A favorite childhood memory of mine is sitting around the dining table – mom, pop, brother and me – rolling the dice and hoping to make my fortune by buying and building on several properties.

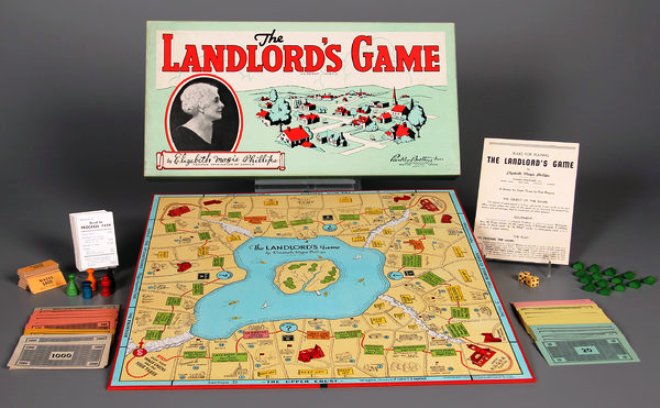

Ah, yes, we all enjoyed a good time with The Landlord’s Game.

The what?

In a new book, out last month, entitled The Monopolists: Obsession, Fury, and the Scandal Behind the World’s Favorite Board Game, author Mary Pilon sets the record straight about exactly who invented the incredibly popular and extraordinarily successful board game, Monopoly.

“The tale,” The New York Times adapts from Pilon’s book (Feb. 13), has been “repeated for decades and often tucked into the game’s box along with the Community Chest and Chance cards, was that an unemployed man named Charles Darrow dreamed up Monopoly in the 1930s. He sold it and became a millionaire, his inventiveness saving him — and Parker Brothers, the beloved New England board game maker — from the brink of destruction.”

While Hasbro, the owner of game-maker Parker Brothers since 1991, is celebrating the 80th anniversary of Monopoly, Pilon has been busy researching the real story behind the creation of the game and the woman who could be construed as being cheated out of her rightful claim to the property.

“Unlike most women of her era, [Elizabeth Magie] supported herself and didn’t marry until the advanced age of 44. In addition to working as a stenographer and a secretary, she wrote poetry and short stories and did comedic routines onstage. She also spent her leisure time creating a board game that was an expression of her strongly held political beliefs.

“Magie filed a legal claim for her Landlord’s Game in 1903, more than three decades before Parker Brothers began manufacturing Monopoly. She actually designed the game as a protest against the big monopolists of her time — people like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller.

“She created two sets of rules for her game,” Pilon writes, “an anti-monopolist set in which all were rewarded when wealth was created, and a monopolist set in which the goal was to create monopolies and crush opponents. Her dualistic approach was a teaching tool meant to demonstrate that the first set of rules was morally superior.”

(Clearly, Magie didn’t appreciate the fact that people who have nothing would prefer money to morals.)

“And yet it was the monopolist version of the game that caught on, with Darrow claiming a version of it as his own and selling it to Parker Brothers. While Darrow made millions and struck an agreement that ensured he would receive royalties, Magie’s income for her creation was reported to be a mere $500.

“Amid the press surrounding Darrow and the nationwide Monopoly craze,” Pilon continues, “Magie lashed out. In 1936 interviews with The Washington Post and The Evening Star she expressed anger at Darrow’s appropriation of her idea. Then elderly, her gray hair tied back in a bun, she hoisted her own game boards before a photographer’s lens to prove that she was the game’s true creator.

“ ‘Probably, if one counts lawyer’s, printer’s and Patent Office fees used up in developing it,’ The Evening Star said, ‘the game has cost her more than she made from it.’

“In 1948, Magie died in relative obscurity, a widow without children. Neither her headstone nor her obituary mentions her role in the creation of Monopoly.”

However, as Pilon writes, it is Elizabeth Magie’s back story that makes this a particularly interesting account.

“[Magie was Born] in 1866, the year after the Civil War ended and Abraham Lincoln was assassinated. Her father, James Magie, was a newspaper publisher and an abolitionist who accompanied Lincoln as he traveled around Illinois in the late 1850s debating politics with Stephen Douglas. …

“Because of her father’s part ownership of The Canton Register, Elizabeth was exposed to journalism at an early age. She also watched and listened as, shortly after the Civil War, her father clerked in the Illinois legislature and ran for office on an anti-monopoly ticket — an election that he lost.

“The seeds of the Monopoly game were planted when James Magie shared with his daughter a copy of Henry George’s best-selling book, ‘Progress and Poverty,’ written in 1879.

