“A life is not important, except in the impact it has on other lives.” — Jackie Robinson

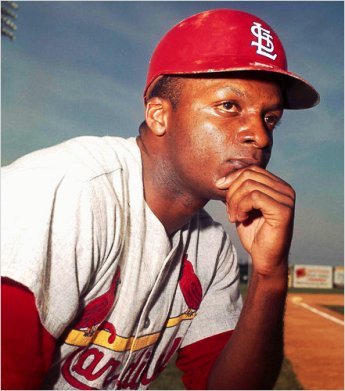

For eleven years, Curtis Charles Flood was a standout center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. According to Wikipedia, Flood “led the National League in putouts four times and fielding percentage twice, winning Gold Glove Awards in his last seven full seasons from 1963-1969. He also batted over .300 six times, and led the NL in hits (211) in 1964.”

However, as a new HBO documentary, The Curious Case of Curt Flood, makes clear that’s not what Flood will be remembered for most.

Curt Flood belongs in that distinguished yet unfortunate group of individuals who have taken a principled stand against something that most everyone agrees was wrong, but no one was willing to forfeit their career to correct.

In December 1969, Flood sacrificed his career and his reputation to fight baseball’s long-held reserve clause: “contained in all standard player contracts,” Wikipedia writes, “upon the contract’s expiration the rights to the player were to be retained by the team to which he had been signed… the player was not free to enter into another contract with another team. The player was bound to either (A) negotiate a new contract to play another year for the same team or (B) ask to be released or traded.”

For Flood that amounted to indentured servitude, slavery. “They say, ‘Curt Flood you make a lot of money. You make a hundred-thousand dollars a year,’ ” Flood said at the time, “but that’s not the point. I don’t want anyone to own me.”

Produced by Ross Greenberg and Rick Bernstein, the documentary explores Flood’s life in an out of baseball, but it’s central thesis remains the centerfielder’s fight to eliminate the reserve clause and move baseball out of the dark ages.

Cautioned by lawyer Marvin Miller that his chances were “a million to one,” and that even he won, “he’d collect no damages,” Flood’s response was, “still, if we won, it would benefit all the other players and the players to come.”

The myth is that a hero, particularly in sports, is defined by what he or she does on the field. In baseball, it’s a batting average, hits, homeruns, strikeouts, RBI’s, etc. The reality is that some heroes are those who are willing to take a morally courageous stand, and in so doing, make things better for others.

When Flood was traded from the Cardinals to the Phillies in 1969, the centerfielder believed that he should have the right to “shop” his talent to other teams; that he should have some measure of control over his own career. Baseball owners believed different and it was their belief that had been upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in previous cases.

While Dodger owner Branch Rickey was responsible for breaking baseball’s color barrier by hiring Jackie Robinson, Rickey was also well-known for being tight-fisted when it came to money for his players who had no control over their own contracts. Once they signed, it was either play ball by the owner’s rules or stop playing altogether. There was no middle ground.

Many of the Flood’s contemporaries agreed that the system was wrong, but what could you do?

However, Curt Flood did not possess the kind of personality that accepted the status quo. And although he eventually lost his case before the U.S. Supreme court in a 5-3 decision, “free agency” came about in 1975 after pitchers Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith played without contracts after expiration, arguing that their contracts could not be renewed if they were never signed. An arbitrator agreed and they were declared “free agents.”

Messersmith later said, “I did it for the guys sitting on the bench, the utility men who couldn’t crack the lineup with (the Dodgers) but who could make it elsewhere. These guys should have an opportunity to make a move and go to another club. I didn’t do it necessarily for myself because I’m making a lot of money. I don’t want everyone to think, ‘Well, here’s a guy in involuntary servitude at $115,000 a year. That’s a lot of bull and I know it.”

But before Messersmith and McNally, it was Curt Flood who put his career on the line. In a letter to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Flood wrote at that time, “I do not feel that I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes…. I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decisions.”

“Not many players, in those early years,” Miller said, “wanted to talk about the legalities of the reserve clause.”

And for good reason. Although the players’ representatives as a whole stood behind Flood, not a single active player wanted to step forward and take a stand because of the consequences such a decision would bring – banishment from baseball. When the case went to court, the only individuals who testified on behalf of Flood were former players Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg and former owner Bill Veeck.

While Curt Flood ended his career with a lifetime batting average of .293, 1,861 hits, 85 home runs, 851 runs and 636 RBI’s, his real legacy is that of a man who, in the face of impossible odds, stood up for fairness for others who would follow.

We need more Curt Floods, now more than ever.

Comments