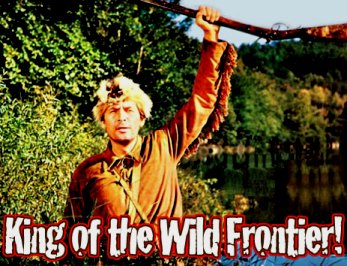

Like a few million other kids growing up in the fifties and sixties, I tuned in each week to watch the adventures of Davy, Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier, and yes I was wearing my official Davy Crockett coonskin cap.

Davy Crockett, Indian Fighter; Davy Crockett Goes to Congress; and Davy Crockett at the Alamo – I lapped ‘em allup each thrill-packed week on TV. As hokey as many of the scenes and dialog are today, as a kid, I came away with my first notions of honesty, fairness and integrity.

“There’s never been a folk hero quite like Davy Crockett,” reads the back panel on an old VHS tape. “And you’ll see why when you watch him ‘grin’ down a bear, battle an Indian chief in a tomahawk duel and fight for freedom at the Alamo.”

Originally produced in the 1950s, the show was long on folksy myth and snappy lines and short on length, just the way kids like ‘em. In fact, the Disney version condensed so much that ‘ol Davy goes from Indian Fighter to Congressman in about 15 minutes and the battle of the Alamo only lasts about 2 days!

It made no difference that I was watching a sanitized version of history. I was too caught up in the adventures of Fess Parker as Crockett and Buddy Ebsen as his affable sidekick Georgie Russel to care.

The most action-packed standouts for me remain Davy’s Indian tomahawk fight with Red Stick, the sharpshooting match with Big Foot and his introductory speech before Congress. “I’m half-horse, half-alligator and a little attached with snapping turtle. I’ve got the fastest horse, the prettiest sister, the surest rifle and the ugliest dog in Texas. My father can lick any man in Kentucky… and I can lick my father. I can hug a bear too close for comfort and eat any man alive opposed to Andy Jackson.”

However, the real David Crockett would have kicked the crap out of Fess Parker if they ever faced-off in a fight. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the historical Crockett “made a name for himself in the Creek War,” and served two terms in the Tennessee legislature before serving three in the U.S. House of Representatives. His “winning popularity” came about “through campaign speeches filled with yarns and homespun metaphors.”

The real Crockett stood before Congress on more than one occasion to take a stand on principle. “It is a precedent fraught with danger for the country, for when Congress once begins to stretch its power beyond the limits of the Constitution, there is no limit to it and no security for the people… the Constitution, to be worth anything, must be held sacred and rigidly observed in all its provisions.”

Although brought to Congress in support of President Andrew Jackson, “Crockett broke with the [the president] and the new Democratic Party over Crockett’s desire for preferential treatment of squatters occupying land in western Tennessee.

“The Whigs early courted and publicized Crockett in the hope of creating a popular ‘coonskin’ politician to offset Jackson. In 1834 Crockett was conducted on a triumphal speech-making tour of Whig strongholds in the East. From the many stories about him in books and newspapers, there grew the legend of an eccentric but shrewd ‘b’ar hunter’ and Indian fighter.”

Despite his reputation as a colorful storyteller, the historical Crockett was able to separate fact from fiction and his fierce opposition to President Jackson’s Indian Removal Act, led to the defeat of frontiersman from the House in 1834. “It was expected of me that I was to bow to the name of Andrew Jackson,” he said, “even at the expense of my conscience and judgment. Such a thing was new to me, and a total stranger to my principles.”

Davy Crockett was always willing to put his reputation, career and eventually his life on the line in defense of his principles. He left for Texas not long after leaving Congress, telling his colleagues on the hill, “You may all go to Hell, and I will go to Texas.”

Joining the fight for Texas Revolution, David Crockett frontiersman, Indian fighter, and U.S. Congressman made his final stand on principle when he was killed in the battle at the Alamo. His legacy contained more than a few exaggerated stories, but some practical wisdom we can all be reminded of:

We have the right as individuals to give away as much of our own money as we please in charity; but as members of Congress we have no right to appropriate a dollar of the public money.

I have always supported measures and principles and not men.

I would rather be politically dead than hypocritically immortalized.

“Always be sure you are right, then go ahead.”

Comments