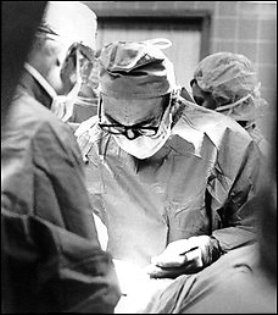

To say that Dr. Michael DeBakey was an extraordinary and innovative heart surgeon is a little like saying that Joe DiMaggio was a pretty good ball player.

Dr. DeBakey’s pioneering work in the field of cardiovascular surgery earned him international recognition. He is credited with inventing and perfecting scores of medical devices, techniques, and procedures, which have led to healthy hearts and productive lives for millions throughout the world… including my own!

Additionally, he is credited with developing the Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals – M.A.S.H. Units – used in the Korean War.

Dr. DeBakey earned an enviable reputation as a medical statesman. His writings are reflected in more than 1,600 published medical articles, chapters, and books on various aspects of surgery, medicine, health, medical research, and medical education, as well as ethical, socio-economic, and philosophic discussion in these fields. He led the movement to establish the National Library of Medicine, which is now the world’s largest and most prestigious repository of medical archives.

In 1969, he received the highest honor a United States citizen can receive, the Presidential Medal of Freedom with Distinction.

“Even in his 90s,” the New York Times wrote, “Dr. DeBakey arose at 5 a.m. every day, wrote in his study for two hours and then drove, often in a sports car, to the hospital, where he stayed until 6 p.m. After dinner, he usually returned to his library for more reading or writing before retiring after midnight.”

In March, 1999 I received a letter in response to a survey I sent Dr. DeBakey. That response appeared in my book, “What Do You Stand For?”

“The principles I live by are the ones my parents instilled in me from my earliest remembered years.

“By word and example, they taught me that the honor of my family name and a close family bond were more precious than anything, including wealth; that honesty, integrity, and trustworthiness will always stand the test of time; that kindness, compassion, altruism, patriotism, and public service lift the heart and nourish the soul; that self-discipline, industry, and determination can overcome almost all obstacles; and that the pursuit of excellence is not only fulfilling, but exhilarating.

“They showed me, by their own charitable deeds that it is, indeed, more blessed to give than to receive, and they insisted that everyone can, and should, make some contribution to humanity, no matter how small. It was, in fact, their model of humanitarianism and our exemplary family physician who sparked my early desire of becoming a physician.

“My parents’ principle of patriotism tested me when I was a young academic physician, on the threshold of my long-held dream of a career in medical research, teaching, and patient care. I had a number of research subjects that intrigued me and propelled me to spend long hours in the laboratory searching for answers to the causes and cures of several unsolved disabling and fatal diseases. Then America became involved in World War II. To enter the military at this stage meant interrupting my fervent desire to probe the deep chasms of medical mysteries – to surrender some of the most productive years of my carefully charted course.

“But the love of my country and its principles of freedom and personal responsibility that my parents taught me pulled me in the direction of signing up for service. Then I was declared an ‘essential’ member of the faculty at Tulane Medical School in New Orleans. I could stay in my post guilt-free and pursue the career that I had longed for since earliest childhood.

“I discussed my situation with my parents, who urged me to make my own decision, but who reminded me of every citizen’s responsibility. I knew what I must do: I asked the School to release me from the ‘essential’ category and joined the U.S. Army.

“At the end of the War, I was asked to delay my return to civilian status and remain yet another year in the Surgeon General’s Office to help organize the transfer and care of wounded servicemen to hospitals in this country. I readily agreed, and at the end of that period returned to Tulane Medical School and resumed a most fulfilling and enjoyable career there and, later, at Baylor College of Medicine in medical research, teaching, and patient care.

“I have never regretted allowing altruism to supersede self-interest by extirpating those fertile years from my academic career, and I was able, through good fortune, to pursue research and scholarly activities while I was in the service.”

Comments

Leave a Comment

It was my pleasure to become a heart surgeon during the pioneering years of the 1960s-1970s, at University of California, San Francisco Medical Center.

Back then, I would look at the lovely 22-year-old girl from Eureka with the atrial septal defect (hole in the heart) and wonder if our team would see her alive the following evening after open-heart surgery.

Everything Jim Lichtman has written, so briefly, especially the contribution by Dr. DeBakey himself, is true. It was my pleasure not only to spend two weeks with the master in 1972, but continue to know him through his generous work with USUHS, the medical school in Bethesda, MD, without which we would have no physicians or surgeons for the military services.

“Mike” and I last had lunch together 5 years ago, and he stood a full head taller than I at six-two, aged 95, articulate and brighter than even the younger surgeons at Bethesda.

Of note is the fact that he broke through a solid wall…the untouchable heart, which until 1947 was forbidden territory. He was led there by his WW II experience where he stepped into that no-man’s land by sheer necessity to save lives. He invented the heart-lung machine. His wife knitted by hand his first-ever dacron graft used to fix the heretofore unfixable aortic aneurysm, and developed an operation to save the doomed patient with a “dissecting” aneurysm.

How ironic it was then, at age 96, that he sustained exactly that…and was in his home Baylor Hospital with an ethics committee deciding that he was “too old” to have this operation. His wife stormed the meeting, banged on the table and stated: “My husband built this hospital, he trained most of you, he invented both the machine and the operation that he needs to live. Now get up and go fix him!” They did, he lived and spent the next three years continuing to teach, go to his office 8 hours plus each day, and in dying, left literally MILLIONS of us in his debt for saving our lives, those of our families and for teaching us the skills that we might carry it on.

Rarely does a physician break through a wall…Harvey Cushing did it going into the brain, Jonas Salk did it with the polio vaccine and Michael DeBakey did it by opening up heart surgery, so that now it is routine and we don’t wonder if the lovely lady will be with us tomorrow night.

Rest in peace Mike. You will never be duplicated and your “Welcome Home” should be fantastic!

I never knew Dr. DeBakey, but I most certainly felt his influence.

My most important mentor during training, Dr. William Blaisdell, was a DeBakey trainee. As Chief of Surgery at San Francisco General Hospital, the Blazer carried on DeBakey’s tradition of total dedication, and demanded it of us as well. Interesting, among his stories of DeBakey was that his residents understood not to trouble him with his complications; in fact, they admitted them to a separate wing, where the leader never trod. It was there that Dr Blaisdell, out of necessity, invented the axillo-femoral bypass, as a way to salvage an infected aortic graft. True story or not, Dr DeBakey was able to do what few of us who followed were: invent an entirely new field of surgery, the benefits are everywhere to be seen.