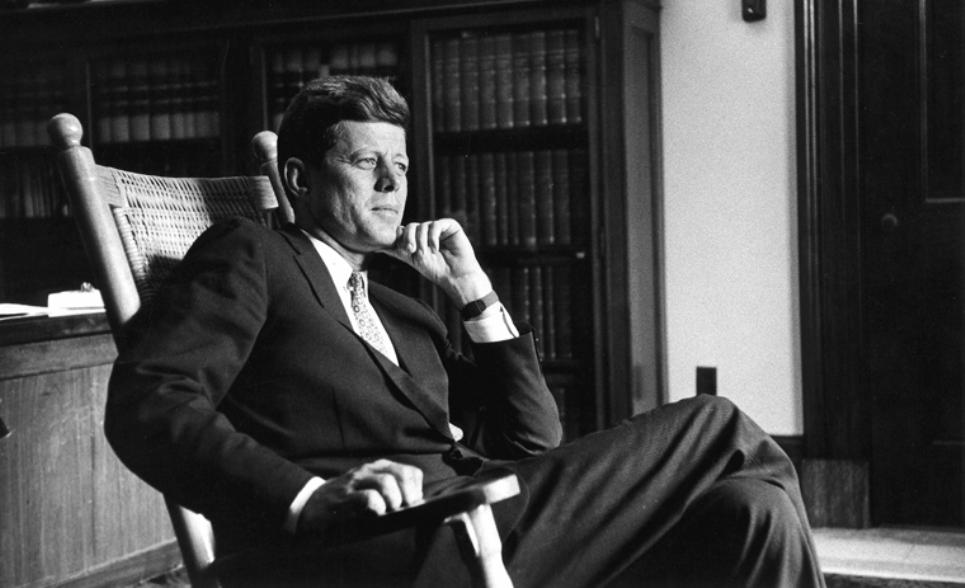

Today would have been the 100th birthday of John F. Kennedy.

While he served less than three years as the nation’s 35th president, more books have been written about Kennedy – 62,000 – than any president in the last 152 years, (Lincoln comes in first with 111,000; Washington, second with 83,000). I have 31 books on Kennedy in my own library, including three different editions of Profiles in Courage.

For me, Kennedy stands out for several reasons: he was the first president I watched inaugurated on television, January 20, 1961; his inaugural speech was the first I studied that same day in my seventh grade civics class; the first time I watched a president explain, again on television, the Cuban missile crisis; and the last whose assassination caused my 10th grade class to be suspended on that dark day in November, 1963.

Over the years, I’ve been drawn to the words of a man I admired due, in large part, to how his words not only reflected the past, but always looked to the future; a future with equal parts optimism and responsibility.

“Let us not seek the Republican answer or the Democratic answer, but the right answer,” Kennedy said in a 1958 speech in Maryland. “Let us not seek to fix the blame for the past. Let us accept our own responsibility for the future.”

While his life was a mix of commendation and controversy, it was his focus on understanding and learning the lessons of history that taught me how valuable that history is. It was Kennedy’s reading of historian Barbara Tuchman’s book, The Guns of August, about the many miscalculations that led to World War I, that moved the president – against the demands of his own generals – to exercise self-restraint during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

One of my favorite books about Kennedy is Counselor. It was Kennedy speechwriter and chief counselor Ted Sorenson’s final book. One chapter responds to a few controversies that have lingered, most notably: what was Kennedy’s motive in writing the book?

In 1954, Eleanor Roosevelt spoke of Kennedy’s absence during a Senate vote to condemn Communist-hunting Senator Joseph R. McCarthy.

“I wish Kennedy had a little less profile and a little more courage,” the former first lady scolded.

She suggests, as others have, that Kennedy wrote Profiles to atone for his absence in voting to condemn McCarthy. However, that’s not entirely accurate.

“When the roll was first called in July 1954,” Sorensen writes, “JFK knew that, if he voted with his fellow Democrats and anti-McCarthy Republicans on a motion to censure McCarthy, he would be defying many in his home state and family; but if he voted against such a motion, he would be denounced by the leading members of his party, by the leading liberals and intellectuals in the country and his alma mater, by the leaders of the Senate, and by the major national newspapers. He would even have trouble with both his conscience and his young legislative assistant [Sorensen]. …

“I prepared for him, at his request, a speech in support of censure. He intended to vote accordingly, when the matter came to the Senate floor on the evening of July 31.”

The Sorensen/Kennedy speech reads in part:

“There are difficulties in explaining the deep-rooted feelings which motivate one on such an issue where so many emotions run high. I am not insensitive to the fact that my constituents perhaps contain a greater proportion of devotees on each side of this matter than the constituency of any other Senator. The zeal with which these citizens view this issue emphasizes their sincere concern for exposing the Communist threat in this country and for combating Communism without adopting its methods… This censure motion, like those previously adopted by the Senate, is more concerned with the dignity and honor of this body than with the personal characteristics of any individual Senator… It is for these reasons… that I shall vote to censure the junior senator from Wisconsin.”

“It was a mild, cautious speech in favor of censure,” Sorensen adds, “but it was still a speech in favor of censure.

“However, he never had an opportunity to deliver it or to cast the vote it foretold. The Senate decided that evening that no such vote should be taken without a special committee investigation and hearing. By the time that committee report was delivered and debated, JFK was in the hospital, effectively incommunicado (or at least with me). I had no contact with him and no instructions. Under Senate rules, I could have registered with the Secretary of the Senate on his behalf an ‘announcement’ or ‘pair’ in favor of censure, in effect casting the vote of a juror who had not been present at the trial, who had not read the report or heard the debate.”

At twenty-six years of age, Sorensen says, having received no guidance from Kennedy or his family members, he made no decision on behalf of his boss.

“McCarthy was a moral issue,” Sorensen adds. “JFK, gravely ill, did not voluntarily absent himself; but neither did he take any steps to make his position public and clear; and I have no doubt that political safety as well as family harmony was a major reason.”

Regardless, Sorensen calls Kennedy’s lack of public response on the McCarthy issue a “failure.”

While he did not always live up to the highest standards he spoke of in speeches, Kennedy did inspire this writer to take a closer look at his own life. The final words in Profiles set forth a critical test for each of us.

“In whatever arena of life one may meet the challenge of courage, whatever may be the sacrifices he faces if he follows his conscience – the loss of his friends, his fortune, his contentment, even the esteem of his fellow man – each man must decide for himself the course he will follow. The stories of past courage can define that ingredient – they can teach, they can offer hope, they can provide inspiration. But they cannot supply courage itself. For this each man must look into his own soul.”

Today, we need moral courage, perhaps as never before; the courage of our convictions, certainly, but the courage to work with others regardless of what political badge they’re wearing; the courage to be accepting and tolerant; and the courage to be the best we can be no matter how others may regard us.

We need that courage, now more than ever.

Comments