“Why is it so hard for a man to see clearly beyond the letter of the law?”

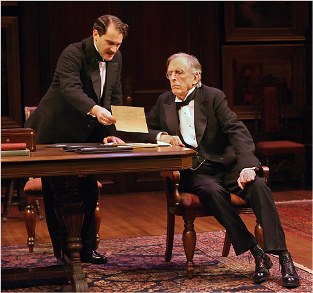

This deft piece of rationalization comes courtesy of Mr. Voysey, Sr. to his son, Edward, Jr. from a play by English dramatist Harley Granville Barker, edited by David Mamet.

“The Voysey Inheritance” is a 103-year-old morality play that gives proof to the notion that when it comes to fraud, the only things that change are the furniture and the clothes.

Edward Voysey, Sr. is the head of a large family “in society” as they say, in Victorian England. Among his spoiled children are the spoils of a very successful solicitor (old-world for what we call a banker or broker today). However, among the gilt-framed paintings of Gainsborough and Rubens is a sold gold swindle.

Edward, Jr. discovers that the road most traveled by his father has resulted in massive fraud for their clients by way of (mostly) failed stock speculations. The scheme has been passed down from grandfather to father and now the son.

“It’s your inheritance,” Senior explains.

After Voysey, Sr. dies, Junior is not only left holding the bag for the deception, but must explain to his siblings that their presumptive inheritance will be going to help repay the client-base that was defrauded.

The first-blush of outrage quickly turns conciliatory when the family discovers that if they follow Edward’s plan, they will all be penniless. When it is further explained that the only reason nothing has been uncovered has been due to a series of Ponzi-type schemes where the clients continued to be paid their annual revenue from different pockets. They all quickly sign-on to continue the scheme and when Edward, Jr. balks at the idea, they appeal to him to protect the family name. Over the next year he vows to make good on the losses.

Of course, what becomes very recognizable in all this are the comparisons to the subprime mess in the housing market.

According to Forbes writer Eric Petroff, the Cliff’s Notes version of the subprime crisis is this:

“The economy was at risk of a deep recession after the dotcom bubble burst in early 2000; this situation was compounded by the September 11 terrorist attacks that followed in 2001.

“In response, central banks around the world tried to stimulate the economy. They created capital liquidity through a reduction in interest rates. In turn, investors sought higher returns through riskier investments. Lenders took on greater risks too, and approved subprime mortgage loans to borrowers with poor credit. Consumer demand drove the housing bubble to all-time highs in the summer of 2005, which ultimately collapsed in August of 2006.

“The end result of these key events was increased foreclosure activity, large lenders and hedge funds declaring bankruptcy, and fears regarding further decreases in economic growth and consumer spending.

“It was the lenders who ultimately lent funds to people with poor credit and a high risk of default.

“When the central banks flooded the markets with capital liquidity, it not only lowered interest rates, it also broadly depressed risk premiums as investors sought riskier opportunities to bolster their investment returns. At the same time, lenders found themselves with ample capital to lend and, like investors, an increased willingness to undertake additional risk to increase their investment returns.

”In defense of the lenders, there was an increased demand for mortgages, and housing prices were increasing because interest rates had dropped substantially. At the time, lenders probably saw subprime mortgages as less of a risk than they really were: rates were low, the economy was healthy and people were making their payments.”

In other words, everyone was happy as long as the money flowed from one group to another, just like the Voysey scheme. And just like that scheme, at the end of the day, there was nothing substantial behind it.

The difference is that in the third act of this play, we all pay by either bailing out companies like Bear Stearns or by paying higher interest rates. The other uncomfortable difference is that we all share some responsibility by either looking the other way or trying to cash in.

Although legal, by the time the subprime crisis was realized for what it was, it was too late for meaningful corrections; a truly sad state of affairs especially for those families losing homes.

In ultimately going along with the family’s decision to continue the deception as he works to correct matters, Vosey, Jr. reflects, “It’s strange the number of people who believe you can do right by means which they know to be wrong.”

Look, I don’t pretend to have all the answers when it comes to the complicated series of policy decisions that led to the subprime crisis. But I do believe that each of us has a responsibility to see that clearer, ethical guidelines are not only put in place, but that corporate and political leadership follows through in making the right choices. Because at the end of the day, we all inherit the negative consequences.

Comments