This week, I’m focusing on what may be the most endangered quality in public life: integrity.

Over the next 5 days, I’ll spotlight five U.S. Presidents who, when faced with defining moments, chose character over calculation. These men didn’t just hold office—they upheld a moral compass, often at personal or political cost. Their stories remind us of what principled leadership looks like and why it still matters.

* * *

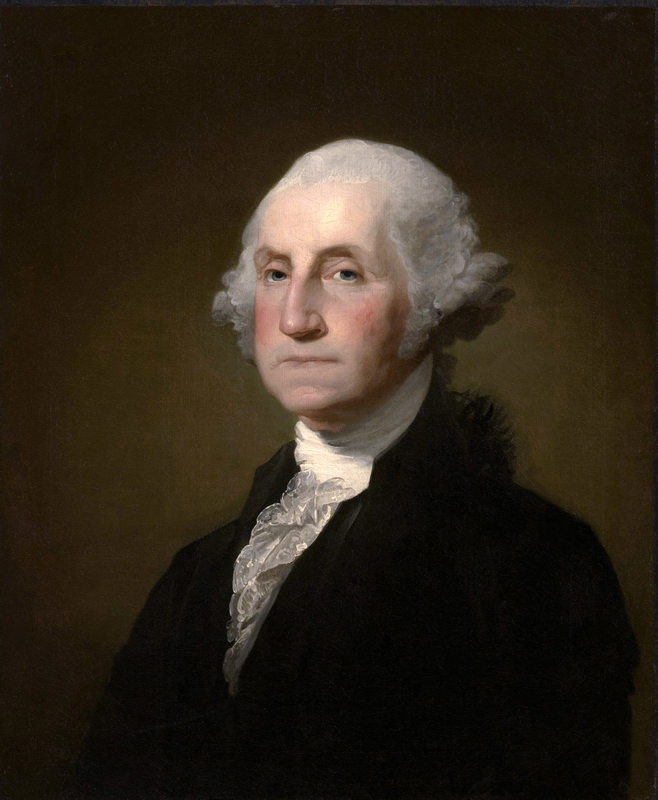

In a time when most leaders held on to power until death—or were forced out—George Washington did something remarkable. He gave it up. After two terms as president, with no law requiring him to step down, Washington chose to walk away. He knew the example he was setting. And he knew the country needed something more than strength. It needed restraint.

This wasn’t his first act of humility. After leading the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War, Washington returned his commission to Congress in 1783. He didn’t demand power, reward, or recognition. He simply went home to Mount Vernon. That one act stunned the world. Even King George III is reported to have said that if Washington truly gave up power, “he will be the greatest man in the world.”

Eight years later, the country called him back. He was unanimously elected as the first president under the Constitution. He accepted the job—not out of ambition, but out of obligation. And when his second term came to an end, many urged him to stay. The country was still fragile. His leadership was considered essential. But Washington declined. He believed staying too long—even with good intentions—posed a threat to the new democracy.

“The line between liberty and despotism,” he once wrote, “is often thinly drawn.”

In his 1796 Farewell Address, Washington made his reasons clear. “The acceptance of, and continuance hitherto in, the office to which your suffrages have twice called me,” he said, “have been a uniform sacrifice of inclination to the opinion of duty.” He never saw the presidency as his. It was a trust placed in him by the people—and he believed that trust should never be abused.

Washington’s departure set the most important precedent in American political history: that power, even at the highest level, must be temporary. It doesn’t belong to the officeholder—it belongs to the people.

That’s more than a political statement. It’s an ethical one. Washington understood that the strength of the republic wasn’t measured by how long one man stayed in office. It was measured by whether the office itself could outlast any one man.

Even in leaving, he remained focused on the long-term health of the country. He warned against regional divisions, factional politics, and foreign entanglements. “It occurs as matter of serious concern,” he wrote, “that any ground should have been furnished for characterizing parties by geographical discriminations.” These weren’t abstract concerns. He saw how quickly power could be distorted when loyalty shifted from country to party.

Washington’s exit didn’t signal retreat—it signaled responsibility. It reminded the country that public service has an endpoint. That leadership, when practiced well, often means knowing when to step aside.

In today’s political climate—where some leaders do everything they can to hold onto power—Washington’s decision still stands as one of the greatest acts of moral clarity in public life. He could have justified staying. Many wanted him to. He chose not to.

That decision didn’t weaken the presidency. It strengthened it.

Washington didn’t define leadership by how much authority he could accumulate. He defined it by how much trust he could earn—and how carefully he could protect it.

In choosing to walk away, Washington gave the country something far more valuable than longevity. He gave it a model of character. A lesson in humility. And a reminder that real leadership is grounded not in control, but in conscience.

Comments