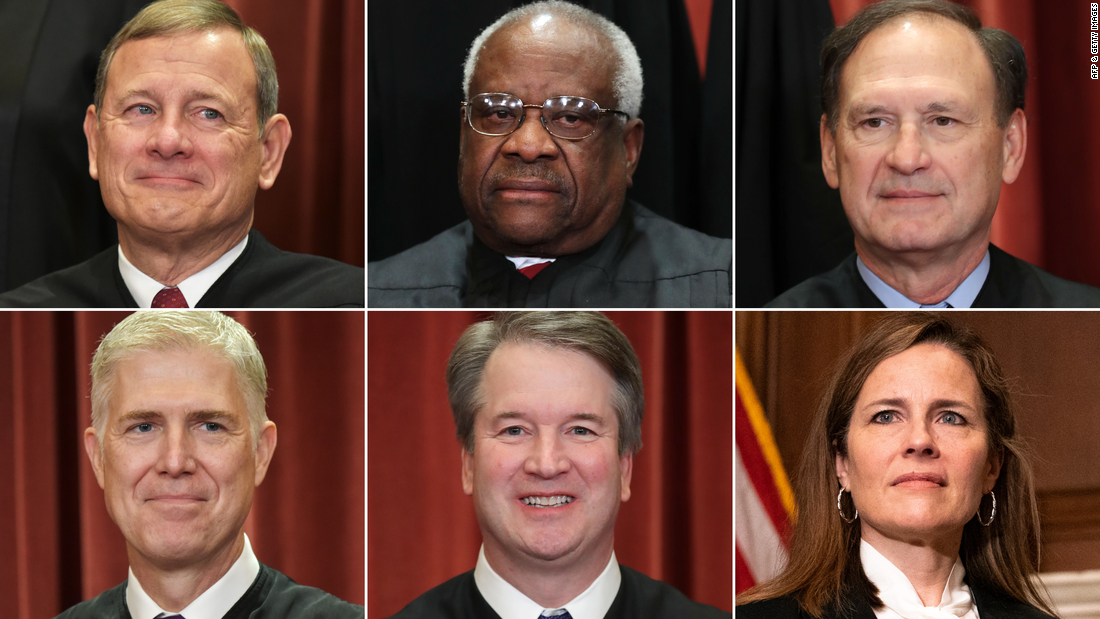

Political pundits and experts love to predict. In the case of conservative Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, it would seem all the experts had a better chance of going to their local carnival, dropping a nickel in Mr. Predicto, and reading the response on air from that little pop-out card.

When it came down to a final decision on President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, Chief Justice Roberts proved them all wrong.

And that’s the good news.

The bad news is The Roberts Decision – as it’s now being called – has unleashed a whole new series of “expert” speculation on why he made his decision. Some see it as a sure-fire win for Romney and the Republicans because “it ignites the base.” Democrats see it as a vindication for a long overdue health care reform. I don’t think either reasoning is wholly accurate.

Pulitzer Prize winning opinion writer Thomas Friedman has come closest to what the Roberts decision means: “I think it was inspired by a simple noble leadership impulse at a critical juncture in our history — to preserve the legitimacy and integrity of the Supreme Court as being above politics. We can’t always describe this kind of leadership, but we know it when we see it and so many Americans appreciate it.

“This is still a moderate, center-left/center-right country,” Friedman writes, “and all you have to do is get out of Washington to discover how many people hunger for leaders who will take a risk, put the country’s interests before party and come together for rational compromises. Why do we all jump up and applaud at N.B.A. or N.F.L. games when they introduce wounded Iraq or Afghan war veterans in the stands? It’s because the U.S. military embodies everything we find missing today in our hyperpartisan public life. The military has become, as the Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel once put it, ‘the last repository of civic idealism and sacrifice for the sake of the common good.’ ”

