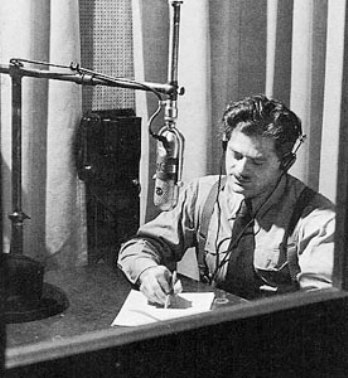

Writers are, for the most part, invisible to the public. Sure there are those exceptions who have used their talent to stand in the spotlight, but Norman Corwin was more focused on his craft than the attention.

Corwin was not just extraordinary with words; he was master of radio, stage and screen. Such a master of radio drama, that Orson Wells stopped whatever he was working on to be part of a Corwin project. Since his death last week, tributes to America’s “poet laureate of radio” have come forth from all the usual literary corners regarding his many achievements. This is a more personal acknowledgement.

I had the great, good fortune to meet Norman a little more than eleven years ago when I asked him and others to contribute to a book of ethical stories. Corwin was the first to respond… byphone, no less. During the first of several initial conversations, I always addressed him as “Mr. Corwin,” not because of his age, rather out of reverence for his immense talent. And each and every time, he corrected me. “Jim, please, it’s Norman.”

It took me eight reminders by Norman before I finally got it. He didn’t want to be put on a pedestal. He wanted to be treated as a colleague.

Not long after that first conversation, a hand-addressed letter came in the mail inviting me to Norman’s 90th birthday party. A private event, I immediately called Norman and asked if it wasn’t a mistake. “You want me at this special event,” I asked.

“Of course,” he said. “I think it’s time we meet in person, don’t you, and” he added, “I’d like to meet your wife, as well.” (In spite of his age, Norman always had his eye out for the ladies, believe me.)

In those days I was writing a series of ethics-related op-eds for a variety of newspapers. I had just finished what I considered to be my best effort. Before sending it out, I thought, maybe Norman could provide some valuable input. I called and he responded. “It’s brilliant,” he said. “Just one suggestion: I would change your repeated litany from ‘Why can’t we,’ to ‘Let’s try.’ It’s more inclusive,” he added.

It didn’t take long to discover the master’s touch. It was the perfect choice of words to make the point without wagging my finger. When I later informed him that all the newspapers I had worked for had turned it down, Norman responded with a note: “It’s their loss.”

In the process of finishing What Do You Stand For? with two of Norman’s contributions, that op-ed became the core of the final chapter. Once complete, I sent a final draft to Norman for his feedback. Not long after, he invited me to lunch at his home. Throughout that lunch we talked about politics, and the Boston Red Sox (we were both fans). But in the back of my mind I kept waiting for his comments on the book. As we finished eating, he began by telling me a story.

In celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Bill of Rights, President Franklin Roosevelt’s office contacted Corwin to write and direct a special radio tribute. The Library of Congress was kept open after hours to accommodate Corwin’s research on the project.

We Hold These Truths would be divided into three parts: the first would begin in Los Angeles with a drama narrated by Jimmy Stewart, featuring, among others, Lionel Barrymore, Walter Brennan, Walter Huston, Edward G. Robinson, Rudy Vallee and Orson Wells; the second part moved to the White House for a personal address by Roosevelt; the program would conclude in New York with NBC’s Leopold Stokowski conducting the New York Philharmonic through the Star Spangled Banner.

On a train headed back to Los Angeles where the principal portion of the program would be broadcast, Norman locked himself in his compartment and began writing the script. At one point, he asked a porter for a portable radio to listen to a rebroadcast of one of his shows.

The porter looked surprised. “There are none to be had. Ain’t you heard?,” the porter said, “the Japs just bombed Pearl Harbor!”

Corwin quickly wired the White House at the next stop: “Just learned of attack on Pearl Harbor. Is the Bill of Rights show still on? Do we even need such a program at this time? Please advise,” signed, Corwin.

When he arrived in Los Angeles, a response from Roosevelt was waiting for him: “We need it now, more than ever!”

At this point, Norman stopped his story, picked up a copy of my manuscript and said, “Jim, we need your book now, more than ever!”

No one else was in the room. Just two writers sitting and talking: one master and one apprentice receiving the tribute of a lifetime.

After acquiring a used copy of More by Corwin a collection of his radio dramas, we met once again for another lunch at his home. I held out a copy of the book and asked if he would sign it for me. “However,” I added, “you will notice that you originally signed this copy ‘For Betsy Geary.’ ”

At 100 years old, without missing a beat, Norman took the book and slowly wrote the following: “To Jim, Never mind Betsy Geary, whoever she is. She will never have your aura. Norman Corwin.”

For your wit, your wisdom, and eleven years of friendship, I sincerely thank you, Norman.

Comments