A Special Counsel Report, hidden for 14 years, sheds light on the ethics of Ken Starr’s Office of Independent Counsel.

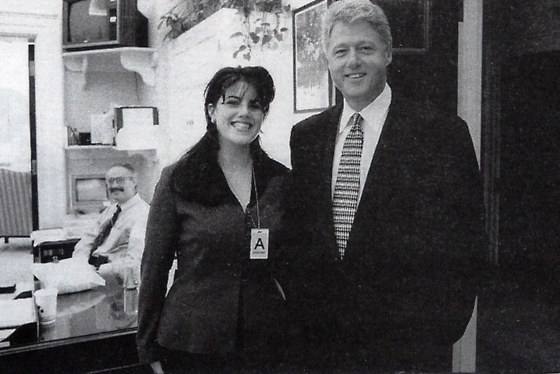

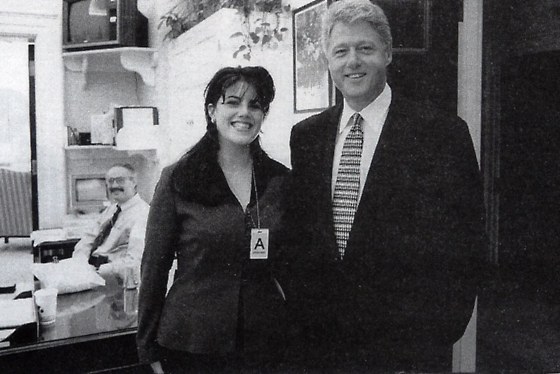

On January 16, 1998, Monica Lewinsky was rushing to meet Linda Tripp at the Pentagon City shopping mall across the Potomac in Arlington, Virginia. The two friends and former Pentagon co-workers were scheduled to have lunch in the food court at about 1:00 p.m. when two FBI agents approached Lewinsky. After showing their credentials, Tripp faded into the background.

According to a report, believed to be sealed by the court for almost 14 years, examining allegations of professional misconduct by the Office of Independent Counsel (OIC), one of the agents told Lewinsky that “she was in trouble and that she was the subject of a federal criminal investigation.”

Lewinsky responded: “Go fuck yourself.”

“There are OIC lawyers upstairs,” the agent explained, “who would tell you about the investigation.”

Lewinsky told the agent that he could speak to her attorney.

The agent cautioned that, “the offer to discuss her legal status was not being offered to her attorney, but to Lewinsky alone.”

The meeting was a set-up by Tripp, arranged by Ken Starr and the Office of Independent Counsel. Based on recorded conversations made by Tripp between herself and Lewinsky, Starr’s attorneys wanted to confront Lewinsky about her culpability in criminal activity related to an affidavit she filed in the Paula Jones civil lawsuit against President Bill Clinton. The agents advised Lewinsky that she was not under arrest, but would like her to accompany them to a room in the hotel to discuss the matter with Starr’s attorneys.

What took place during the “brace” of Monica Lewinsky has been reported before. What has not been available, however, is the account by Special Counsel which offers a far more comprehensive examination into what happened and why. After a 19-month Freedom of Information request, I obtained a copy of the 100-page report detailing the independent investigation conducted by former Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division Jo Ann Harris and her Co-counsel Mary Harkenrider.

The account is really an ethics report. In an interview, Harris made clear to me that while the actions taken by OIC lawyers may not have been found to constitute professional misconduct – according to the standards and definitions of the Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) – however, OIC’s lack of judgment at critical times, seriously compromised their decision making.

* *

In the fall of 1999, Robert Ray, then deputy to independent counsel Ken Starr, formally took over as head of the office after Starr resigned and returned to private practice. During the course of Starr’s six-year investigation of Clinton, several complaints were made regarding misconduct. Then-Attorney General Janet Reno dismissed all but those regarding OIC’s confrontation of Monica Lewinsky. On February 16, 2000, Ray enlisted Harris to conduct an investigation into those allegations.

