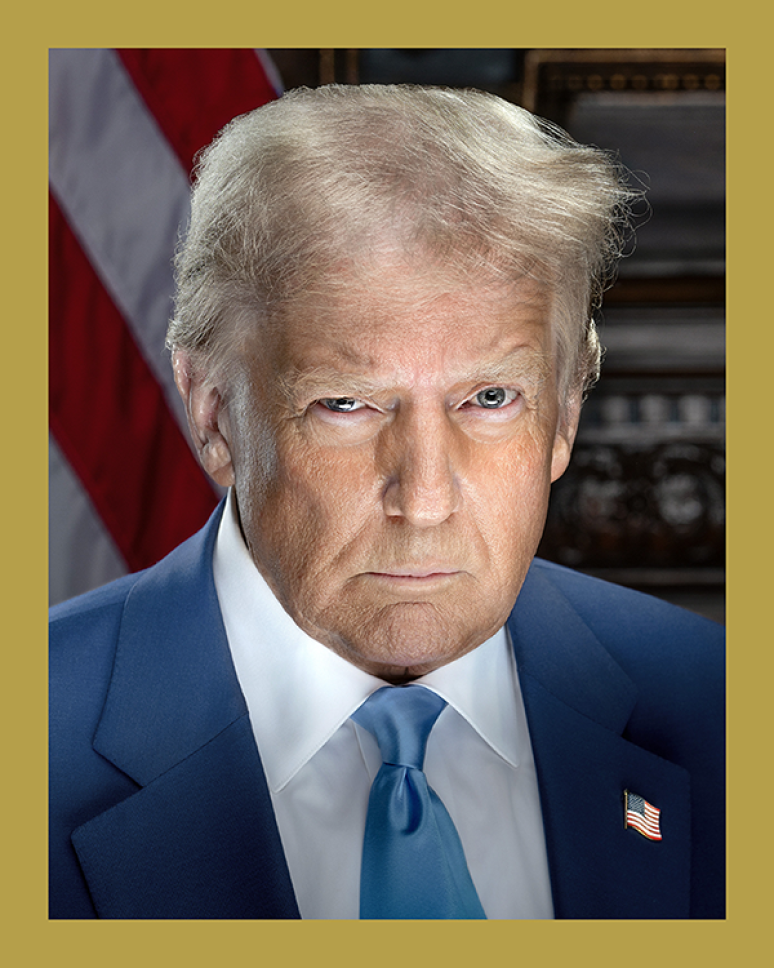

Evangelical author Eric Metaxas told Donald Trump: “Jesus is with us in this fight” to overturn the 2020 election. Then he added, “I’d be happy to die in this fight.” Appearing on Charlie Kirk’s program, Metaxas pushed the rhetoric even further: “We need to fight to the death, to the last drop of blood.”

The ethical inconsistency is glaring. A man who professes allegiance to the teachings of Christ—teachings based on humility, compassion, and peace—invokes Jesus to justify overturning a lawful election and promises bloodshed in His name.

That’s not faith. That’s fanaticism.

Christian nationalism claims to defend Christianity, but in reality it undermines both Christianity and democracy. For democracy to work, all citizens—all citizens—Christian, Jew, Muslim, Hindu, atheist, or anyone else—must be equal before the law, with the same rights and the same voice. To accept less is to turn your back on both the Gospel’s call to peace and the Constitution’s call to equality.

In the end, we either stand for freedom of conscience—or surrender it to those who confuse power with faith.

Comments