During a session of Contemporary Ethical Issues, a class taught by me and Professor Stephen Ambra at the New Hampshire Technical Institute, the subject of bullying came up, which prompted me to ask, “Show of hands, how many of you have ever been bullied?”

Out of 36 students, I was surprised to discover an overwhelming majority had faced ridicule, coercion, harassment, or physical abuse. In a final paper, one student wrote that the class had had a significant affect on him since he himself had bullied others.

This brings me to the recent case of Dharun Ravi, the Rutgers University student who was found guilty of using a webcam in 2010 to spy on Tyler Clementi, his gay roommate having sex with another man in his room. Particularly shocking was the fact that Ravi sent out Twitter messages to others announcing what he was watching. After learning of the messages, a depressed Clementi jumped from a bridge a few days later.

While Ravi was not charged with causing Tyler Clementi’s death, the jury convicted the 20-year-old former student of all 15 counts against him including bias intimidation, invasion of privacy and tampering with a witness and evidence.

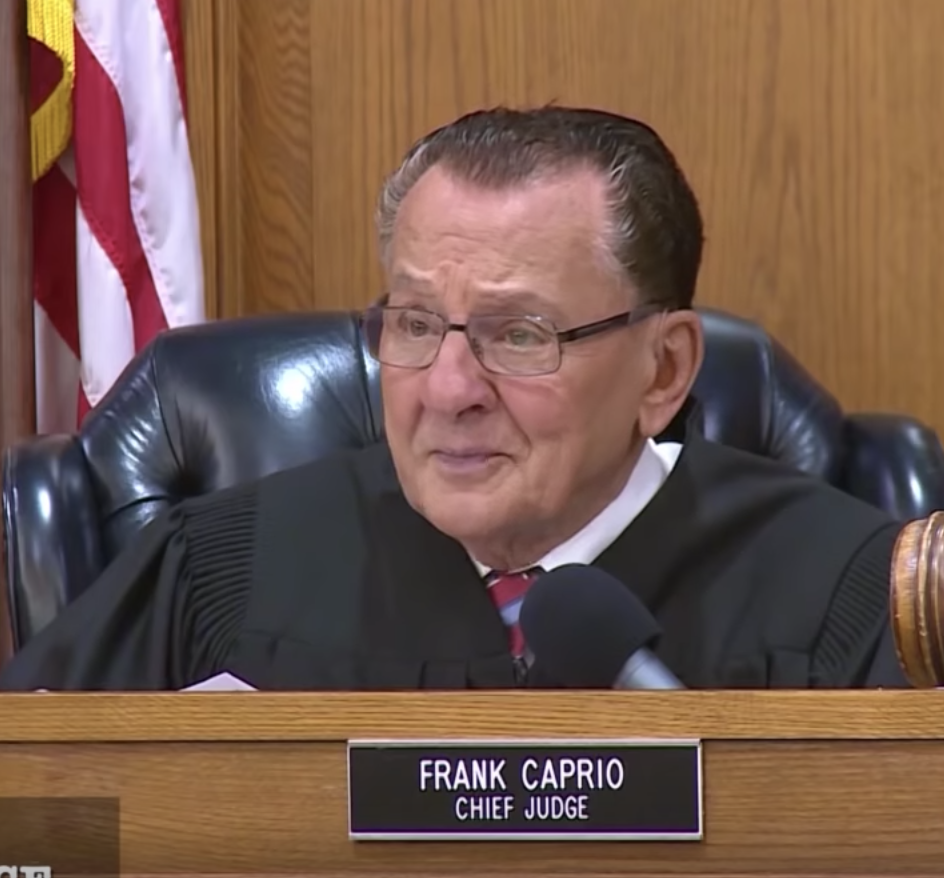

In issuing Ravi’s sentence, New Jersey Judge Glenn Bermansaid, “I heard this jury say guilty 288 times — 24 questions, 12 jurors, that’s the multiplication, and I haven’t heard you apologize once.” Berman then sentenced Ravi to 30 days in jail and three years’ probation. While the judge could have imposed a maximum of 10 years, he said that he felt the sentence was “constructive,” adding, “I do not believe he hated Tyler Clementi. I do believe he acted out of colossal insensitivity.”

What may be surprising to some is the fact that among Ravi’s supporters is a group of gay activists.

In the New York Times (May 20), Kate Zernike writes that many gay rights advocates believe that, “As repugnant as his behavior was… it was not the blatantly bigoted or threatening actions that typically define hate crimes. Some fear that a sentence that overreaches might provide tinder to antigay sentiment…

“While Mr. Clementi’s suicide in September 2010 galvanized public attention on the struggles of gay, lesbian and bisexual teenagers, the question of how to punish Mr. Ravi has revealed the deep discomfort that many gay people feel about using the case as a crucible. ‘You’re making an example of Ravi in order to send a message to other people who might be bullying, to schools and parents and to prosecutors who have not considered this a crime before,’ said Marc Poirier, a law professor at Seton Hall University who is gay and has written about hate-crimes legislation. ‘That’s a function of criminal law, to condemn as general deterrence. But I think this is a fairly shaky set of facts on which to do it.’ ”

From an ethical standpoint, the case seems to pit justice for Clementi’s parents against compassion for a student whose moment of “colossal insensitivity” appeared to trigger the death of his roommate.

While the issue of bullying has gained national attention, deservedly so, in looking at this case, one question kept coming up for me:

What would the Dali Lama’s response be?

In What Do You Stand For?, I had the opportunity to discuss the importance compassion with His Holiness particularly with regard to the issue of justice: “How do you reconcile your sense of compassion and love with your objective of achieving justice and freedom for Tibet? “Do you ever get angry with those who express violence to the Tibetan people?”

“We should begin by removing the greatest hindrances to compassion: anger and hatred,” His Holiness writes. “As we all know, these are extremely powerful emotions, and they can overwhelm our entire mind…This is because anger eclipses the best part of our brain: its rationality. So the energy of anger is almost always unreliable. It can cause an immense amount of destructive, unfortunate behavior.

“It is possible, however, to develop an equally forceful but far more controlled energy with which to handle difficult situations. This controlled energy comes not only from a compassionate attitude, but also from reason and patience. These are the most powerful antidotes to anger… So, when a problem first arises, try to remain humble and maintain a sincere attitude and be concerned that the outcome is fair.

“Of course, others may try to take advantage of you, and if you’re remaining detached only encourages unjust aggression, adopt a strong stand. This, however, should be done with compassion, and if it is necessary to express your views and take strong countermeasures, do so without anger or ill intent… Retaliation based on the blind energy of anger seldom hits the target.”

His translator and assistant, the Venerable Lhakdor, offered this example:

“[One] monk from Namgyal Monastery was in a Chinese prison for seventeen years. When he managed to leave Tibet and come to India, he met with His Holiness. One day, he mentioned to His Holiness that while he was in prison he faced danger on several occasions. His Holiness assumed that his life was in danger. But [the monk] continued, ‘I was in danger of losing compassion towards the Chinese.’ ”

So, how would you respond to the sentencing of Dharun Ravi? Do you favor justice or compassion? Is it possible to apply a sentence that would satisfy both ethical values?

Comments

Leave a Comment

A man chose to criminally invade the privacy of a fellow student; to ridicule, mock and HUMILIATE; and make fun of a lifestyle he disagreed with, and Lie about it, and hinder his prosecution. The viciousness of what he did is self-evident with the tragic loss the sentence was way too light [from] the Judge. [An] appeal [is] further insult. I don’t know how they sleep at night.