Harris’s deal with Ray was simple: “I will be your OPR on this subject. We will follow the Department of Justice (DOJ) guidelines on the investigation, just as you are required to follow the guidelines on everything.” Harris added, “I was told not to disclose that I was working on the Lewinsky matter, and, in fact, it was never public record that I was appointed. My friends didn’t even know.”

Before beginning her work, Harris says that she and Ray had an understanding about her role and the way they would deal with any disagreement. As Ray explained to Harris, they would “put both reports out there and let the public decide.” Ray would later refuse to honor this understanding.

It was Ray’s position that Harris should be able to reach a conclusion regarding the Office of Independent Counsel’s conduct with Lewinsky from the papers OIC submitted to DOJ. However, Harris and Harkenrider concluded that because of the OIC papers’ “strongly adversarial substance and tone,” they “simply could not be relied upon as a basis for a fair determination of the facts involved.”

Harris maintains that she and Harkenrider were working under the assumption that the investigation and its findings would be made public. After submitting her report to Ray, however, something decidedly changed, surprising the seasoned justice official and leading me back to the archives as well as the U.S. Court of Appeals. Further research revealed a puzzling and convoluted subplot as to what happened to the report and why.

In the opening to their report, Harris and Harkenrider state, “Our task has been to investigate … allegations that OIC attorneys violated the Department’s regulation and other policies and rules bearing upon contact by federal prosecutors with persons represented by lawyers.”

At the time, Washington attorney Frank Carter was representing Lewinsky in the civil matter regarding Paula Jones. The distinction between the civil affidavit that Lewinsky made in the Jones case and the alleged criminal activity posited by the FBI agents who first approached her would become a key point later in the inquiry.

At the end of their ten-month investigation, Harris and Harkenrider found that “no lawyer involved in the confrontation with Monica Lewinsky committed professional misconduct.” Nevertheless, they conclude, one of Starr’s prosecutors “exercised poor judgment and made mistakes in his analysis, planning and execution of the approach to Lewinsky. We also note that the matter could have been handled better by all of OIC lawyers involved.

“The entire office knew that Frank Carter represented Lewinsky in the Paula Jones case.” The fact that she had legal counsel “should have set off alarms … as the OIC prepared to confront and try to ‘flip’ her. The President of the United States was the eventual target. Intense public scrutiny was inevitable; any misstep would exacerbate the criticism already directed at the office.”

In fact, the OIC prosecutor who led the “brace” of Lewinsky, was “… a Department lecturer on the issues involved, [and] specifically knew that there was a Department regulation and related DOJ policies guiding these types of contacts. He knew as well that those provisions were complicated, not self-evident, highly controversial and vulnerable to attack from many quarters. The confrontation of Monica Lewinsky demanded a high standard of care and sensitivity.”

Harris and Harkenrider found that the attorney who led the confrontation of Lewinsky “together with others, developed a strategy for discouraging Lewinsky from calling Carter cloaked as a generality: ‘If you call anyone, it may hurt your chances to help yourself,’ ” ultimately resulting in the attorney “offering a Hobson’s choice to Lewinsky, and then pushing her for an immediate answer … that choice was: ‘full immunity, or call the lawyer you desire,’ but not both.

“With Lewinsky, the OIC had a potentially explosive witness who seemed to be in the middle of committing several federal crimes. She could break open a real case against the President. But the timing of the investigation was being driven, in part, by outside forces and ultimately by a member of the press corps … Michael Isikoff of Newsweek magazine knew possibly more than the OIC lawyers did about the story and, later in the week, began breathing down their necks, threatening to contact the subjects before any law enforcement strategy could be implemented.

Context – The Office of Independent Counsel

“Prior to his appointment as Whitewater Independent Counsel in the summer of 1994, Kenneth W. Starr held a number of prestigious positions, including Solicitor General of the United States and Judge of the District of Columbia Court of Appeals. However, Starr had no prosecuting experience when he became Independent Counsel. His background and experience led to a management style and hiring strategy important to an understanding of the decisions made, how they were made and who made them in this case.

“Starr emphasizes that he tried to foster a collegial, non-hierarchical structure in the office, calling for the entire legal staff to meet on all important issues, and providing everyone the opportunity to express an opinion. The goal,” the report describes, “was to develop a decision by consensus.”

