Is cobalt a savior for a greener planet?

Possibly, but at great cost.

The ferromagnetic metal—one of the most abundant of all metals found in the earth’s crust—is the essential element in all lithium-ion batteries used in cell phones, laptops, electric cars, and other products that depend on more efficient batteries. However, it is only economically feasible to mine in fewer than 20 countries. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has more than 4 million metric tons of it. The only other country that comes close to that amount is Australia at a little more than 1 million.

However, the DRC is anything but democratic because the vast supply coming out of the region requires the back-breaking, intolerable work of families and children—euphemistically called “artisanal miners”—digging by hand for pennies a day at the ultimate cost of their lives. The growing need for cobalt has led to a heart of darkness that would easily surpass that of author Joseph Conrad’s.

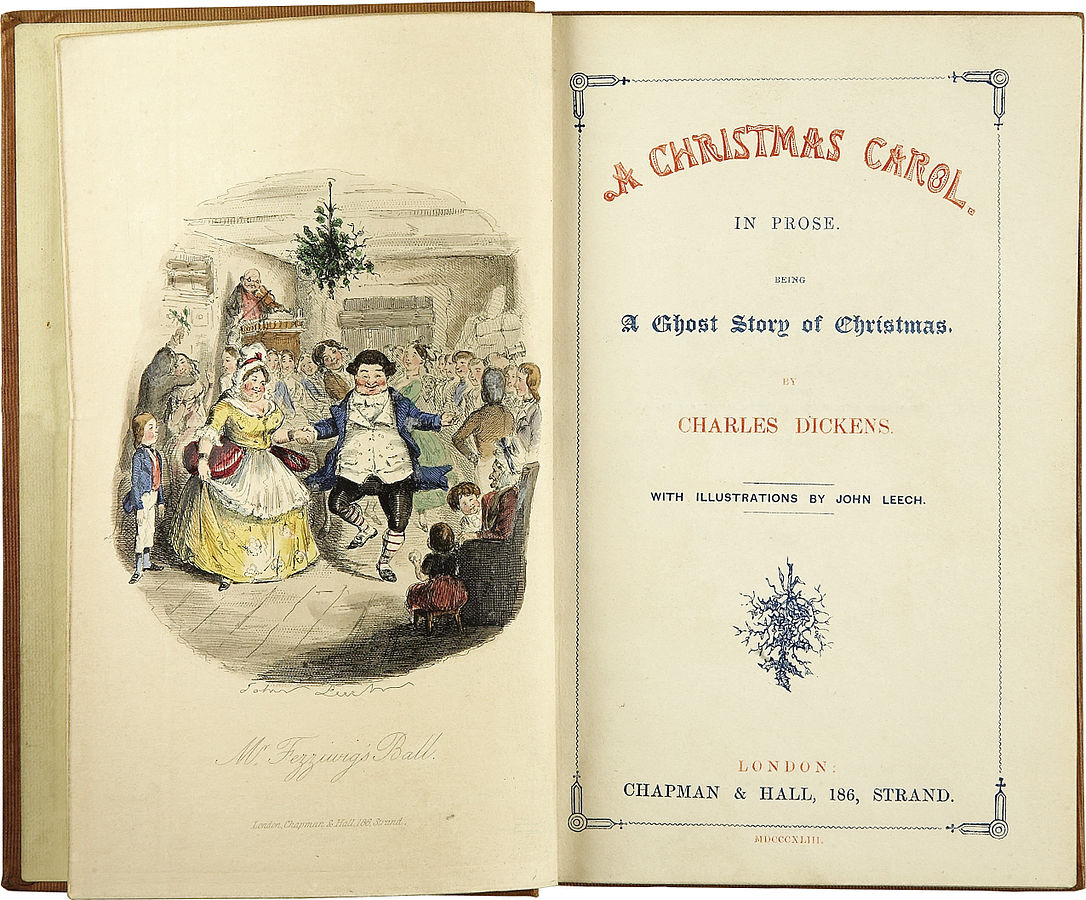

Author-activist Siddharth Kara took a journey through the DRC to research the beginning of a long chain of mining cobalt to its use in lithium-ion batteries for his recent book, Cobalt Red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives.

I have not read a more harrowing and compelling story whose consequences are a daily reality to those who literally give their lives helping to provide more effective batteries for the rest of the world. It’s a stunning indictment of the Congolese government in their treatment of the adults and children who have become slaves in the region.

In an interview with Joe Rogan, Kara says “that there was no corporate house that could ‘reliably’ and ‘justifiably’ claim to be working with clean cobalt.”

Those who work in the mines face inhalation of cobalt, arsenic, and uranium. Even those who live nearby have “very high levels of trace metals in their systems, including cobalt, copper, zinc, lead, cadmium, germanium, nickel vanadium, chromium, and uranium,” a researcher told Kara.

Cancers are common: breast, kidney, and lung. Those who work in and live around the mind face muscle and joint pain, headaches, gastrointestinal ailments; and reduced fertility in adults. Children who do not have direct exposure to the heavy metals but whose family members come home with dust on their clothes can suffer weight loss, vomiting, seizures, and neurological damage. And yet the work is a necessary part of life in a country that treats the impoverished like disposable tissue.

“If I work very hard for twelve hours,” one woman told Kara, “I can fill one sack each day.”

The price for those twelve hours is $0.80.

Living alone in a hut not far from the mines, the worker told Kara that her husband had died the previous year from a respiratory illness. They tried to have children, but she miscarried twice.

“I thank God for taking my babies,” she told Kara. “Here it is better not to be born.”

Kara describes watching a young girl standing alone on top of a large pile of mined dirt as she overlooks the devastation around her home as far as she could see.

“Beyond the horizon, beyond all reason and morality,” Kara writes, “people from another world awoke and checked their smartphones. None of the artisanal miners I met had ever seen one.”

Bribery exists on a massive scale throughout much of the chain and you quickly realize that any change in the process would require a tectonic shift in consciousness and action.

Comments