Colman McCarthy is always a supportive friend but he’s much more.

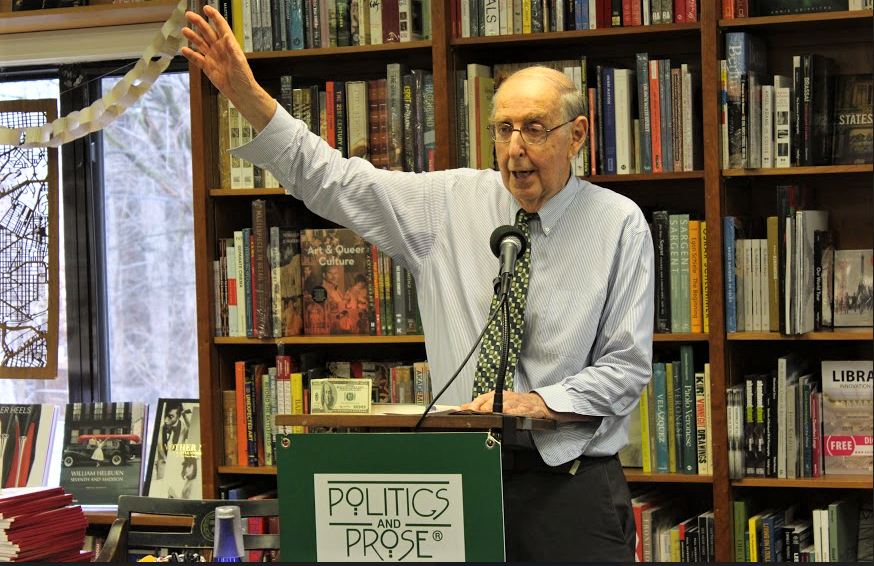

From the pulpit: Colman McCarthy preaching the gospel of peace, justice and humanity.

The former Washington Post columnist retired to start The Center for Teaching Peace, a radical little group that has the audacity to believe that “unless we teach our children peace, someone else will teach them violence.”

Among his advisory board: former Senators Ron Wyden and Mark Hatfield, Arun Gandhi (yes, that Gandhi), Nobel Peace Laureate Adolfo Perez Esquivel, former Peace Corps founder Sargent Shriver… and that’s only twenty percent of his board!

Oh, and along the way, McCarthy received the El-Hibri Peace Education Prize.

Over the holidays, I received a warm handwritten letter from McCarthy, (one of the few who still believes in the sincerity of putting pen in hand). Among the things he recently observed on my website was Ethical Hero of the Month, Dorothy Day. It comes as little surprise to me that he knew Day!

“I came to know her,” McCarthy writes, “both at her home in Manhattan’s lower east where she ran her house of hospitality, as she called it. Much better than homeless shelter.”

His letter included a piece he wrote that first appeared in The Nation (Dec. 1, 1997) on the significance of Day’s life’s work. It should inspire all of us to higher purpose.

“Half an hour before dawn in the kitchen at Dorothy Day House in Duluth, Steve O’Neil is bringing the kettle of vegetable soup to a boil. It will be part of the daily lunch for homeless people and families who have been given hospitality here for much of the past ten years. On the wall of the living room is a poster with the words of Archbishop Helder Camara of Brazil: ‘When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.’

“O’Neil, 47, Chicago-born and versed in the arts of neighborhood organizing as taught by Saul Alinsky, is one of a dozen members of the Catholic Worker community in Duluth. All are tied philosophically to a tradition based on the purity of early Christianity, when nonviolence, communal sharing of possessions, resistance to coercive state power and the Sermon on the Mount – what Dorothy Day called ‘the manifesto of the [Catholic Worker] movement’ – were signs of faith.

“Day, who was born just over a century ago, on November 8, 1897, co-founded Catholic Worker in 1933. A convert who had had a child out of wedlock, an abortion and a common-law marriage, she became a pacifist and philosophical anarchist who defied coercive state power but not Catholic theology. John Cardinal O’Connor, Archbishop of New York, will take steps to propose her for sainthood, although Day often said, ‘Don’t turn me into a saint.’ Her work, she insisted, was not beyond the reach of ordinary folk.

“For nearly sixty-five years the Catholic Worker, which has many Catholic members but no organizational ties to the Church of Rome, has been the soul of the American left. No other grouping – not the ACLU, the NAACP or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference – has had as many people involved personally in the work of war resistance, service, nonviolence and restorative justice.

“When I went to Dorothy Day’s funeral in 1980, much of the talk was about whether the Worker would keep on. It was an organism, after all, not an organization. It has never had a central headquarters, bylaws, annual conventions or a board. It takes no foundation or government lucre and rejects the advantages of being a nonprofit corporation. The prevailing opinion was the faith-based one Dorothy Day offered in her final years: ‘If God wants it to survive, it will.’

“The answer seems clear: In 1988, 106 Catholic Worker houses were operating in thirty-one states, Canada and overseas. In 1996, the Catholic Worker – the eight-page newspaper published in New York and selling for a penny a copy, the same price as in 1933 – listed 150 houses in thirty-five states, Canada and elsewhere.

“In my travels over the years, I’ve come to know two dozen or so of the communities. Instead of going to church, I hang out at Catholic Worker houses: Better to see a sermon than to hear one,” McCarthy points out.

“They’re also places to get a no-bunk read on local politics. For intellectual stimulation, and to keep their blood boiling, most Catholic Workers are pacifists who persist in getting arrested or jailed for what Jesuit John Dear calls ‘the sacrament of civil disobedience.’

“On the notion that altruism and idealism are contagious, I regularly expose my students to the Catholic Worker. What better way to head off a few of my Georgetown law students from going into corporate law than to have them read Dorothy Day? I relish taken them to a Catholic Worker house where they learn that laws represent the failure of love.”

Colman, I’m not only awed by your own work but the noble people you have hung out with. I can’t wait to hear about your adventures on FDR’s kitchen cabinet!

Comments