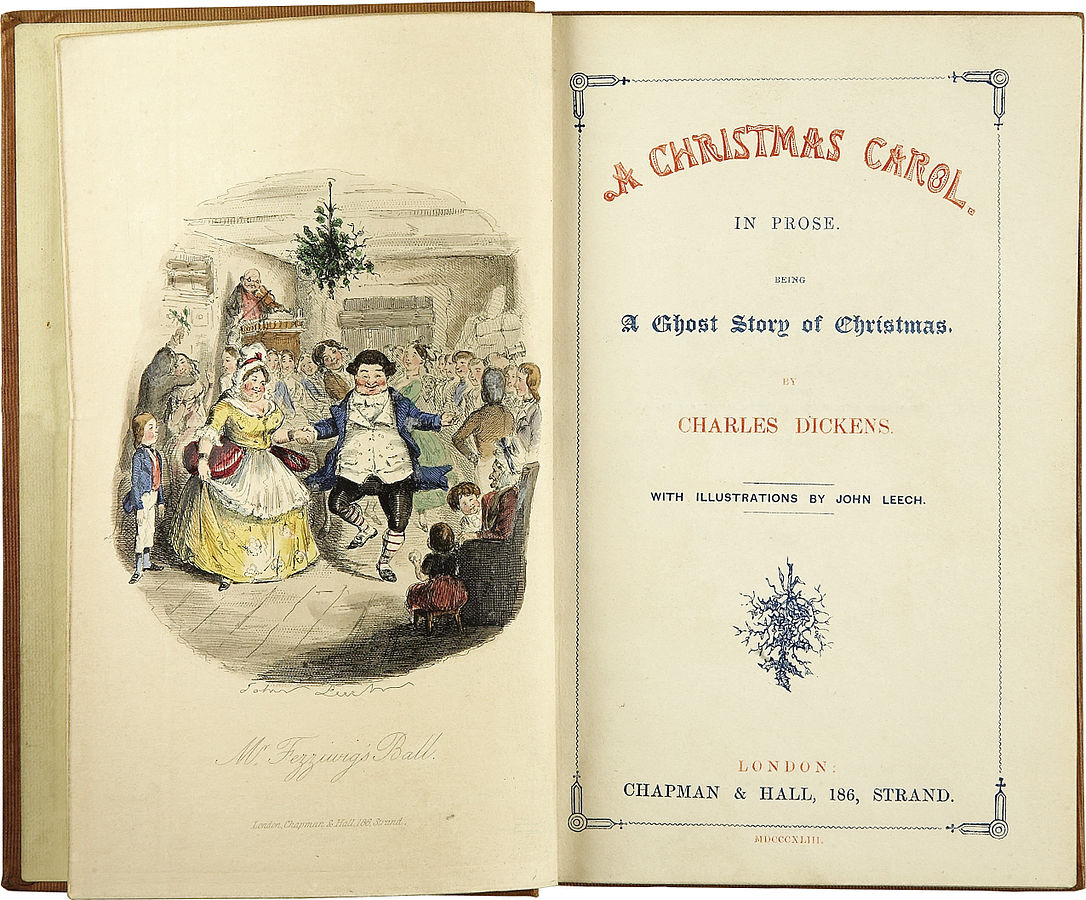

Every December, I look forward to reading and watching Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

While there are countless versions of the classic, I always return to the film with Reginald Owen as Scrooge, not only because Owen embodies the part, but also because it features Gene Lockhart as Bob Cratchit. A brilliant character actor with a gift for sincerity, Lockhart brings Cratchit to life in a way that embraces his humility and warmth, and his performance in the 1938 version is among his best.

