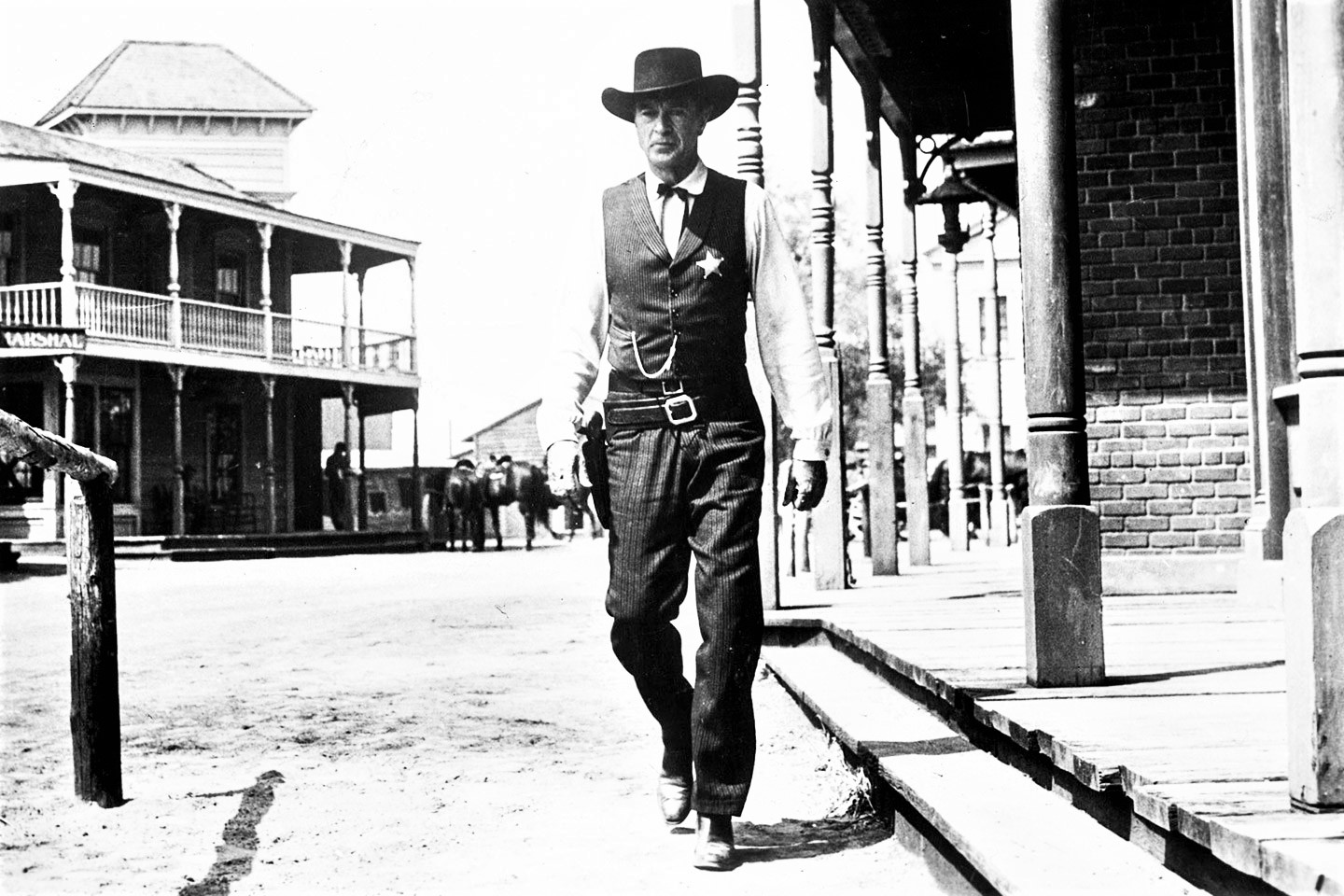

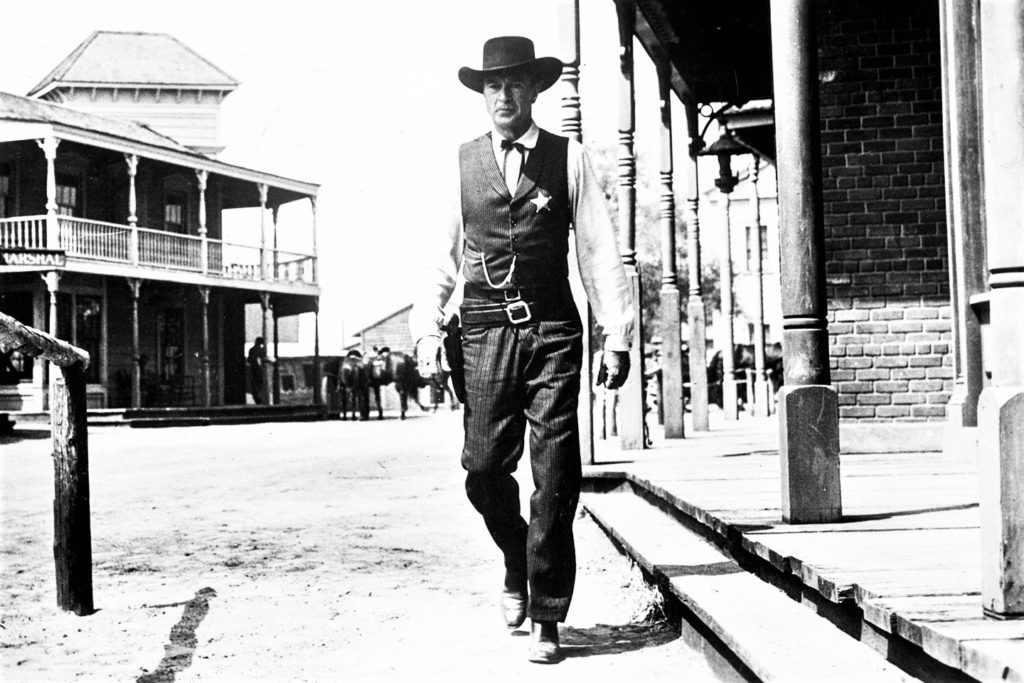

Of all the films whose central character demonstrates a highly developed moral compass, High Noon tops my list. Why does High Noon still matter?

Never has one film captured the essence of an ethical dilemma along with the variety of rationalizations against doing the right thing as this 1952 western does.

Written by Carl Foreman (who was facing his own dilemma with McCarthyism at that time), and starring Gary Cooper, the film’s hero Marshal Will Kane is asked to make a difficult choice. After a brief marriage ceremony, Kane learns that Frank Miller, a murderer he sent to prison, has just been pardoned and due to arrive on the noon train with revenge at the top of his “to do” list.

Legally, Kane is under no obligation to stay. In fact, the town’s selectmen absolve him of any responsibility even as they help him aboard the buggy with his new wife and quickly usher him out of town.

However, on that short trip out of town, he has a chance to think.

“It’s no good,” Kane tells his wife. “I’ve got to go back.”

“Why?”

“They’re making me run. I’ve never run from anybody before.”

“I don’t understand any of this,” she tells him.

Strapping on his gun and badge, he explains. “I sent a man up five years ago for murder. He was supposed to hang. But up North, they commuted it to life and now he’s free. I don’t know how. Anyway, it looks like he’s coming back.”

“But that’s no concern of yours, not anymore,” she tells him. “They’ve got a new marshal.”

“He won’t be here until tomorrow. Seems to me I’ve got to stay.”

From an ethical point of view, Kane is the archetypal Kantian protagonist who believes that he has an absolute duty to stay and defend the town.

Act that your principle of action might safely be made a law for the whole world.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant believed that ethical obligations are “higher truths” which must be honored regardless of the consequences and/or conflicting impulses.

“I’m not trying to be a hero,” Kane tells his wife. “If you think I like this, you’re crazy!”

Even Kane’s mentor and former sheriff shows him the cynical side of being a lawman: “You risk your skin catching killers and the juries turn them loose so they can come back and shoot at you again.”

“You’re a judge!” Kane tells his colleague in an effort to reason.

While the ‘learned’ judge knows the law, he’s well-acquainted with reality: “Have you forgotten what he is? Have you forgotten what he’s done to people?… Nothing that happens here is really important. Now get out.”

“There isn’t time,” Kane answers.

What he’s really saying is, “I have no choice. I have to stay.” While others equivocate the issue, Kane’s choice is black and white, much like the film’s black and white photography which is a stark reflection of the character’s conscience.

