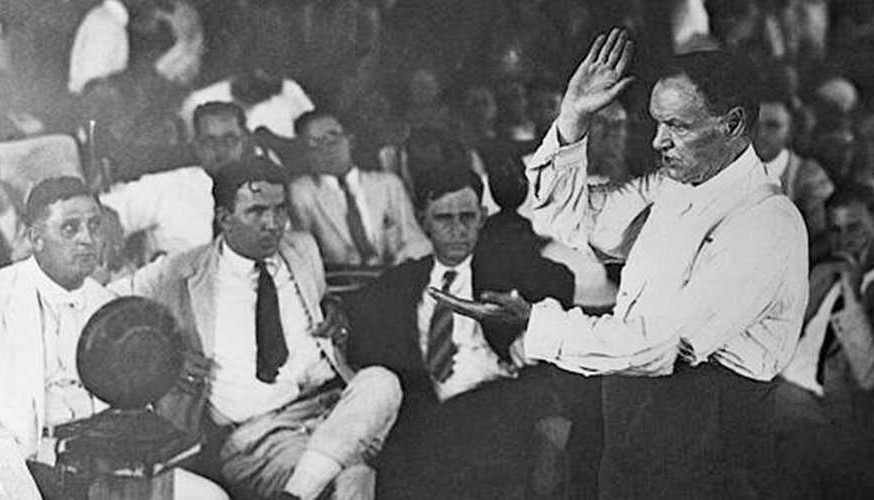

Clarence Darrow for the defense.

In 1925, Dayton, Tennessee, became ground zero for religious extremism.