In an interview, Harris explained that Starr’s “process” was not what an experienced prosecutor should do. “I really believe that many of the people appointed [independent counsels] are ill-suited for the job. They don’t have a good sense of what a prosecutor does. They have their own self-righteous sense of quote ‘ethics,’ but they don’t understand this brown and gray world, and they don’t understand when they really have to say, ‘whoa!’

Harris and Harkenrider state, “Starr sought and hired … very strong prosecutors from Main Justice and the various United States Attorneys’ offices around the country. In addition, Starr hired prominent Washington lawyer and law professor Samuel Dash to serve as an ethics consultant, and encouraged lawyers to seek his advice on ethics matters.”

Dash had been the chief counsel for the Senate Watergate Committee investigating the 1972 break-in of Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate office complex in Washington, D.C. More importantly, he was considered the father of the Independent Counsel Statute. The law would prevent a sitting president from doing what President Richard Nixon did during Watergate: ordering the firing of Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox when Cox, supported by a ruling from U.S. District Judge John Sirica, compelled the president to hand over the secret White House tapes that would later lead to Nixon’s resignation.

However, “Dash says that he was hardly ever consulted by OIC prosecutors before action was taken, and was not consulted on [the Lewinsky matter].”

Context – Carter’s Representation of Lewinsky

“The 1998 Martindale-Hubbell biography of Francis Carter describes an experienced criminal and civil practitioner… who had served as a law clerk to the Chief Judge of the D.C. Superior Court and, from 1979-1985, was the Director of the Public Defender Service of the District of Columbia. …

“During Carter’s interviews with Lewinsky, she denied having a sexual relationship with the President and urged Carter to get her out of the deposition. … On several occasions, Carter warned Lewinsky about the perils of perjury and obstruction of justice.”

However, Ken Starr chose to believe a different narrative.

In one of many detailed footnotes, the investigators stress, “The way in which Lewinsky ended up with Carter caused some of the OIC staff to have suspicions that Carter was complicit in the scheme [to lie about the Clinton/Lewinsky relationship]. … in Starr’s words, it was their ‘instinct based upon experience with the Clinton people.’ … But, there was little evidentiary basis for concluding that Carter was involved in any scheme to commit perjury.”

Starr and many of his prosecutors were so wedded to their assumptions about “the Clinton people” that they ignored statements Lewinsky made to Tripp during their recorded conversations. For example, the report points out, “Lewinsky repeatedly made clear to Tripp that she had lied to Carter, stating that you cannot tell your own lawyer the truth if you want him to represent you.”

“[However] it does not appear there ever was a consensus among the OIC staff as to their view of Carter’s role. The [FBI] agents thought he was involved in the crime, as did Starr… [But] a Deputy Independent Counsel assigned to Little Rock at the time, consulting by telephone, acknowledged that they had information from Tripp that Lewinsky was misleading Carter and that there was no real evidence on him. [Another OIC attorney] says they had ‘no reason to believe whether Carter was straight or crooked,’ adding ‘we had never heard of Frank Carter.’ ”

A simple background check on Carter would have revealed much about the man and his reputation. Nonetheless, there was no indication to suggest that anyone at OIC ever attempted to find out who Carter was before approaching Lewinsky.

Thursday, January 15, 1998

In the meantime, Newsweek reporter Michael Isikoff was still pressing to run the Lewinsky story, a bombshell that as yet remained unknown to the public. (Two days later, the story would break on The Drudge Report, an on-line gossip site.)

“On Thursday morning … [OIC] began brainstorming how to approach Lewinsky. … the stronger personalities dominated the discussion … Others tell us there was a clash as to who was in charge and that [redacted] and [redacted] ‘glommed’ onto the case. [An FBI agent], noting that no one seemed to be in charge of the case, says that the OIC staff seemed still to be working on the jurisdictional issues before a meeting with [Deputy Attorney General Eric] Holder later that day… .”

