Fifty years ago no one had a clue how the week would end and how it would change us forever.

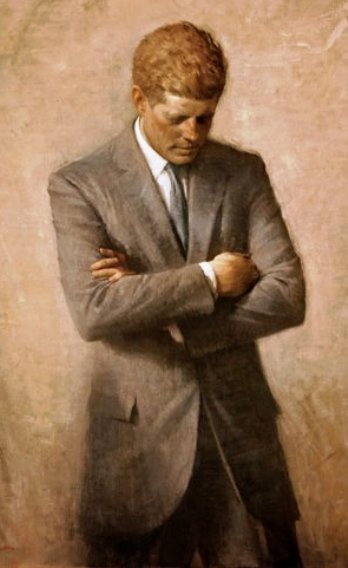

Fifty years later, the mythology surrounding President John F. Kennedy has only grown. In a recent Gallup Poll (Nov. 15), Americans gave Kennedy their highest approval rating, 74 percent, over any of the last 11 presidents since Eisenhower. “That includes,” Gallup writes, “a 2000 measure, in which Kennedy was at the top of the list, eclipsing Abraham Lincoln, Franklin Roosevelt, and Ronald Reagan.”

For me, Kennedy represented a coming-of-age of national awareness. It was the first time I watched, in a classroom, the inauguration of a U.S. President; the first time I recall seeing his family pictured in all manner of national magazines. It was also the first time I remember a president criticized by the press and savaged by his opponents for his lack of experience and choices.

In early November 1963, a week before Thanksgiving, I was a freshman high school student on the east coast in the process of studying Macbeth.

“If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly. If the assassination could trammel up the consequence and catch with this surcease success, that but this blow might be the be-all and the end-all here…”

What struck me most about Kennedy was the fact that we had a president closer to the age of my parents instead of my grandparents. He appeared confident, relaxed and extraordinarily likeable. In spite of the Bay of Pigs disaster in Cuba – brought on by the CIA – and our initial involvement in Vietnam, he stood up to the Russians during the Cuban Missile Crisis one year later. Kennedy may have made mistakes, but he clearly learned from them, and the public, for the most part, backed him.

He rallied support for an army of volunteers known as the Peace Corps whose mission was to travel to underdeveloped regions around the world, and improve conditions in healthcare, farming and education. And he pressed for Civil Rights:

“The denial of constitutional rights to some of our fellow Americans on account of race – at the ballot box and elsewhere – disturbs the national conscience, and subjects us to the charge of world opinion that our democracy is not equal to the high promise of our heritage.”

He also proposed an overhaul of the immigration policy as well as a net tax cut of $10 billion over three years.

Richard Reeves writes in Profile in Power, that the U.S., Great Britain and the Soviet Union, at Kennedy’s urging, agreed to a limited treaty that banned all but underground testing of atomic weapons. After sending the text and analysis of the treaty to former President Harry Truman, Truman replied, “I want to congratulate you… I think it’s a wonderful thing. My goodness life, maybe we can prevent a total war with it.”

One Kennedy-initiated program began with this declaration before Congress in 1961:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

“The New Frontier of which I speak is not a set of promises — it is a set of challenges,” Kennedy said in his presidential nomination acceptance speech. “It sums up not what I intend to offer the American people, but what I intend to ask of them.”

Kennedy lived to witness six of the seven original Mercury astronauts launched into space and safely returned to earth.

Sitting in a classroom studying and discussing the events of the day in Civics, watching a world of possibilities open up before us – even going to the Moon – was so fantastic, it was almost incomprehensible. Kennedy not only believed it was possible but directly inspired its accomplishment.

Why are we still fascinated with John F. Kennedy fifty years after his death?

In spite of the affairs and controversies, Kennedy represented hope and action. He continued to push for the kind of change that lived up to the promise our parents desired for themselves as well as for us.

On the final page of Profiles in Courage, Kennedy still inspires us through words that, in many ways, mirrored his own brief life.

“The courage of life is often a less dramatic spectacle than the courage of a final moment; but it is no less a magnificent mixture of triumph and tragedy. A man does what he must — in spite of personal consequences, in spite of obstacles and dangers, and pressures — and that is the basis of all human morality.

“In whatever area in life one may meet the challenges of courage, whatever may be the sacrifices he faces if he follows his conscience – the loss of his friends, his fortune, his contentment, even the esteem of his fellow men – each man must decide for himself the course he will follow.”

Fifty years later, 61 percent of Americans according to Gallup“…still believe others beside Lee Harvey Oswald were involved” in Kennedy’s assassination.

Fifty years later, I choose to look back on Kennedy’s legacy, not in how he died, but how he lived and what he stood for – our highest aspirations.

Comments