John Wayne famously said that “Courage is being scared to death and saddling up anyway.”

Time magazine’s current (July 21) cover story offers lessons in leadership by South African leader Nelson Mandela. Managing editor Richard Stengel tells a story that illustrates one characteristic that distinguishes Mandela, the leader.

“In 1994, during the presidential election campaign, Mandela got on a tiny propeller plane to fly down to the killing fields of Natal and give a speech to his Zulu supporters… When the plane was 20 minutes from landing, one its engines failed. Some on the plane began to panic. The only thing that calmed them was looking at Mandela, who quietly read his newspaper as if he were a commuter on his morning train to the office. The airport prepared for an emergency landing, and the pilot managed to land the plane safely. When Mandela and I got in the backseat of his bulletproof BMW that would take us to the rally, he turned to me and said, ‘Man, I was terrified up there!’

“I can’t pretend that I’m brave,” Mandela said, “[But as a leader] you must put up a front.”

“The act of appearing fearless,” Stengel points out, “inspires others. He knew that he was a model for others, and that gave him the strength to triumph over his own fear.”

We’ve all heard stories of courage in one form or other usually detailing events of some local hero who, without concern for his or her own safety, rescued one or more individuals from sure tragedy.

But there’s another kind of courage.

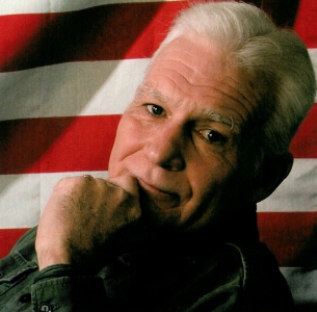

Moral courage requires us to step outside our own concerns and look at the larger picture. Former Marine Captain Dale Dye eloquently detailed the distinction between physical and moral courage for my book, “What Do You Stand For?”

“I would say a hero has two basic qualities: a selfless devotion to what’s right, whether that’s his duty or not, and the courage of his convictions. That’s simplistic but the classic example, of course, is the firemen and policemen who went into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Look that was a dangerous situation. Everybody knew it was a dangerous situation. But those folks had a higher devotion of doing something larger than themselves. It wasn’t just about a job at that point. Nobody is going to die for a job. They were outside themselves.

“We have a long history as human beings, regardless of nationality, of basing our ethos on specific heroes; people, who demonstrated a larger view of things, who think, feel and respond outside themselves. And thinking is sometimes a confusing term. I don’t think genuine heroes spend a lot of time contemplating that issue. I think they instinctively feel it as – this is right. And if you were to press them, in many cases, they probably couldn’t tell you why other than some vague notion. And that’s okay. It’s not necessary that our heroes be massive intellectuals. It’s only important that they do what needs doing in critical situations.

“But let’s take it out of a catastrophic event or combat situation. Let’s say you have a really good friend who’s involved in something that’s untoward. You can say to yourself, ‘Look, no skin off my nose. That’s what he wants to do. He’s a big boy and can do whatever he wants, and I’ll be here if he needs me.’

Well, that’s not courageous.

What’s courageous is you say, I’m more concerned about him than I am about me, so I’ll confront him. I’ll say, ‘Listen, you know this isn’t right. You know this is something that you shouldn’t be doing. Why are you doing it? If there’s a way I can help you, I will help you.’

“You may have known this guy for thirty-five, forty years. May be your best pal. And he says, ‘Well, screw you. You’re not my buddy. If you’re going to poke your nose inside my life; if you’re going to impose your morality on me, then you’re not a friend. You’re just some right-thinking wacko.’ And that’s very hurtful, but you stand your ground. You may lose the guy that you’ve loved for thirty-five years. And yet you have the courage of your convictions.”

It takes courage to stand on principle even at the risk of a job or a friendship. Dale Dye and Nelson Mandela recognize, first hand, the significance moral courage has in all our lives. We should recognize it, too.

Comments