I remember watching a popular TV game show where a panel of celebrities would watch as three individuals would stand before them each claiming to be the same person.

A statement was read describing some unusual adventure or occupation. The task for the panelists was to ask a series of questions of each person in order to determine who the real individual was, exposing the others as fakes. But as the show revealed, sometimes the fakes could sound remarkably truthful.

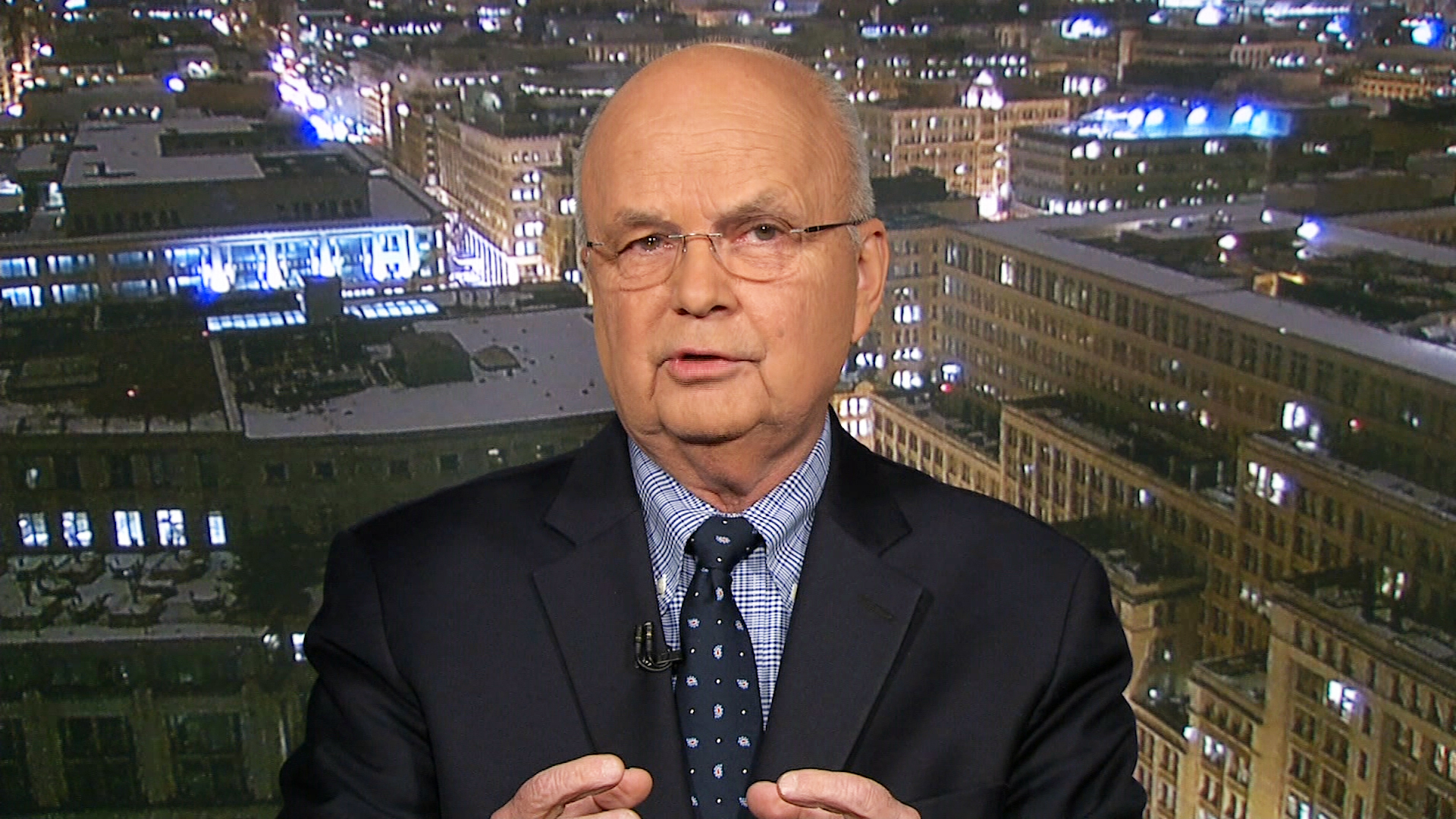

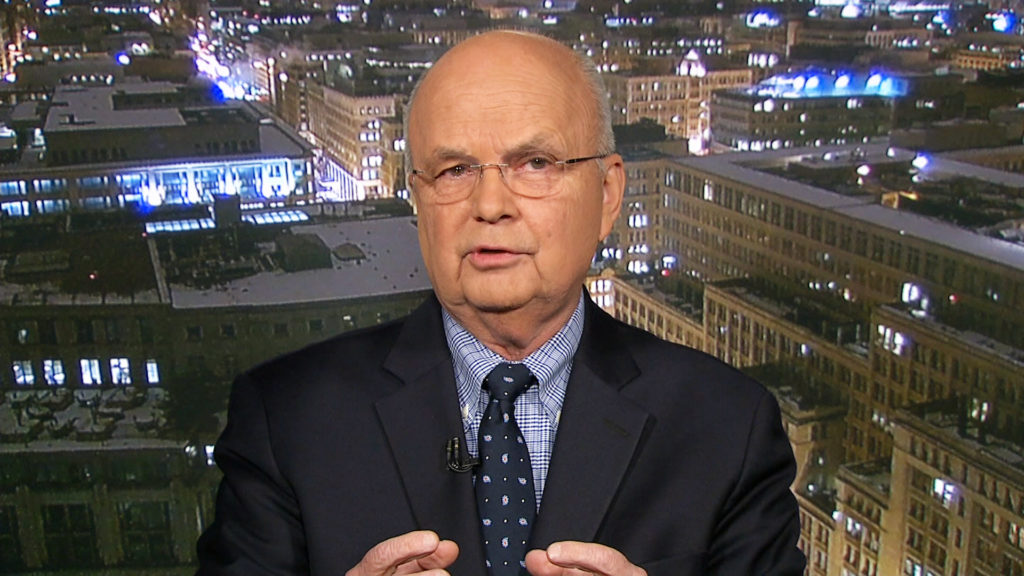

In an opinion piece entitled, The End of Intelligence (Apr.29), former director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Michael Hayden writes, “To adopt post-truth thinking is to depart from Enlightenment ideas, dominant in the West since the 17th century, that value experience and expertise, the centrality of fact, humility in the face of complexity, the need for study and a respect for ideas.”