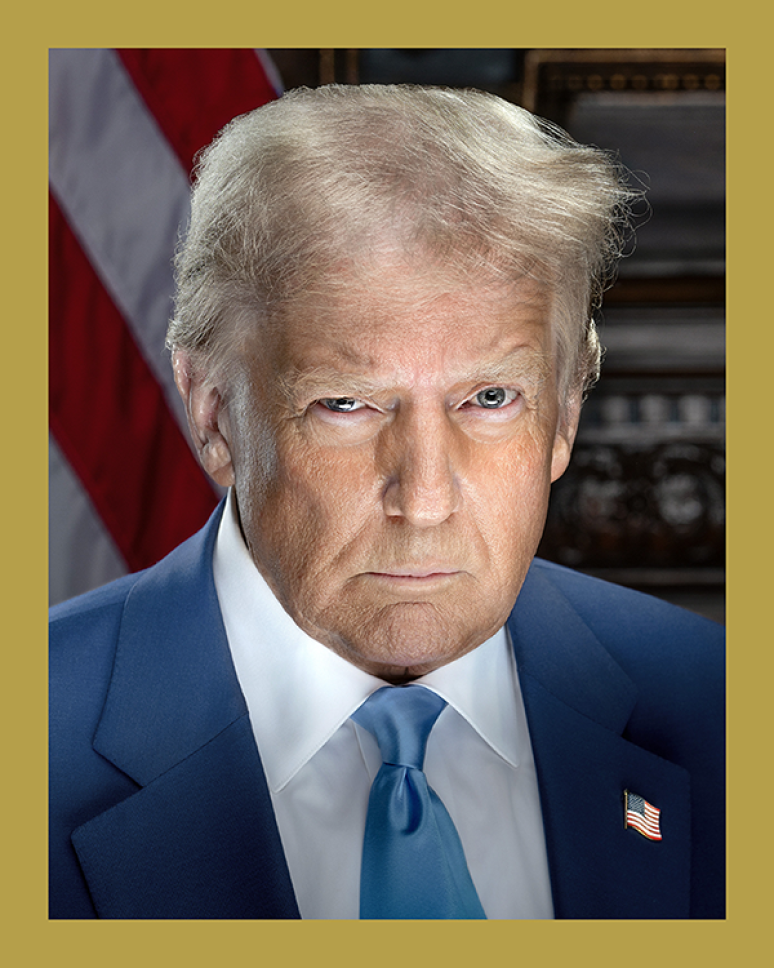

The story turns on Ebenezer Scrooge–whose name itself pretty much foreshadows what’s to come. Scrooge is a man whose loss of love sends him from youthful, bright, and promising to an old man frozen by fear and isolation. When he finally awakens to compassion and generosity, we understand the dramatic path of redemption that has carried A Christmas Carol through generations.

But Dickens is after something more than Scrooge’s personal salvation. The deeper message is not simply that one man can change, it is that one man’s change can change the world around him.

This idea sits quietly beneath the surface of Scrooge’s turmoil. It is the moral force that drives Dickens’ imaginative story. He knew well the England of his day: child labor, debtors’ prisons, and industrial indifference. And he understood that poverty was never the natural result of a person’s character. It was the natural result of a society that refused to see those who carried the weight of it. In Scrooge, Dickens creates the perfect symbol of that refusal: a man who believes that suffering “decreases the surplus population,” and that the fate of the poor is “not my business.”

Dickens’s point is that indifference… not poverty itself, is the greater sin.

Yet Dickens also suggests something hopeful: that moral blindness is reversible. Scrooge’s redemption is emotional, yes, but it only becomes meaningful when it becomes altruistic. His transformation is not measured by how he feels on Christmas morning. It is measured by what he does. He doubles Cratchit’s salary, becomes a “second father to Tiny Tim,” joins his young nephew and future daughter-in-law in celebration, and engages with his community in a way he never imagined possible.

In Dickens’ world, generosity is not a sentiment. It is a conscious act of giving ourselves. Dickens is illustrating a simple truth: the moral transformation of one person can lift the lives of many.

It’s the same message offered in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, when an angel reminds a defeated and desperate George Bailey that “Each man’s life touches so many other lives.”

What Dickens ultimately gives us is a story about the urgency of moral responsibility. Scrooge sees what his life will become if he continues to hide behind the false security of wealth and isolation. His transformation endures because it mirrors a truth we all face: each of us needs a reminder, now and then, to turn back toward the better parts of ourselves.

The message is clear: decency is not just a personal virtue; it is a public obligation. Compassion is not seasonal; it is the daily measure of a just society.

Comments