Last Friday, President Trump ordered the Department of Justice to investigate the F.B.I. to determine if they implanted an informant to spy on the Trump campaign. There is no evidence to support the president’s allegation.

Many of Trump’s congressional allies, believing that federal investigators may have abused their authority, have demanded that Justice hand over documents about the informant. Until recently, Justice officials have refused claiming that turning over the documents would endanger the source’s safety. Although, the informant’s name has since been revealed through several media outlets, I won’t do that here.

However, I will describe why it is critically important to protect such sources by way of my own minor experience. While I wrote about this in my 1998 book, What Do You Stand For? I was purposely vague on some of the details. After 40 years, I believe I can fill-in a few blanks.

In the early ‘70s, I was working in post-production in Hollywood. Among my many duties was expediting prints at Technicolor, the primary film lab we used. Over the course of two years I had cultivated a reputation of trust among the people at the lab which allowed me to wander in and out of rooms where negatives and prints were stored.

The ‘70s was a time when home video equipment was just being introduced. The equipment, however, was bulky and expensive. At the time, a black market existed for feature film prints. Not the big 35mm prints used in theaters, but the home-friendly 16mm prints. Making and selling those prints was a crime; transporting them across state lines made it a federal offense.

One of my bosses at that time, Peck Prior, was also president of Technicolor. Evidence pointed to a lot of illegal prints coming out of his lab. Because of my affability and access at all times of the day or night, I was asked by his partner, Harry Bring, if I would look into the situation, track down who was involved and how it was done. The notion of playing detective appealed to me. However, I wasn’t prepared for the consequences of that decision.

To my great surprise, it took very little “detecting” on my part to uncover the information. In fact, the man in charge of bootlegging the prints approached me! “If you ever have any interested clients,” he said, “let me know.”

Claiming to have never seen a 35-to-16mm reduction print made, I asked him to show me the process. Late one night, I followed him into the room where the negatives for films in current release were stored. It took me about a week to put everything together.

At this point, however, I was spending more time at night than usual and getting a little concerned about someone knowing who I was and what I was doing. After giving an update on my progress, I asked Harry if others were involved in helping catch the thieves. He assured me that my information was but one piece of corroborating information.

Around that time, I had been invited to a company picnic. The bootlegger and his family also attended. The man had become a friend and seemed sincerely devoted to his wife and kids. This was in a time, as well as a business, where I observed more than a little marital cheating going on.

The following Monday, I was contacted by an F.B.I. agent on the case who came into my office and shut the door. “We’re ready to close in on this guy,” he said, “and this is what I want you to do. Tell him that you have a client who will be calling to order some prints.”

A day later, the bootlegger called back to tell me that my “client” had ordered quite a number of prints, that it seemed unusual, and that it would take a few days to complete the order. I was beginning to feel uneasy about the whole thing due to the volume of the order and the speed with which everything was taking place. I made it clear to the agent that both my name and where I worked absolutely had to be protected. If anyone at the lab or any of the other services I worked with, found out I was the informant, no one… NO ONE would ever trust me. And, more than likely, I’d be out of a job.

The agent assured me of complete confidentiality. “Relax,” he said. “We do this all the time. I give you my word, no one will know.”

A few days later, the agent instructed me to stay away from the lab the following day. Ironically, the bootlegger called while the agent was still in my office. He, too, was concerned by the large order, but said “if you say he’s okay, Jim. He’s okay.” All I could think of, from that moment on, was this man’s wife and kids from the picnic and what might happen if my name was revealed.

The following day, I remained in my office. Claiming I had a lot of paperwork to do, I sent one of my guys to Technicolor to pick up the prints. Later that afternoon, he returns to the office with a load of prints under his arm. “Man, you should have been there,” he tells me. “There were F.B.I. guys all over the place! And you should have seen it when [the bootlegger] was led away in cuffs.”

Even though I gave one of the great reacting jobs in my life, whenever anyone approached me about the incident – and everyone was talking about it for weeks – the whole thing made me sick. Worse yet was the realization that I could never tell anyone for fear that I would be looked on as someone who would turn anyone in if I noticed the slightest indiscretion. At the time, I only shared the story with a friend who agreed.

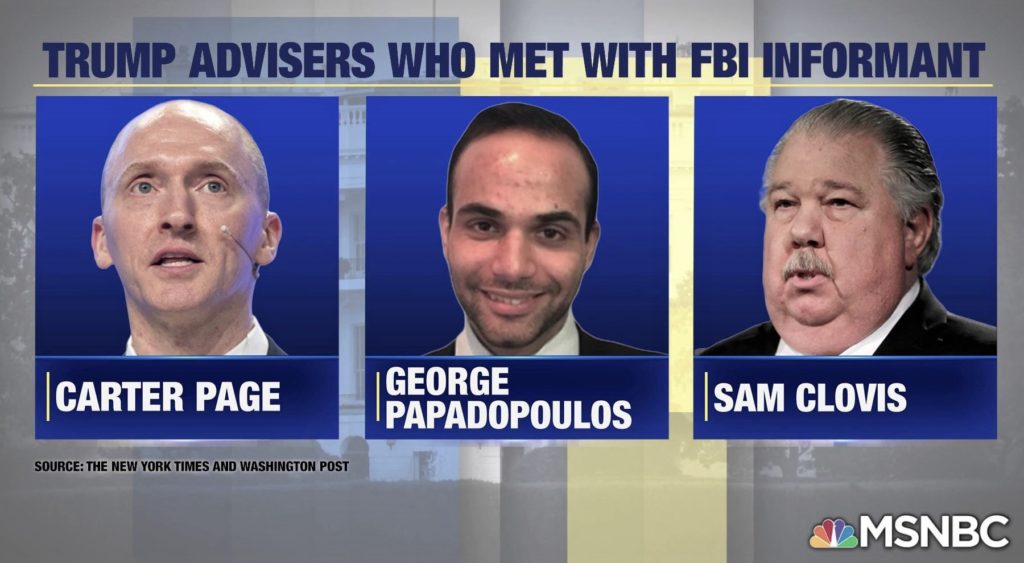

While criminal, this was a low-level investigation compared to what the current F.B.I. informant was involved in regarding Russia’s contact with Trump campaign aides Carter Page, George Papadopoulos and Sam Clovis. Yet, I know that with the release of his name his service to the F.B.I. is over and his credibility with any organization, much less his life, is at risk.

Our national security depends on individuals who are willing to look, listen and obtain information that is vital to our country’s safety. If an informant’s name is made known, who does U.S. intelligence turn to to get the information necessary to keep us safe, and how can they promise confidentiality to future informants?

Comments