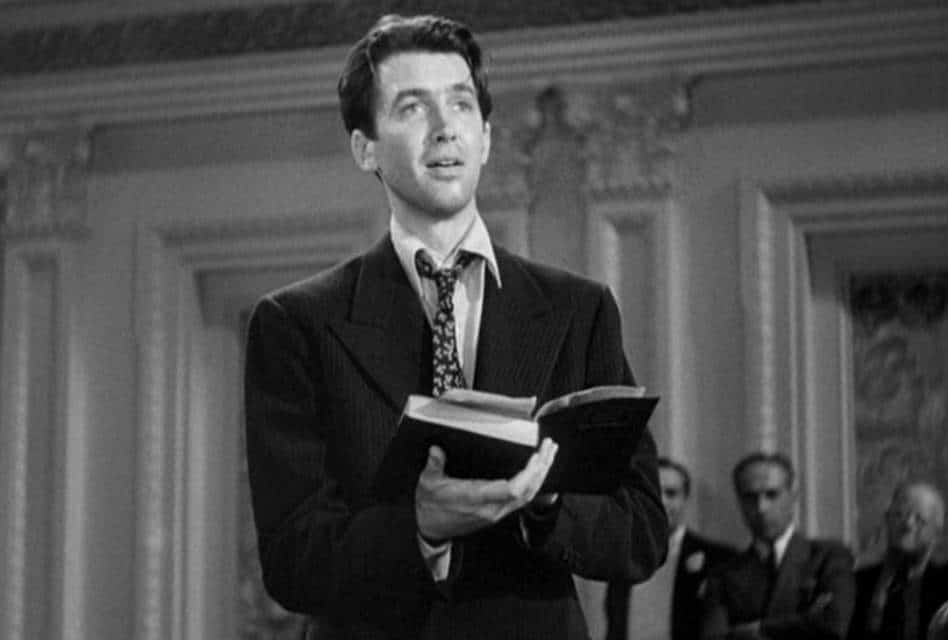

It’s been 60 years since Dr. King spoke to 250,000 supporters on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on a warm August afternoon in 1963.

King’s stirring words about character, however, were improvised not written. Standing close to the civil rights leader, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson whispered, “Tell ‘em about ‘the dream,’ Martin.”

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

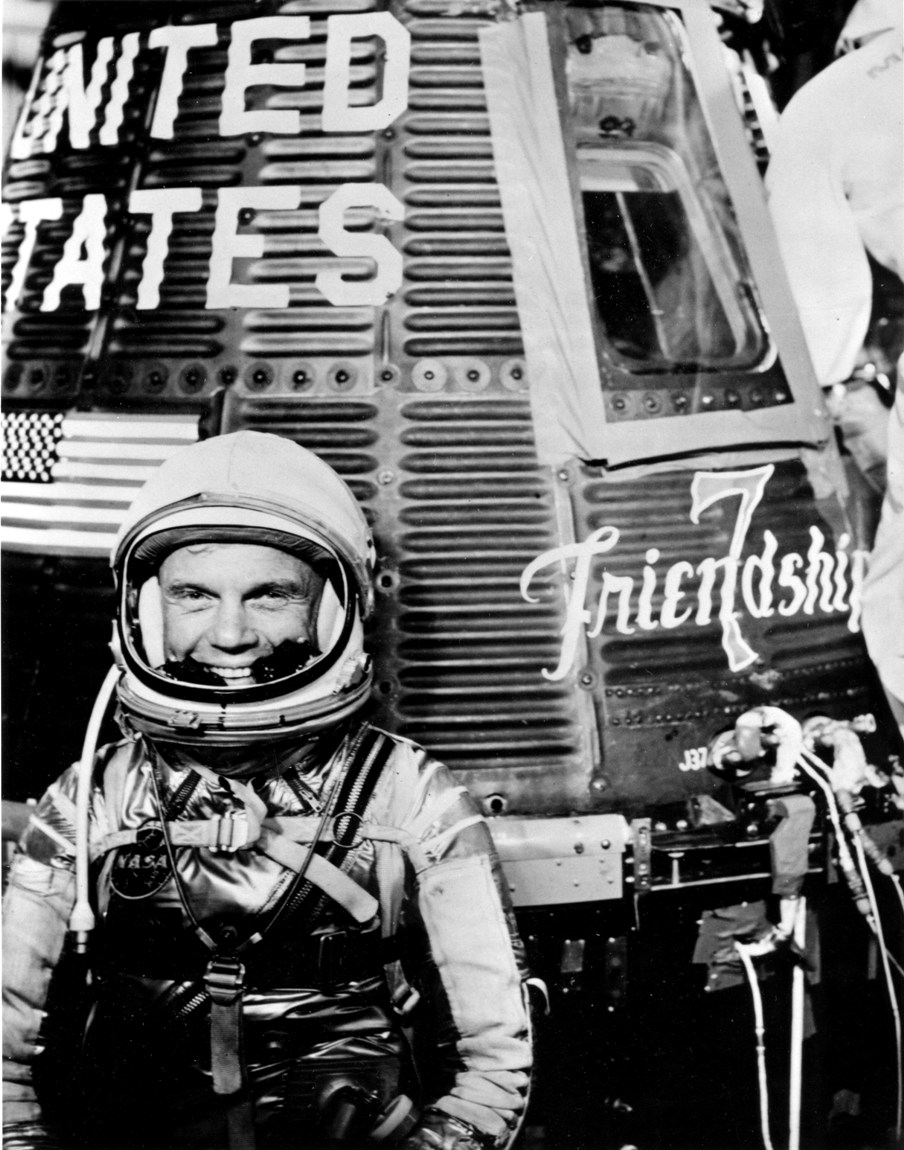

Two months earlier, President Kennedy spoke to the American public in a television address in response to the intimidation aimed at those who sought to obstruct desegregation at the University of Alabama. “This Nation was founded by men of many nations and backgrounds. It was founded on the principle that all men are created equal, and that the rights of every man are diminished when the rights of one man are threatened.

“It ought to be possible,” Kennedy said, “for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color. In short, every American ought to have the right to be treated as he would wish to be treated, as one would wish his children to be treated.”

King: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, Black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Kennedy: “Now the time has come for this Nation to fulfill its promise. The events in Birmingham and elsewhere have so increased the cries for equality that no city or State or legislative body can prudently choose to ignore them.”

King: “We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating, ‘for whites only.’”

Kennedy: “The heart of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. We face, therefore, a moral crisis as a country and as a people. It cannot be met by repressive police action. It cannot be left to increased demonstrations in the streets. It cannot be quieted by token moves or talk. It is time to act in the Congress, in your State and local legislative body, and above all, in all of our daily lives.”

While Kennedy’s prose is compelling, it is Dr. King’s poetic passion that glows with an urgency missing today: the moral will to overcome our divisions by recognizing our commonality.

“I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

“I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men are created equal.’

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

“I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

Can we live up to the dream of equality and brotherhood? Are we treating each other as we would like to be treated?

Comments