Sometimes we get so caught up in the brush-fire of the moment that we forget about what’s really important – the people around us who contribute to our lives in special ways.

I’ve been lucky to not only have met but developed deep friendships with many people through my work; people who demonstrated, through moments in their lives, the courage, skill, responsibility and compassion that reveal who they are.

These are the people who inspire me; who remind me what’s important and why.

I will be sharing two such moments from Vietnam era thoracic surgeon John Baldwin’s life. This first story reveals his dedication as a young surgical intern. In an inside note of a John sent me, One Patient at a Time – A Medical Center at Work, author Milton Zisowitz documents a day in the life of a… “young intern [Baldwin], only three months out of medical school, whose courage and split-second thinking saved the life of a fifty-year-old lawyer in an emergency operation…”

“Even in a hospital,” Zisowitz writes, “equipped and alert for almost any emergency, a human life sometimes depends upon another human being. That human being, however, must be ready. And it is not enough that he be trained to do the things that must be done. He must also have the background, the tradition, and the character to do them – he must be a true physician. …

“Mr. Louis Sokol, a fifty-year-old lawyer, visited his family doctor complaining of vague pains in the chest. Since the diagnostic problem turned out to be somewhat difficult, he was referred to Dr. Eli Stonehill, the same private physician who supervises the second-year course in physical diagnosis. Physical examination including an electrocardiogram failed to reveal any heart disease, but the history and symptoms indicated the possibility of coronary insufficiency, or impaired flow of blood to the heart muscle, and the patient was urged to enter the hospital immediately for a complete check-up. The busy attorney insisted that he needed the weekend to finish an important brief, but at ten o’clock on Monday morning, he was admitted to a private room.

“For two days Dr. Stonehill observed his patient carefully and studied the many tests that were performed on him. Nothing seemed to be wrong, and since Mr. Sokol was altogether comfortable and the pains had disappeared, the physician planned to discharge him in a day or two on some simple medications and with the advice to slow down, watch his weight, and return to the office in a month for another examination.

“At 5:15 on Wednesday morning,” Zisowitz details, “the bell at the nurse’s station rang and the light showed that the call came from Room 308. No more than a minute elapsed before the nurse on night duty came to the lawyer’s assistance. Mr. Sokol was having a little pain and a mild coughing seizure, and she assured him that a doctor would see him as soon as possible. As she adjusted the pillow to make the patient more comfortable, he gasped deeply and stertorously, became pale and suddenly stopped breathing. The nurse lifted the bedside telephone to ask for help, but just then an intern assigned to the floor happened to look through the open door on his way to another room to check on a troublesome intravenous infusion.

“ ‘Get the cardiac tray,’ ordered the doctor as he tore open the patient’s pajamas and applied his stethoscope to the motionless chest.

“In the less than thirty seconds it took for the nurse to return with the sterile equipment it took for the nurse to return with the sterile equipment kept on every floor of the hospital for just this emergency, the physician, out of medical school only three months, had made his decision. He could detect no pulse either at the wrist or in the neck; he could hear no heartbeat. There is not time for consultation when the heart stops. Three, or at most four, minutes without oxygen will permanently damage the brain and leave the patient a vegetable rather than a human being if, indeed, he survives at all.

“Seizing a scalpel from the tray, the intern felt for the space between the fourth and fifth ribs and, with one firm slash, opened the lawyer’s chest and exposed his heart. The gaping would did not bleed, thus confirming the diagnosis of cardiac arrest and the urgency of immediate action. Thrusting his bare right hand into the opening, the physician grasped the heart and began alternately to compress and release the tough muscle at the rate of about seventy beats a minute. In the meantime, the nurse was forcing her own breath into Mr. Sokol’s lungs through a plastic tube she had inserted deep into his throat. Within minutes, other house officers summoned from their quarters arrived to help.

“The same house surgeon who had assisted with Mr. Hendricksen performed a tracheostomy, making a small incision directly into the windpipe. Through a tube in this hole, an assistant resident in anesthesiology began to administer oxygen from a machine while she attempted unsuccessfully to feel the pulse and measure the blood pressure. …

“Cardiac massage requires intense muscular concentration and considerable physical strength, and after ten minutes of incessant kneading, the intern was almost exhausted. The house surgeon took over without missing a beat, and between them the two men maintained the vital intermittent compression for almost half an hour before the patient began to show the first signs of returning to life. But the medical resident shook her head as she watched the tape coming out of the electrocardiograph. The heart was beginning to respond, but it was fibrillating – beating weakly and haphazardly, barely pumping blood. They couldn’t stop.

“The anesthesiologist was still unable to detect either pulse or blood pressure. Drugs injected directly into its muscle fibers somewhat strengthened the heart’s action but did not correct the dangerous arrhythmia. An electric defibrillator was brought down from the operating room, and every few minutes the cardiac massage was momentarily interrupted so that minute shocks could be delivered in an attempt to restore normal rhythm.