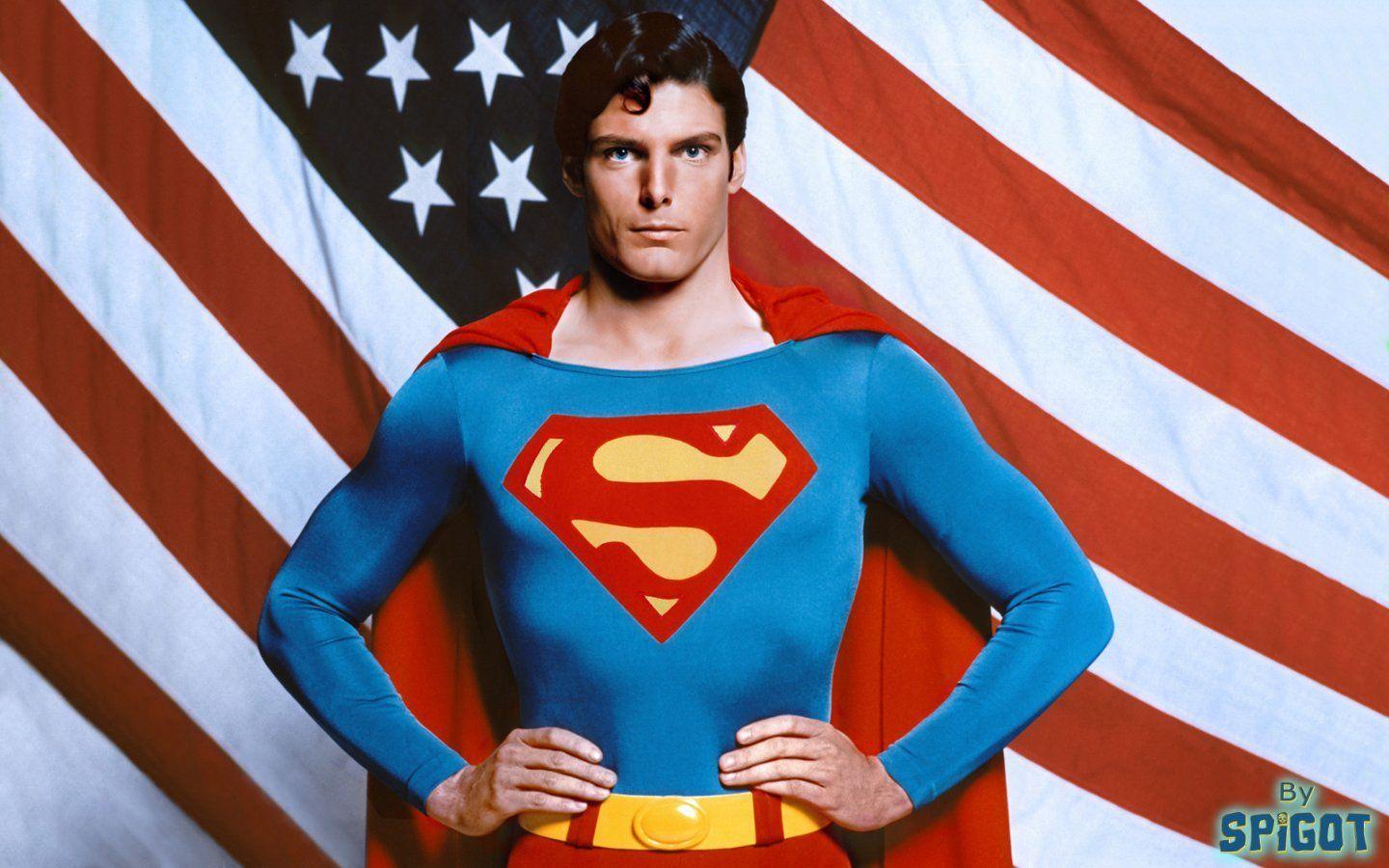

High school teacher John Scopes was charged with violating a state act making it illegal to teach Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution in any state-funded school. When noted criminal attorney Clarence Darrow appeared for the defense, the trial received national attention. But the prosecution employed its own legal titan—three-time presidential candidate and evangelist William Jennings Bryan.

During the trial, in an impassioned speech, Darrow addressed the packed courtroom with inescapable logic, and a prophecy.

“Can’t you understand,” Darrow says, “that if you take a law like evolution and you make it a crime to teach it in the public schools, tomorrow you can make it a crime to teach it in the private schools? And tomorrow, you may make it a crime to read about it. And soon, you may ban books and newspapers. And then you may turn Catholic against Protestant, and Protestant against Protestant, and try to foist your own religion upon the mind of man. If you can do one, you can do the other. Because fanaticism and ignorance are forever busy and need feeding.”

Beaufort County, South Carolina, is Tennessee’s legacy for right-wing attacks on public education.

Book banning in state-funded schools first gained national attention in Florida with Moms for Liberty, a “parental rights” group whose definition of liberty comes with conditions and a steep price.

Scott Pelley’s report on the CBS news show 60 Minutes points to 97 books that the group demanded to be banned in Beaufort County. It began, as Pelley points out in his report, when Dick Greier, the vice chair of the school board, received an email “from a citizen saying that ‘These 97 books that we’ve heard about online that should be banned in a school.’”

How were the books selected? A website called BookLooks recruited volunteers to read and assess books based on the site’s standards. When negative reviews of the 97 books appeared on the site, Moms for Liberty acted.

The book ban was used as a conspiratorial gateway for activists to threaten librarians and others, labeling them “groomers,” a term used to mark individuals as child molesters who were “grooming” children for sex. Fearing violence, school superintendent Frank Rodriguez pulled all 97 books from libraries in the school system.

However, using a protocol like BookLooks, Beaufort had 146 community volunteers read and discuss the books and take a vote. The final verdict: five of the 97 books that Moms for Liberty wanted banned “were judged too graphic in sex or violence; 92 returned to the school libraries.

“Parents have the right to determine what their children are taught and what they’re allowed to read,” Greier told Pelley. “No doubt about it. But what we’re having a problem with are parents that want to determine what other parents’ rights are for their children to read what they want.”

However, Beaufort county libraries already have a plan in place whereby parents can utilize an “opt-out” form: “do not allow my child to check out any school library materials…without my approval…”

In the case of Moms for Liberty—a group that has been labeled as extremist by the Southern Poverty Law Center—the Beaufort book ban is yet another attempt by a group to impose their morality on others.

In a foreword to Darrow’s memoir, Attorney for the Damned, former U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas foretold Beaufort’s solution to banning.

“Darrow used the law to promote social justice as he saw it. Yet the law and the lawyers were to him reactionary forces. Their faces were usually turned backward. Great reforms came not from within the law but from without. It was not the judges and the barriers who made the significant advances toward social justice. They were made in conventions of the people and in legislative halls. Yet Darrow, working through the law, brought prestige and honor to it during a long era of intolerance.”

Nearly 100 years later, that same intolerance is walking us backward.

Comments