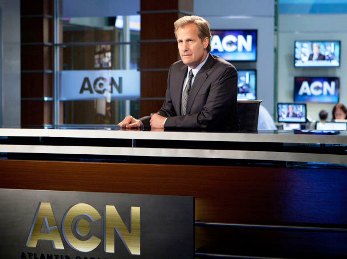

In order to understand why some in the media don’t like the new HBO series The Newsroom, here’s how TIME magazine’s James Poniewozik began his review:

“The fourth episode of Aaron’s Sorkin’s The Newsroom is called ‘I’ll Try to Fix You.’ That may as well be the title of the whole series. Like Sorkin’s The West Wing, the show wants to fix America, this time through the story of Will McAvoy, a successful, cynical and bland cable-news anchor who decides that he, and journalism, and yea, democracy, can do better.

“Which means what?” Poniewozik asks.

“Will’s producer/ex-girlfriend MacKenzie McHale explains: ‘Reclaiming the fourth estate. Reclaiming journalism as an honorable profession. A nightly newscast that informs a debate worthy of a great nation. Civility, respect and a return to what’s important.”

And that’s just some of the heart of ethics. Ethics is not about the way things are, it’s about the way things should be. It’s about striving to make better decisions based on the facts, not a bunch of controversial fluff and emotional fear. It’s about basic civility for the individual sitting next to you, even if you don’tagree with that individual. It’s about practicing the necessary self-restraint to make your point instead of shouting over your adversary. It’s about not seeing everyone who disagrees with you as an adversary.

Halfway into his review, I began to understand where Mr. P’s dislike comes from. “The West Wing, which also idealized a discredited institution, was hardly speech-shy, but it had richly drawn, plausible, memorable characters. The Newsroom has media-criticism delivery devices.”

Mr. P is a wee bit defensive about his own “discredited institution.” And there are plenty examples to support the decline of media in general and cable news in particular.

However, I know at least two people who might like the central premise of The Newsroom – Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel, authors of the (2001) book, The Elements of Journalism. “We need news to live our lives,” they write, “to protect ourselves, bond with each other, identify friends and enemies. Journalism is simply the system societies generate to supply this news. That is why we care about the character of news and journalism we get: they influence the quality of our lives, our thoughts, and our culture.”

Journalism’s influence and power should be treated as a public trust. It should inspire credibility, responsibility and integrity in the information it puts forth.

“As a teacher,” ethicist Michael Josephson says, “[journalism] should inform, clarify and explain about matters of social consequence and know without pandering unduly to public dispositions to be entertained and titillated.”

Last Friday we saw the beginning of the latest torrent of titillation with the release and soon to be, wall-to-wall interviews, of John Edwards’ mistress Rielle Hunter whose tell-all covers “One of the biggest political scandals of all time,” “a modern-day tragedy,” the publisher promises.

“What should citizens expect of [newspeople]?” Kovach and Rosenstiel ask.

“Journalists must make the significant interesting and relevant…. Journalism is storytelling with a purpose. That purpose is to provide people with information they need to understand the world. The first challenge is finding the information that people need to live their lives. The second is to make it meaningful, relevant, and engaging.”

While the Hunter story may be relevant to those with a subscription to The Star, The National Inquirer; or have bookmarked Radar online; after reporters have covered the story from every angle but the international space station, is it really necessary for ABC reporter Chris Cuomo to take up an additional hour of airtime to rehash details from the horse’s mouth because she has a tell-all book?

“Since there are no laws of journalism, no regulations, no licensing, and no formal self-policing, and since journalism by its nature can be exploitative,” Rosenstiel and Kovach say, “a heavy burden rests on the ethics and judgment of the individual journalist and the individual organization where he or she works.”

The Newsroom is not perfect. While Woodward and Bernstein may not agree with some of the preachier portions, or backstage drama, I think they would agree with many of character’s principles.

So, Mr. Poniewozik, after you have finished reviewing next season’s American Idol, Real Housewives of Whatever City Comes Next, or the latest group of mind-numbing, political junkies who are overpaid to talk over one another about making thirty ratings-grabbing minutes out of the next political mole hill, you might want to tune in – just occasionally – to a show that seeks to have rational dialog, and intelligent conversation about information that actually has an impact on people’s lives.

Maybe we need a few more homilies these days, Mr. P, if for no other reason than to balance out the titillating tabloid noise that passes for news and critical opinion these days.

Newsroom aspires to remind us of what is important and why. It brings back the ancient but necessary notion of honestly debating an issue instead of grinding away at our sensibilities with another unnecessary story about a politician’s mistress with a book to sell.

Smart, responsible, trustworthy newspeople are important precisely because “they influence the quality of our lives, our thoughts, and our culture…. In the end,” Kovach and Rosenstiel remind us, “journalism is an act of character.”

“In the old days, we did the news well,” The Newsroom’s elder statesman Charlie Skinner tells anchor McAvoy. “You knowhow? We just decided to.”

Right now, we could all benefit from a lot more practitioners of that sentiment. Given a choice between optimism and cynicism, I’ll stand with those who know we can always do better and should.

Comments