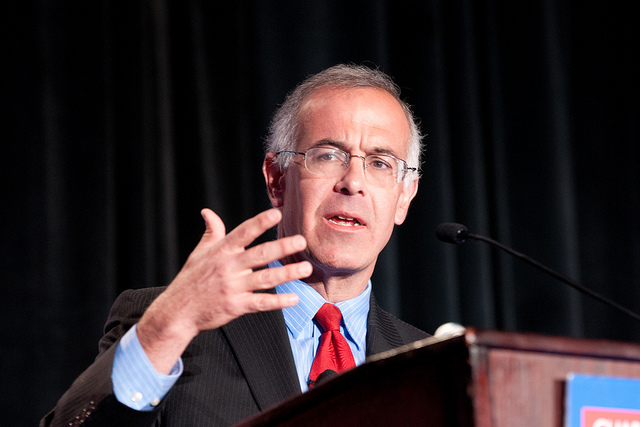

Why do I like New York Times columnist David Brooks?

Simple. Much of the time, I write about the tree. Brooks writes about the landscape. I tend to look at the brush fire that’s threatening the tree. He focuses on how America’s inherent strength can overcome the fires of our discord.

One thing about commentaries in The Times is that they frequently carry a different online title from their print edition. Last Sunday, Brooks’s column was “Healing the American Soul,” the online version: “How to Create a Society that Prizes Decency.”

Both titles carry their intended impact. Decency is a vital part of America’s soul.

Brooks begins with a question we all should be asking ourselves: “The pain in America resides in places deeper than economic policies can reach. So how can we create a society in which it is easier to be decent to one another?”

“To answer that question,” Brooks writes, “I returned to Howard Thurman’s magnificent 1949 book, ‘Jesus and the Disinherited.’ Thurman, a Black theologian, was a contemporary of Martin Luther King Sr., at Morehouse and had a strong influence on the activism of his son, Martin Luther King Jr.

“In the book, Thurman asks a series of profound questions: How is it possible for the disinherited and the oppressed to live pushed against the wall without losing their humanity? More broadly, how is it possible to strengthen the spiritual and social foundation of society so that people will recognize one another’s full dignity amid the normal tussles of life? These are germane questions today when so many — on the left and right — feel that society has pushed them against the wall.”

“In a passage that anticipates the rise of Donald Trump, Thurman notes the awful power of the demagogue who says to the alienated youth: ‘No one loves you — I love you; no one will give you work — I will give you work; no one wants you — I want you.’ In another passage that anticipates the current agony in Gaza: ‘The doom of the children is the greatest tragedy of the disinherited.’”

I cannot think of a more straightforward explanation of Trump’s cult-like appeal to those who regard him as the only one who can restore wholeness to their lives.

“It is natural, Thurman writes, for people who are disinherited to feel fear and hatred toward their oppressors. It is natural to want to lie to those who dominate you in order to protect yourself. But, he continues, these are self-destructive responses.

“He writes, ‘Jesus rejected hatred because he saw that hatred meant death to the mind, death to the spirit, death to communion with his father.’ When you try to deceive someone else, even for your own protection, you end up becoming a deceiver deep in your nature. You end up losing the ability to make moral distinctions.”

Sadly, this is where much of the country finds itself today: morally jumbled.

I see three groups in today’s political and cultural topography: those who believe that Trump is the only answer, those who think that Trump is self-guided and provides no moral leadership, and the seemingly amoral tens of thousands–maybe millions–who are content to sit on the sidelines and watch. The last group has morals. They’ve just been so bludgeoned by the chaos, name-calling, lies, and disinformation that has permeated our politics and culture that they have chosen to disengage from the democratic process altogether. It feels like an unending cage match between right and wrong, and right appears to be running out of steam.

So, how do we change from where we are to where we want to be as a country?

“To be a good citizen,” Brooks writes, “it is necessary to be warmhearted, but it is also necessary to master the disciplines, methods, and techniques required to live well together: how to listen well, how to ask for and offer forgiveness, how not to misunderstand one another, how to converse in a way that reduces inequalities of respect. In a society with so much loneliness and distrust, we are failing at these social and moral disciplines.”

Brooks’s clarity is essential for change, but the key adjective is discipline. To regain our moral compass, we need to look at each other as Americans, not adversaries, listen more than we speak, and respect rather than name-call. If we can commit to moral discipline as fervently as we do to individuals, maybe we can learn to trust one another again.

Comments