“Dr. Stonehill burst into the room a little before six o’clock. A few questions and a hasty glance assured him that the house officers were doing everything possible or his patient. Resting from his stint, the assistant resident in surgery had joined his medical colleague at the electrocardiograph. The anesthesiologist kept squeezing the oxygen bag with one hand while she kept the fingers of the other pressed against the lawyer’s wrist. The intern’s hand was hidden, but the sweat on his forehead and the rhythmic bulging of his arm muscles reflected the effort it takes to massage a heart.

” ‘Send for blood,’ Dr. Stonehill ordered. ‘If he comes out of this, he’ll need plenty to bring up the pressure and pull him through the rest of what he faces. And we’d better have a supply of penicillin too. There’s bound to be some infection in that wound.’

“Then there was tense silence, heightened by the gentle whoosh of the oxygen apparatus and the heavy breathing of the intern as he labored with the lawyer’s heart in his hand. Dr. Stonehill sank heavily into a chair, a thumb and forefinger tightly pressed against his eyes.

“Suddenly the anesthesiologist and the woman doctor glanced at each other in the same instant and whispered almost simultaneously, ‘I feel a pulse!’ ‘There’s a change in rhythm!’

“ ‘Keeping pumping!’ cried Dr. Stonehill as he sprang to his feet and peered intently at the tape rolling out of the electrocardiograph. He studied the strip for well over a minute and then his eyes lighted up. ‘Normal sinus rhythm. Now he’s got a fighting chance.’

“The internist was now reasonably sure that his patient’s heart could take over for itself and he ordered the cardiac massage stopped. The house surgeon closed and dressed the wound while the nurse adjusted the bottles that were now dripping blood, medications, and food into an arm vein. While a technician raised an oxygen tent over the bed, the anesthesiologist checked the tracheostomy tube and turned off her machine. Finally, Dr. Stonehill pulled his stethoscope away from his ears, folded it with deliberate movements, and tucked it into a hip pocket.

“ ‘Where is that young fellow?’ he asked, slowly looking around the room for the intern.

“There was no answer.

“ ‘I think I know,’ he said.

“He went downstairs and sat quietly at the rear of the chapel. When the intern raised his head and turned to leave, Dr. Stonehill held out his hand and said, ‘I’m proud of you. You were just a kid when I saw you enter medical college four years ago. Now, you’re a doctor. I often wonder – how does it happen?’ ”

The name of this remarkable intern, just three months out of medical school, was left out of the story. I’d like to think that this was the writer’s intention. An anonymous everyman, much like police, fire, military, bystanders, and neighbors we read about in news reports of similar heroic actions.

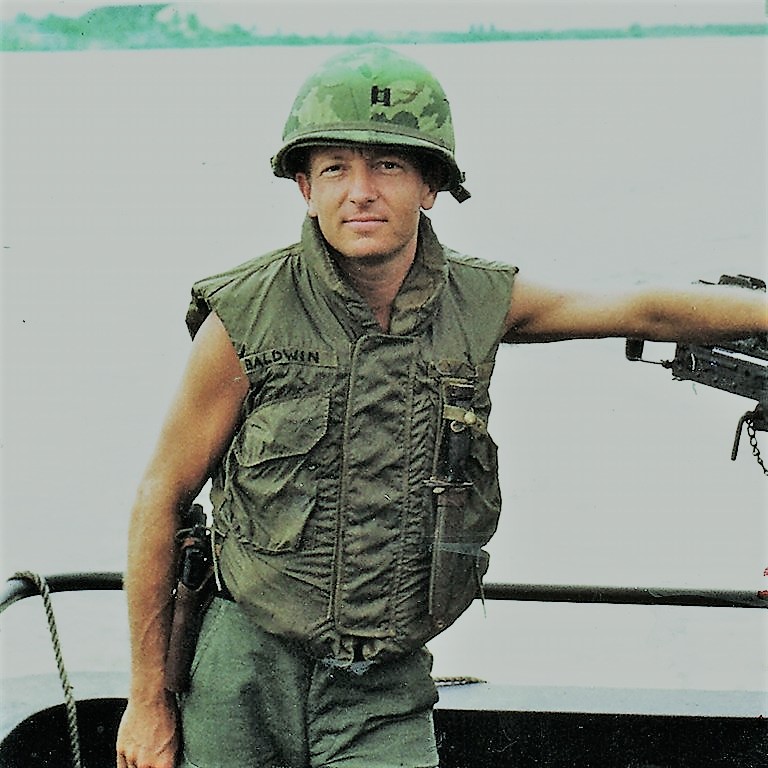

This doctor would later go on to Vietnam and save the lives of countless soldiers on the battlefield.

His name is John N. Baldwin who went on as chief of thoracic surgery in Vietnam. In a copy of the book he gave me, John added these few remarks: “[This book] documents a day in my internship, which was in internal medicine; and the event, in the summer of 1959 which was God-given, was to take me into cardiac surgery the following year.

“The only discrepancy in the text,” John adds, “is the fact that I used my pocket Boy Scout knife, not a ‘cardiac tray.’ ”

Amazing!

Comments