Oxford defines “post-truth” as “Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

“President Trump both reflects and exploits this kind of thinking,” Hayden says.

In another opinion, writer Daniel Effron of the London Business School points out, “In his first 400 days in office, President Trump made more than 2,400 false or misleading claims, according to The Washington Post.”

At one time or other, most politicians mislead or deceive.

“I did not have sexual relations with that woman…” – Bill Clinton

“If you like your doctor, you can keep your doctor, period.” – Barrack Obama

Nonetheless, when it comes to out right lying, Trump excels beyond mere mortal politicians.

In 2017, Trump gave a speech to the Boy Scout Jamboree which, in Hayden’s words, “was overly political and occasionally tasteless. In the face of sharp criticism, the president said that the Scouts’ leader had called him to say it was ‘the greatest speech that was ever made to them.’

“Of course,” Hayden points out, “no such call ever occurred.”

“Intelligence work,” Hayden says, “reflects these threatened Enlightenment values: gathering, evaluating and analyzing information, and then disseminating conclusions for use, study or refutation.

“How the erosion of Enlightenment values threatens good intelligence was obvious in the Trump administration’s ill-conceived and poorly carried out executive order that looked to the world like a Muslim ban.

“That order was almost certainly not the product of intelligence analysis about the threat posed by immigrants from certain nations, but rather the president trying to fulfill a campaign promise based on exaggerated fears about immigrants and unfair criticism of the refugee vetting system. One former senior intelligence official told me that when the ban was announced internally, everyone was simply told to get on board.”

Imagine a surgeon getting ready to operate on a patient without tests or CT scans, or worse, ignores the available evidence and, instead goes into surgery based on a hunch or promise that he knows what to do, what to fix or remove.

Hayden’s point is that we abandon facts, analysis and truth at our peril.

“In this post-truth world,” Hayden says, “intelligence agencies are in the bunker with some unlikely mates: journalism, academia, the courts, law enforcement and science — all of which, like intelligence gathering, are evidence-based. Intelligence shares a broader duty with these other truth-tellers to preserve the commitment and ability of our society to base important decisions on our best judgment of what constitutes objective reality.”

Underline: important decisions; those decisions that have the potential to impact us all.

Does this matter to Trump supporters?

In Why Trump Supporters Don’t Mind His Lies (Apr. 29), Daniel Effron writes, “Some supporters no doubt believe many of the falsehoods. Others may recognize the claims as falsehoods but tolerate them as a side effect of an off-the-cuff rhetorical style they admire. Or perhaps they have become desensitized to the dishonesty by the sheer volume of it.

“New research of mine,” Effron continues, “suggests that this strategy can convince supporters that it’s not all that unethical for a political leader to tell a falsehood — even though the supporters are fully aware the claim is false.

“Consider some examples. When President Trump retweeted a video falsely purporting to show a Muslim migrant committing assault, Sarah Huckabee Sanders, the White House press secretary, defended him by saying, ‘Whether it’s a real video, the threat is real.’

“When asked about the false claim that Mr. Trump’s inauguration had drawn the biggest inaugural crowd in history, Kellyanne Conway, counselor to the president, suggested that inclement weather had kept people away.

“In each instance,” Effron says, “rather than insisting the falsehood was true, Ms. Sanders and Ms. Conway implied it could have been true. Logically speaking, the claim that more people could have attended the president’s inauguration in nicer weather does not make the crowd any bigger. But psychologically, it may make the falsehood seem closer to the truth and thus less unethical to tell.

“To find out if this strategy actually helps get politicians off the hook for dishonesty,” Effron “recently conducted a series of experiments. I asked 2,783 Americans from across the political spectrum to read a series of claims that they were told (correctly) were false.

“All the participants were asked to rate how unethical it was to tell the falsehoods. But half the participants were first invited to imagine how the falsehood could have been true if circumstances had been different. For example, they were asked to consider whether the inauguration would have been bigger if the weather had been nicer…

“The results of the experiments, published recently in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, show that reflecting on how a falsehood could have been true did cause people to rate it as less unethical to tell — but only when the falsehoods seemed to confirm their political views. Trump supporters and opponents both showed this effect.

“Again, the problem wasn’t that people confused fact and fiction; virtually everyone recognized the claims as false. But when a falsehood resonated with people’s politics, asking them to imagine counterfactual situations in which it could have been true softened their moral judgments.”

In other words, confirmation bias plays a large part in how voters view facts and truth.

Nonetheless, in the real world of you and me, I have seen more examples of people distrusting or shunning liars in favor of those they trust. Whether family, friends or coworkers, lying – habitually and consistently – carries consequences.

Hayden remarks, “The historian Timothy Snyder, stresses the importance of reality and truth in his cautionary pamphlet, On Tyranny. ‘To abandon facts,’ he writes, ‘is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power because there is no basis upon which to do so.’ ”

Every day, Trump stands before the country uttering falsehood after falsehood. For those who remain silent or continue to support him, we all suffer the ultimate consequence.

Comments