Ethics is not about what we say or what we intend, it’s about what we do.

This is the heart of integrity – demonstrating a consistency between ethical principle and practice.

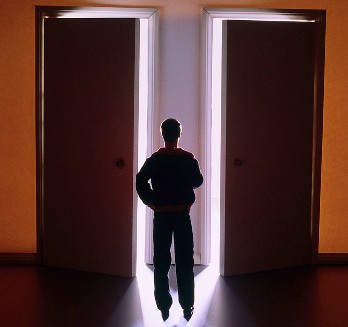

Who we are is never more clearly revealed than in the daily moments of our lives. How we respond to some of those moments reveals whether we stand up for our principles or rationalize our way around them. Sometimes, though, even the rationalizing moments can serve as an example to do better.

I like to include personal stories in these commentaries, especially those that clearly demonstrate that I will not be nominated for sainthood any time soon.

Sophomore English and I had drawn the most intimidating teacher on campus. Mr. Freeman was the tough-as-nails track coach and algebra teacher who could smell deceit. Blessed with the quickest hands in the business, if he even thought you were in the middle of a lie, you quickly felt a hard sting across your face that you’d never forget.

In algebra class, Freeman delighted in taunting anyone who was slow until you either solved the problem or had to tolerate him standing next to you as he explained every single step. He was this way with all school activities.

During a fundraiser, homeroom teachers would ask their students to sell raffle tickets. In Freeman’s class it was a requirement. Two days before Christmas break, he dropped two ticket books on everyone’s desk. When I respectfully explained that I would be leaving for California for the Holidays, Freeman just said, “I guess you’ll have to sell your tickets in the next two days.” When I politely pointed out that selling the tickets was an option not a requirement, he just glared at me, waiting for me to dig the hole deeper.

I explained that I would help in other ways, and that if he had difficulty with my decision, that perhaps we should both go talk to the principal – a reasonable guy – and discuss it.

More glaring.

I slowly walk up and place the ticket books on the edge of Freeman’s desk. He immediately jumps up, chair falling over – another intimidation tactic – and proceeds to tell me that I better pick up those tickets if I know what’s good for me.

I was shaking as I slowly return to my desk. Freeman said that we would discuss this after class, and everyone in the room knew what that meant.

The bell rings and everyone clears out of the room faster than the townsfolk in a B- Western when the bad guy comes to town.

More glaring then Freeman… slowly smiles. “Go on,” he says. “Go to California.”

Looking back on it now, I realize that it was my first real ‘moment of principle,’ where my integrity was put to the test on an issue of fairness.

For all my struggles with algebra that year, I remember squeaking by with a D+. Math was not my gift. English was.

The following year, due to some last minute changes, Freeman was assigned to teach my English literature class. “This can’tbe happening! Not two years in a row!” But the gods must’ve been smiling on me. The difference between algebra and literature came down to this: there was only one correct answer in algebra; English literature is all interpretation.

That difference worked in my favor as I spent the next three months “interpreting” rings around Freeman. On the rare occasion that he would challenge an answer, I would reiterate my line of reasoning, quoting any supportive material, then finish by pointing out that, of course, this was my interpretation.

It got to the point where Freeman would call on me to explain to others the various metaphors and meanings of stories, poems and plays. I think Freeman respected my opinion because he knew that I wasn’t trying to bluff him with bullshit. And I must say, I enjoyed this little taste of respect.

I wish I could say that I lived up to that respect.

One day, he called a pop-quiz. It represented all of five points toward our total grade, but it was Freeman’s way of keeping everyone on their toes in keeping up with the reading assignments.

This was not a problem for me, but the guy sitting across from me was. Mr. Bad News had made it clear, on more than one occasion, that anyone who comes from California was one step up from a cockroach. When Freeman announced that we would exchange papers with our neighbor, a hand reached across the aisle, grabbed mine, and said that we would not be switching papers. “Understand!?”

I had a quick decision to make: take a chance on getting caught cheating by Freeman or be assured of a reckoning with Bad News. We didn’t exchange papers, but I told my “neighbor” to allow for at least one incorrect answer so it wouldn’t look obvious.

After going over the answers, Freeman is calling the roll, asking everyone their grade. Bad News confidently yells out, “100%!”

“What!” Freeman says, as he leaps from his chair and begins to approach the two of us. “Who graded your paper?”

“Lichtman, sir.”

“Lichtman! Well, that’s different.” Without a pause, Freeman turns and heads back to his desk.

Although I felt bad about it at the time, I had rationalized to myself that it was just a five-point quiz. What difference would it possibly make?

A month later, after telling a few friends that I would be moving back to California at the end of the semester, Freeman, uncharacteristically announced it to the entire class along with one thing more: “Lichtman is the only one in this class who has stood up to me. He’s the only one with any real class.”

A five-point quiz, that’s what I traded my integrity for.

Comments