On Friday I wrote about the painful decision-making confronting physicians throughout the world who are not only facing a tsunami of coronavirus patients, but a shortage of critical supplies including ventilators, devices that provide air to those who are unable to breathe on their own.

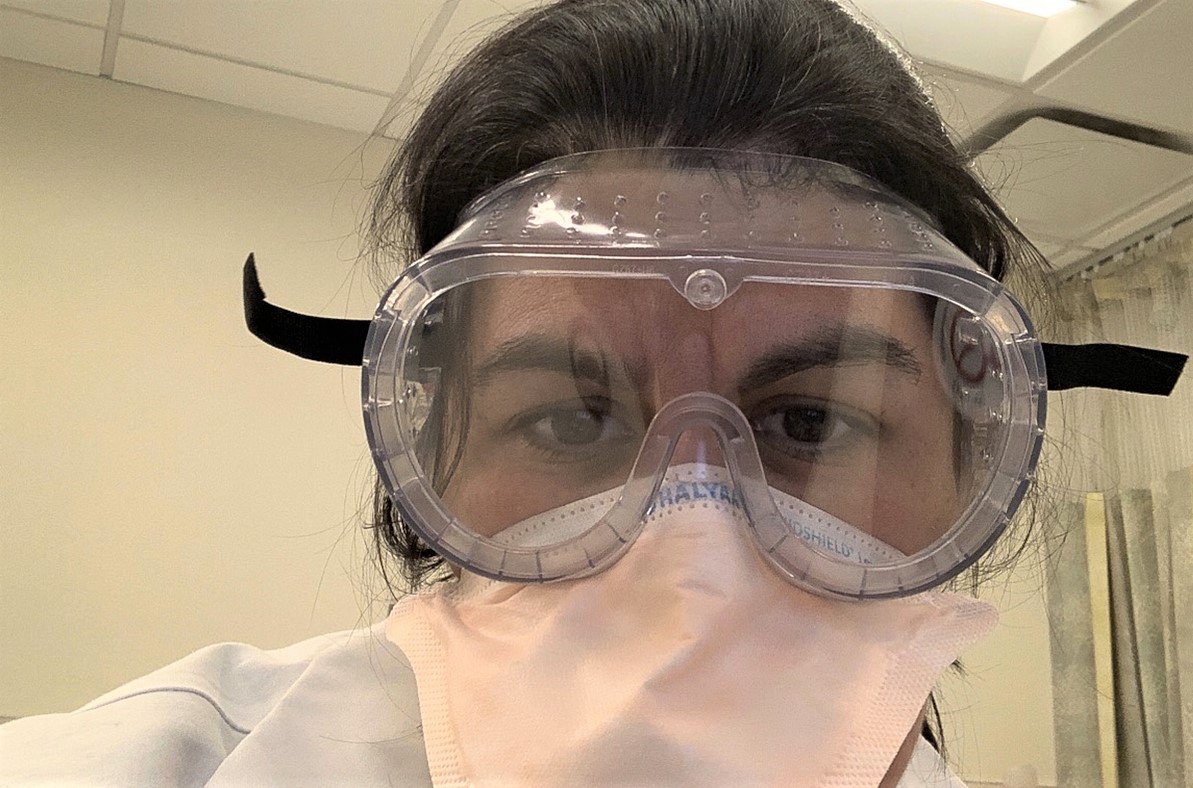

Dara Kass, an ER doctor and medical school professor at Columbia University in New York City, has taken special precautions to protect her family. Photo – Dara Kass

Ethical decision-making goes back as far as Chinese philosopher Confucius, who advised, “What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.”

Commonly known as The Golden Rule, the idea is that the best way to care for ourselves is to treat others with care. The downside to the rule, however, is there are often competing stakeholders, as is the case with the overwhelming number of COVID-19 patients. You cannot prioritize everyone.

German philosopher Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperatives place principles above all else. But what if you’re facing a choice between two ethical values, like caring and responsibility, which is exactly what physicians are facing now.

The most generally used decision-making is consequentialism which allows decision-makers to evaluate competing values. The drawback to this method, however, could lead to an end justifies the means scenario allowing non-ethical values, such as wealth and power to override universally accepted ethical values like honesty and responsibility.

Ethics teacher Michael Josephson developed a third ethical decision-making model that avoids the pitfalls of the previous three.

1. All decisions must take into account and reflect a concern for the interests and well-being of all stakeholders.

Josephson’s first step incorporates the Golden Rule: help others when you can; avoid harm, when you can.

2. Core ethical values – honesty, fairness, respect, responsibility, caring, citizenship – always take precedence over non-ethical values – wealth, power, etc.

The second step incorporates Kant’s absolute duty concept, whereby ethical values always take precedent over non-ethical values. However, ethical persons must choose to follow ethical values without rationalizing what may be in their own interest.

The final step pertains to the current issue.

3. It is ethically proper to violate an ethical value only when it is clearly necessary to advance another true ethical value which, according to the decision-maker’s conscience, will produce the greatest balance of good in the long run.

Like consequentialism, the third step calls on us to “triage” – to borrow a medical protocol used in emergencies – or prioritize among competing ethical values.

Returning to the dilemma: how do physicians choose who gets care and who, in critical circumstances, lives or dies?

Two words stand out: conscience, from the Josephson model; and judgment, from the physician’s code of ethics.

Conscience is our moral sense of what’s right and wrong. Wisdom involves applying experience and judgment about issues.

The physician’s code directs that he will treat his patient “according to my ability and judgment…”

However, in this circumstance, there’s another value that’s part of the physician’s code, obligation.

“I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations [responsibilities] to all my fellow human beings…”

On Saturday, I listened as New York Governor Andrew Cuomo explained that if patients have been on ventilators for an extended period, their chances of survival become less likely.

During the current crisis, where supplies and life-saving machines are in short supply, doctors should use their wisdom, conscience, and responsibility to society to weigh who receives vital care and who has the best chance of survival.

While doctors are faced with a critical healthcare crisis, a similar set of criteria can be used in organizations and corporations in deciding who will be laid-off and who is essential to the operation.

There are no easy or simple answers to any of these questions, however, Josephson further breaks down his decision-making into five steps of principled reasoning:

Clarify – determine precisely what must be decided. Develop a full range of alternatives.

Evaluate – if there are two or more competing values, evaluate the facts, clearly separating facts from beliefs or desires.

Decide – based on the best information available, make a judgment about what is or is not true and the consequences.

Implement – once a decision is made, develop a plan on how to implement the decision in a way that maximizes the benefits and minimizes the costs and risks.

Monitor and Modify – “an ethical decision-maker,” Josephson says, “should monitor the effects of decisions and be prepared and willing to revise a plan, or take a different course of action base on new information.”

Today, doctors are facing, perhaps the great crisis in ethics in healthcare they have ever faced, and there are many more questions and details that will challenge their decision-making. Nevertheless, the above criteria can help us sort through the many competing values and, based on the best information available, help us make the best decisions in the long run.

Comments

Leave a Comment

Thanks Jim for both parts on this ethically horrible and possible dilemma. Doctors have quite a task to do. Fortunately they are humans with emotions that help guide them from experience and knowledge. As you wrote, they must continue to “Monitor and Modify.”