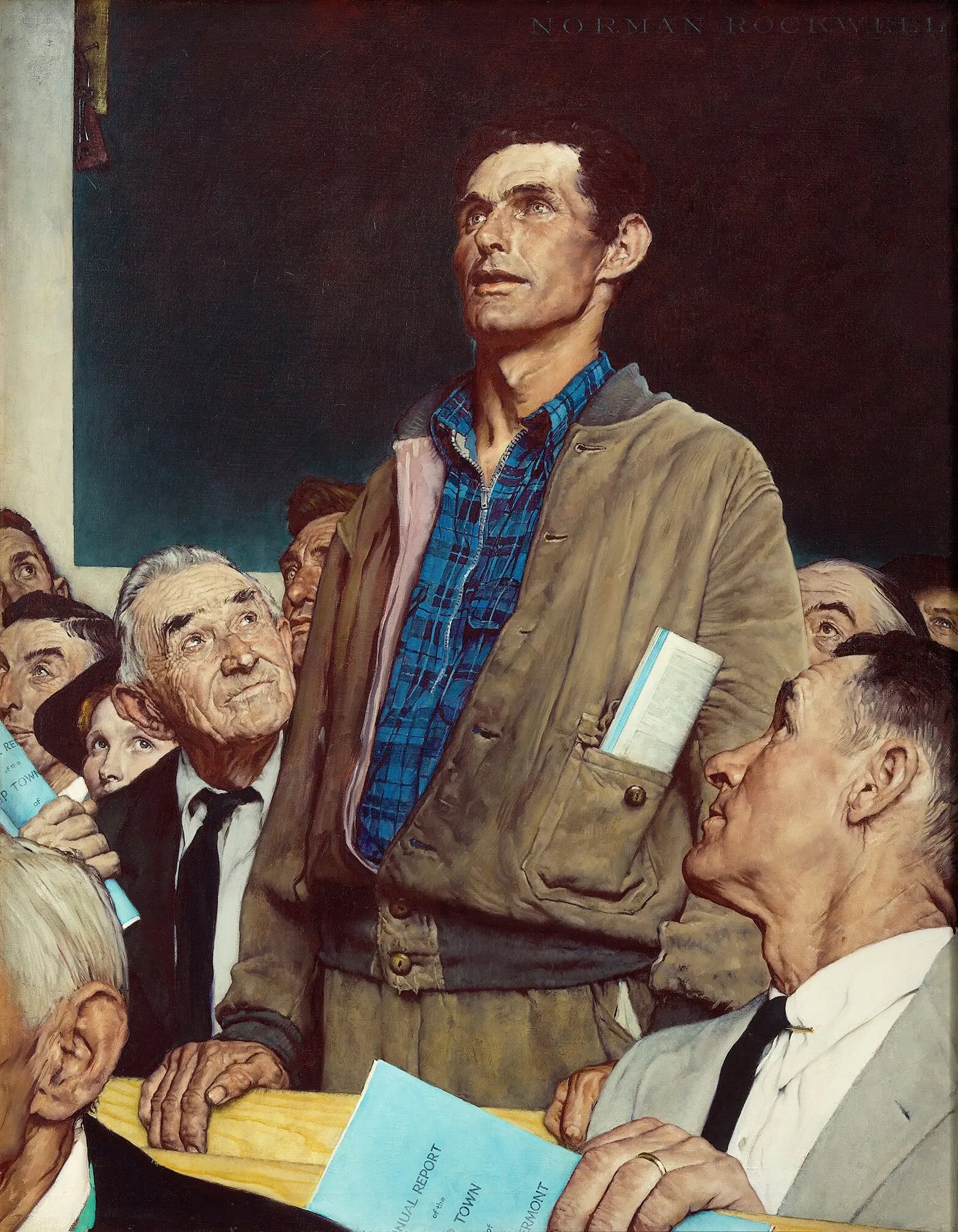

Last Friday, I wrote about statesmanship and the public good in considering compromise. Most rational Americans want – need– a clear and convincing policy of compromise from their elected officials. Four years into the worst economy since the Great Depression, Americans are asking: Where are those leaders who can demonstrate the unity of compromise?

Not long after the Supreme Court decision was announced, House Speaker John Boehner and Wisconsin congressman Paul Ryan reflexively declared that they were going to bring yet another vote to the House floor to repeal “Obamacare” which will – as it has in the past 30-odd votes – be rejected by the Senate. (And these people actually get paid to do this.)

Leadership is not easy. It frequently requires individuals to take a risk, typically for the sake of a principle, (a pledge to never raise taxes is not a principle). Whether you call the individual mandate provision requiring everyone to have health insurance a tax or a penalty, the result is the same: everyone needs to be accountable. Justice Roberts took a statesman-like approach to the issue in spite of considerable pressure – we have since learned – to do otherwise.

“Roberts undertook an act of statesmanship for the national good by being willing to anger his own ‘constituency’ on a very big question,” Friedman writes. “But he also did what judges should do: leave the big political questions to the politicians. The equivalent act of statesmanship on the part of our politicians now would be doing what Roberts deferred to them as their responsibility: decide the big, hard questions, with compromises, for the national good.”

Re-reading portions of Kennedy’s Profiles in Courage, I cannot help but believe that Chief Justice Roberts, in considering his decision, confirmed to his colleagues as well as both political parties the meaning of courage.

“…courage,” Kennedy writes, “like political motivations, is frequently misunderstood. Some enjoy the excitement of its battles, but fail to note the implications of its consequences. Some admire its virtues in other men and other times, but fail to comprehend its current potentialities.”

What causes some individuals to act in such a way? Kennedy asks. Because “each one’s need to maintain his own respect for himself was more important to him than his popularity with others – because his desire to win or maintain a reputation for integrity and courage was stronger than his desire to maintain his office – because his conscience, his personal standard of ethics, his integrity, or morality, call it what you will – was stronger than the pressures of public disapproval…”

“…nine years in Congress,” Kennedy adds, “have taught me the wisdom of Lincoln’s words: ‘There are few things wholly evil or wholly good. Almost everything, especially of Government policy, is an inseparable compound of the two, so that our best judgment of the preponderance between them is continually demanded.”

Roberts’ decision is a landmark precisely because he has chosen statesmanship over partisanship. The question for elected officials who wish to lead could not be more urgent: Are they willing to demonstrate a similar sense of statesmanship, and if so, when will we see it?

Comments