At that meeting, Office of Independent Counsel made its case before Holder, believing they had related jurisdiction and would win DOJ’s approval for that position. Soon after the Chief of the DOJ Criminal Division’s Public Integrity Section called one of his deputies and asked him to go to OIC offices “ … to help DOJ determine the jurisdictional issue.” It was at the meeting between the attorney from DOJ and OIC where Starr’s lawyers were presented with alternatives but chose not to take them.

The Justice attorney “suggested that if OIC had concerns about Carter’s reliability or complicity, they should serve Lewinsky with a grand jury subpoena which would bring the question of Carter’s possible conflict before a court for determination. Such a strategy,” the report confirms, “would have placed Carter in a position that bound him not to reveal what was happening, or face allegations of obstruction of the grand jury.”

The same attorney “also raised DOJ’s regulation regarding contacting a person who has a lawyer… and told OIC lawyers that if he were they, he would not go forward without first seeking the guidance and protection provided by DOJ through the ‘Margolis’ procedure, a process established by the Department to help federal prosecutors evaluate issues involving the regulation proscribing contacts with represented people, on a case-by-case basis. By using the process, prosecutors not only received advice from Department experts, but obtained authority to proceed, thus providing protection from later charges of abuse.”

However, one OIC attorney responded that they “had looked at the issue of contacting Lewinsky without her lawyer and concluded it was okay. … Ultimately,” Harris and Harkenrider note, “Starr gave [the attorney] a letter to take back to DOJ. In it, he asserted once again that OIC had ‘related’ jurisdiction, but sought the Department’s opinion and a referral to OIC if the Department concluded to the contrary.”

With this letter, Starr now believed that the Office of Independent Counsel had the legal authority to confront Lewinsky.

That evening, a deputy OIC attorney walked by the door of the prosecutor charged with confronting Lewinsky. “I know you are the contacts guy. Are there any contacts problems here?”

His colleague sat back, and “after about 5-10 seconds said, ‘One, she’s not represented here; and two, it’s pre-indictment. No problem. [Carter is] her lawyer in a civil proceeding; his representation is to the affidavit in the civil case; whatever arrangement they have it is in the civil proceeding.’ ”

Thus, the lawyer regarded Carter “… just like any other person, not Lewinsky’s lawyer. This position, the investigators conclude, “colored all that occurred thereafter.

“Although all of the OIC lawyers involved had the obligation to ensure that they were proceeding ethically, they were relying on [this one attorney] to advise them on this issue. [Another lawyer] says that his attitude was ‘we’ve looked at it; we don’t need Department approval; we are our own office.’ ”

That evening, OIC arranged to have Tripp meet with Lewinsky at the Pentagon City shopping mall in Virginia. Tripp would guide Lewinsky to the FBI agents who would try to convince her to go with them to a room in the Ritz Carlton upstairs where she would be confronted with the evidence of her crimes and attempt to “flip” her.

“There was no script for the agents’ confrontation,” Harris and Harkenrider point out, “but the agents who were ‘gaming’ by themselves on Thursday night concluded that if Lewinsky asked for her lawyer, he would be contacted and the confrontation would be lawyer-to-lawyer thereafter.”

In an interview, Harris said, “the agents, who did the ‘brace’ on Lewinsky, were not happy with the process, or with the lawyers they were dealing with. [OIC] had no clear playbook in terms of what the agents ought to say, in terms of how they wanted to deal with the whole thing. The agents were just not part of the team.”

On the evening before the confrontation, three OIC lawyers met to discuss the plan. “It included offering Lewinsky a ‘cooperation made known’ deal, in which the quality of her cooperation would be taken into account … and made known to the sentencing judge.” If Lewinsky asked about contacting a lawyer, “ … they ‘would say that if she were to contact anyone, there was a risk she would be exposed and lose her chance to cooperate.’ No one seems to have taken any steps at this time to try to determine whether this was a proper means of discouraging her from contacting Carter, whether other means might be available, or whether encouraging her to forego contacting Carter was appropriate at all.”

Later that evening, the OIC attorney, selected as “the speaker,” began “to script out his presentation and circulated it to other lawyers in the office.”

Up Next: The Lewinsky Encounter

Comments

Leave a Comment

What a heroic investigation effort. You should get the Pulitzer. Bravo.