“So act that your principle of action might safely be made a law for the whole world.” – Immanuel Kant

“Surely, I have made my meaning plain. I mean to avenge myself upon you, Admiral.” – Khan, a genetically enhanced superhuman who justifies his evil actions due to the death of his wife.

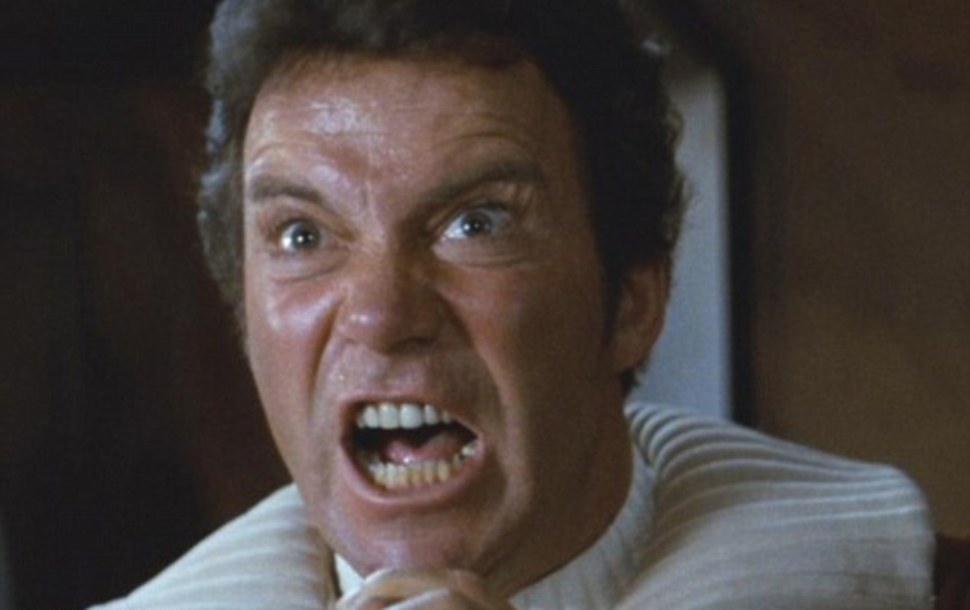

“KHAAANNNN!” – Kirk, frustrated that his nemesis has turned the tables on him.

Star date: 09081966: that’s the date that lives in the minds of “original” fans of the show that changed the face of several generations in both culture and technology.

Remember how “Bones” McCoy would make notes on an electronic tablet, or when Spock would call-up any and all information on his hand-held data recorder, or the time when Captain James T. Kirk would urgently punch his communicator and say, “Scotty, I need warp speed in three minutes or we’re all dead!” Creators of the iPad, and cell-phones owe a debt of gratitude to Trek creator Gene Roddenberry.

What made the original series work so well were the morality stories they told concerning issues of civil rights, sexism, war, and peace and how the characters dealt with them.

Star Trek and Philosophy: The Wrath of Kant, Edited by Kevin Decker and Jason Eberl (2008) examines major philosophical themes from a variety of philosophers. “Go Boldly, Yet Morally: Federation Ethics,” and “Multiple Enterprises: Metaphysical Conundrums from A to E,” offer the reader an interesting exploration into philosophers from Kant to Nietzsche. From Vulcan Stoicism to the Machiavellian business practices of the Ferengi, twenty-one professors write that there was a lot more philosophic theory behind the plot lines than perhaps we were aware of.

On the surface, Kant’s categorical imperatives seem ethically sound:

Rule of Universality – “Do only those acts which you are willing to allow to become universal standards of behavior applicable to all people including yourself.”

The Rule of Respect – all individuals are intrinsically important, and the well-being of each is a moral end in itself. One must never treat others simply as a means for your own gain.

Kant’s view is that individuals have an absolute duty to do the right thing no matter the situation or the consequences. Under Kant’s absolutist theory, one must never tell a lie because it would violate the principle of honesty. So, if the Nazis came knocking on your door asking where Anne Frank is hiding and you happen to know, you are duty-bound to tell the truth. Both the military and police would be forbidden to use any deceitful tactics, and, of course, Captain Kirk would be prohibited from using a similar strategy against the evil Khan.

“This is Admiral Kirk. We tried it once your way, Khan, are you game for a rematch?”

No response.

“Khan, I’m laughing at the ‘superior intellect.’ ”

In Dan Marinaccio’s 1995 book, All I Really Need to Know I Learned from Watching Star Trek, the author talks about how we can utilize the moral lessons from the Trek characters to advance and improve our lives. However, the latest entry into the Trek universe of books is The Ethics of Star Trek, written by Judith Barad and Ed Robertson.

“One reason why Star Trek has endured,” Barad and Robertson say, “is that most of the stories… are indeed moral fables.”

According to Publisher’s Weekly, “Barad, professor of philosophy at Indiana University, and Robertson, rely on episodes from the four Star Trek TV series, they travel through various universes of ethical theory… the authors offer useful and evenhanded introductions to the ethical theories of Aristotle, Epicurus and the Stoics, Kierkegaard, [and] Nietzsche…

“For instance, Plato argued that the four virtues of temperance, courage, wisdom and justice would be the hallmarks of the ideal Republic. Barad and Robertson contend that Spock and Kirk exhibit courage in an episode called “The Savage Curtain” when they fight off shadows of four of history’s most evil creatures to prove that good is mightier than evil. ‘The Original Series most clearly reflects Aristotelian virtue;’ the authors contend, Star Trek: The Next Generation exemplifies ‘the ethics of duty… Deep Space Nine, existentialism; and Voyager, Platonic virtue.’

“Their effort to popularize a difficult subject occasionally results in egregious misreading,” Publisher’s Weekly points out. “Nietzsche, for instance, did not base his philosophy on the concept that ‘might makes right,’ as he abhorred every system of subjugation and suggested that we are all continually engaged in overcoming such systems.”

As Kant (Immanuel) would say, “If I wish to quench my thirst, I must drink something. If I wish to acquire knowledge, I must learn”; or as Kirk would clarify to the Vulcan trainee, Saavik:

Saavik: Humor. It is a difficult concept. It is not logical.

Kirk: We learn by doing.

So, with that in mind, I will kick-back, enjoy a fascinating glass of Romulan ale, beam up an “original” episode, and drink in all the wisdom, humor, and altruism from Kirk, Spock, Scotty, Bones, Uhrua, Sulu and Checkov.

Live long and prosper.

Comments