Hadleyville is a moral town with moral people. While some argue for responsibility: “You all ought to be ashamed of yourselves. I tell ya, if we don’t do what’s right, we’re gonna have plenty more trouble.”

Others find it easier to pass the buck: “Yes, we all know who Miller is, but we put him away once. And who saved him from hanging? The politicians up North. I say this is their mess.”

When faced with a choice between courage and fear, even the town’s moral leader, the minister, feels conflicted: “The commandments say, ‘Thou shalt not kill,’ but we hire men to go out and do it for us. The right and the wrong seem pretty clear here. But if you’re asking me to tell my people to go out and kill and maybe get themselves killed, I’m sorry. I don’t know what to say. I’m sorry.”

Don’t be fooled by its simple plot, sparse dialog and modest action. High Noon is filled with all manner of ethical action questions: How important is it to stay and defend a town that refuses to help itself? What responsibility do you owe your family? And what kind of bargains should you make in trade for the help you need?

Loyalty, duty, caring, respect, justice, integrity: What makes High Noon relevant is how it takes on universal themes of character and conscience, duty and honor.

All of us want to do the right thing. We all want to be the right kind of role model for family, friends, and co-workers. The conflict arises when we’re faced with a choice between what we want, (or don’t want), and who we want to be. More often than not, we hear stories of individuals at their worst: deceitful, irresponsible, corrupt; people who justify and rationalize: “it’s not my job; not my problem; not my fight!”

There are, in fact, many more examples of those who affirm duty, honor and integrity in spite of pressures to do otherwise; people who are selfless in the face of self-interest; reveal courage in the face of fear; and stand on principle even when the odds are against them.

Cynthia Cooper stood up for integrity when she blew the whistle on $11 billion in fraud at WorldCom. Tobacco insider Jeff Wigand stood up against decades of lies told by the tobacco industry. It’s the same kind of principled stand that Secret Service Director Lewis Merletti took against independent counsel Kenneth Starr who was willing to do whatever it took to “get” President Bill Clinton over a sex scandal, even if it meant compromising the safety of the presidency itself.

These are our Will Kane’s; individuals who choose conscience over convenience.

Of course, the real question High Noon asks is, how will we respond when faced with our own Hadleyville? Will we do what’s right or rationalize our way around it?

Why does High Noon still matter?

Because integrity always matters.

Comments