My opponent and I slowly walked to our lecterns.

While I was confident of my argument, I was nervous for the simple reason that this was my first debate and I had absolutely no idea how my audience would react, much less what kinds of questions would come in the second part. The topic was “Television in the Classroom” and I had the pro argument.

“Television can be an aide in teaching,” I began, rarely looking up from my notes. “The television screen has become the electronic blackboard, and as such is a new tool of learning with vast possibilities of shaping Democracy’s future,” (nice political touch).

At this point, I think I sound pretty good, due in no small part to my on-staff research department and speech writer… my mother. All of this magnificence was accomplished in only five gleaming paragraphs.

“Broadcasts and telecasts designed for home listening and viewing are programmed primarily for their entertainment value; however, there is an effort today to use television in the school.”

At this point, I decide to spontaneously add some emphasis.

“This type of education cannot… be found in the text book.” They loved it.

Moving in to the close: “What is an educational program? The late Dr. James R. Angell once said, ‘Any broadcast may be regarded as educational in purpose which attempts to increase knowledge and to stimulate thinking.”

The applause was immediate and impressive from my fellow 6th graders. Conveniently, I have no memory of my opponent’s words, (clearly, an early example of confirmation bias).

When it came to the Q&A portion, I was dancing all over any and all attacks from my opponent.

However, the reality is my moment in the sun had more to do with the simple fact that 100 percent of kids my age loved television. Therefore, an argument in favor of television in the classroom was a no-brainer.

And that, my fellow citizens, is how I won my first debate.

In all the talks I’ve given on ethics followed by an audience Q&A, no one ever interrupted or talked over me. In the two years that I have co-taught ethics in Concord New Hampshire’s Technical Institute, I was never interrupted. While I faced the challenge of engaging students, once engaged they were lively. On those occasions where a student interrupted another, I reminded them of the importance of respect and self-restraint.

“I want to hear what everyone has to say,” I told them, “but let’s do in a spirit of fairness and respect in allowing another to finish.”

They got it.

Of course, all of this brings me to the second debate between President Obama and Mitt Romney.

While many in the media, as well as his own party, loudly proclaimed that Obama was energized, engaged, even aggressive, as many in the GOP had felt about Romney, I was a little put off. Yes, I want to see each man call the other on misstatements of fact or policy changes. However, I was bothered by the number of interruptions by each one – something my own teachers would have never tolerated.

“C’mon, Jim,” you say, “politics is blood sport. The Continental Congress frequently degraded into Us vs. Themword battles. Interruptions became part of the narrative.”

In 1804, Alexander Hamilton feuded with Aaron Burr to the point that both men felt that the only way to ultimately settle their differences was “on the field of honor,” with pistols.

But that was 208 years ago!

Shouldn’t we be better than that?

In the second debate moderator Candy Crowley tried to corral both candidates several times, to no avail. According to those in the room, members of the audience gasped when Romney chided Obama for interrupting by saying: “You’ll get your chance in a moment. I’m still speaking.”

The usually respectful and patient former Massachusetts governor had turned into a pit bull in the debate cycle.

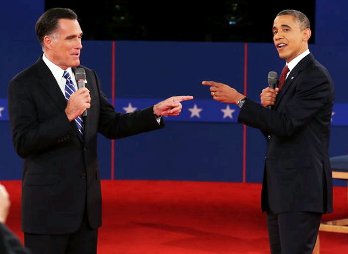

Early on, the words between the two got so testy that both men stood, practically in each other’s face pointing at one another.

C’mon, folks that’s not a debate, that’s the beginning of a cat fight from Desperate Housewives of Whatever-City-Comes-Next.

Inspite of their severe differences, and they were considerable, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas respected one another, and demonstrated that respect during their famous debates. Norman Corwin’s play, The Rivalry, captures the fierce rhetoric and cynical humor between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas. Throughout the course of seven debates in 1858, both men fought over state’s rights, slavery as well as the intent of the framers of the Constitution; and both acted with complete respect and restraint.

In reviewing tapes of the Kennedy-Nixon debates, both men clearly appeared not to like each other, but neither man interrupted, talked over or pointed a finger in the other’s face.

My hope for tonight’s final debate is that both Mr. Romney and President Obama will show us more self-restraint and a lot less in-your-face swagger. While both may express a passionate presence in their views, I hope that both will accept the other’s opposing views with grace and civility.

In making their arguments, no matter how fervent, they need to show us the best they can be. That’s what I’d like to see, and I think that’s what most Americans want, as well.

Comments