“As an anti-monopolist, James Magie drew from the theories of George, a charismatic politician and economist who believed that individuals should own 100 percent of what they made or created, but that everything found in nature, particularly land, should belong to everyone. George was a proponent of the ‘land value tax,’ also known as the ‘single tax.’ The general idea was to tax land, and only land, shifting the tax burden to wealthy landlords. His message resonated with many Americans in the late 1800s, when poverty and squalor were on full display in the country’s urban centers.

“The anti-monopoly movement also served as a staging area for women’s rights advocates, attracting followers like James and Elizabeth Magie.

“In the early 1880s, Elizabeth Magie worked as a stenographer. At the time, stenography was a growing profession, one that opened up to women as the Civil War removed many men from the work force. …

“She also spent her time drawing and redrawing, thinking and rethinking the game that she wanted to be based on the theories of George, who died in 1897. When she applied for a patent for her game in 1903, Magie was in her 30s. She represented the less than 1 percent of all patent applicants at the time who were women. …

“It hadn’t been easy. Several years after she obtained the patent for her game, and finding it difficult to support herself on the $10 a week she was earning as a stenographer, Magie staged an audacious stunt mocking marriage as the only option for women; it made national headlines. Purchasing an advertisement, she offered herself for sale as a ‘young woman American slave’ to the highest bidder. Her ad said that she was ‘not beautiful, but very attractive,’ and that she had ‘features full of character and strength, yet truly feminine.’

“The ad quickly became the subject of news stories and gossip columns in newspapers around the country. The goal of the stunt, Magie told reporters, was to make a statement about the dismal position of women. ‘We are not machines,’ Magie said. ‘Girls have minds, desires, hopes and ambition.’ …

“Magie’s game featured a path that allowed players to circle the board, in contrast to the linear-path design used by many games at the time. In one corner were the Poor House and the Public Park, and across the board was the Jail. Another corner contained an image of the globe and a homage to Henry George: ‘Labor Upon Mother Earth Produces Wages.’ Also included on the board were three words that have endured for more than a century after Lizzie [as friends called her] scrawled them there: ‘Go to Jail.’

“ ‘It is a practical demonstration of the present system of land-grabbing with all its usual outcomes and consequences,’ Magie said of her game in a 1902 issue of The Single Tax Review. ‘It might well have been called the Game of Life, as it contains all the elements of success and failure in the real world, and the object is the same as the human race in general seem to have, i.e., the accumulation of wealth.’

“On some level, Lizzie understood that the game provided a context — it was just a game, after all — in which players could lash out at friends and family in a way that they often couldn’t in daily life. She understood the power of drama and the potency of assuming roles outside of one’s everyday identity. Her game spread, becoming a folk favorite among left-wing intellectuals, particularly in the Northeast. It was played at several college campuses, including what was then called the Wharton School of Finance and Economy, Harvard University and Columbia University. Quakers who had established a community in Atlantic City embraced the game and added their neighborhood properties to the board.

“It was a version of this game that Charles Darrow was taught by a friend, played and eventually sold to Parker Brothers. The version of that game had the core of Magie’s game, but also modifications added by the Quakers to make the game easier to play. In addition to properties named after Atlantic City streets, fixed prices were added to the board. In its efforts to seize total control of Monopoly and other related games, the company struck a deal with Magie to purchase her Landlord’s Game patent and two more of her game ideas not long after it made its deal with Darrow.

“In a letter to George Parker, Magie expressed high hopes for the future of her Landlord’s Game at Parker Brothers and the prospect of having two more games published with the company. Yet there’s no evidence that Parker Brothers shared this optimism, nor could the company — or Darrow — have known that Monopoly wouldn’t be a mere hit, but a perennial best seller for generations.” …

“Magie’s identity as Monopoly’s inventor was uncovered by accident. In 1973, Ralph Anspach, an economics professor, began a decade-long legal battle against Parker Brothers over the creation of his Anti-Monopoly game. In researching his case, he uncovered Magie’s patents and Monopoly’s folk-game roots. He became consumed with telling the truth of what he calls ‘the Monopoly lie.’

“In a deposition for that case, Robert Barton, the Parker Brothers president who oversaw the Monopoly deal, called Magie’s game ‘completely worthless’ and said that Parker Brothers had published a small run of her games ‘merely to make her happy.’

“Mr. Anspach’s legal battle lasted a decade and ended at the Supreme Court. But he won the right to produce his Anti-Monopoly games, and his research into Magie and the game’s origins was confirmed.

“Roughly 40 years have passed since the truth about Monopoly began to appear publicly, yet the Darrow myth persists as an inspirational parable of American innovation. It’s hard not to wonder how many other buried histories are still out there — stories belonging to lost Lizzie Magies who quietly chip away at creating pieces of the world, their contributions so seamless that few of us ever stop to think about the person or people behind the idea.”

Comments