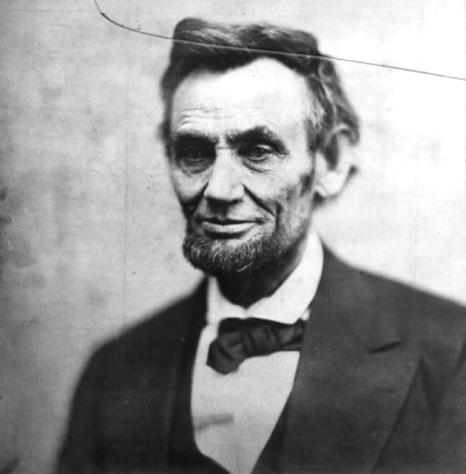

I’m always amazed at events honoring the day a renowned individual died versus celebrating what he or she stood for while they were alive. Certainly, such is the case with Abraham Lincoln who died at the hands of an assassin 150 years ago this month. There is, however, little doubt that Lincoln, although frequently referenced as our greatest president, was not held in similar esteem during his tenure as our 16th president.

In a book I regularly revisit, Lincoln on Leadership (1992), Donald T. Phillips notes, “Abraham Lincoln was slandered, libeled, and hated perhaps more intensely than any man ever to run for the nation’s highest office… He was publicly called just about every name imaginable by the press of the day, including a grotesque baboon, a third-rate country lawyer… a course vulgar joker, a dictator, an ape, a buffoon, and others. The Illinois State Register labeled him ‘the craftiest and most dishonest politician that ever disgraced an office in America.’ ”

Nonetheless, what makes Lincoln truly great in the long reflection of his actions, and words was his ability to face the greatest moral crisis of his time, slavery, with courage, compassion and considerable leadership. Despite the bloodiest and costliest war that almost permanently divided the country, Lincoln persevered in abolishing slavery, and reuniting the Union in words that have not only become iconic, but reflect the character of a man who worked tirelessly for harmony.

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

However, William Lee Miller’s book, Lincoln’s Virtues, An Ethical Biography (2002), is full of stories that attest to the man’s moral sense long before that great Civil War.

In 1850, Lincoln was asked to deliver a eulogy for President Zachary Taylor, a man and a president not well regarded by most. “Lincoln had to scratch a bit to find much to say about the virtues of Zachary Taylor,” Miller writes. “He was reduced to praising Taylor for his ‘sterling, but unobtrusive, qualities.’ ‘His rarest military trait,’ Lincoln the eulogist would say of General Taylor, was that he ‘was a combination of negatives – absence of excitement and absence of fear. He could not be flurried and he could not be scared…’

“But there is nevertheless in Lincoln’s eulogy of Taylor one passage that does reveal something about the virtues of the eulogist. One way or another, it is significant what we select to praise in others.

“Lincoln said of Taylor: ‘[H]e pursued no man with revenge.’ Then he dramatized an incident involving ‘the gallant and now lamented Gen. Worth.’ who, when a colonel, had been so offended by a decision against him by his superior General Taylor as to leave the army in Mexico and to tender his resignation to army authorities in Washington. ‘It is said, that in his passionate feeling,’ reported Lincoln, ‘he hesitated not to speak harshly and disparagingly of Gen. Taylor,’ and that as a respected officer his word carried weight. An unexpected turn in the war then brought the prospect of what would be the Battle of Monterey, and Worth was now ‘deeply mortified’ at being absent and seeing his laurels wither away. The government ‘both wisely and generously,’ Lincoln said, declined Worth’s resignation and returned him to General Taylor’s command.

“ ‘Then came Gen. Taylor’s opportunity for revenge.’ But of course he did not take it. Instead of placing Worth so that ‘his name would scarcely be noted in the report,’ Taylor, feeling that ‘it was generous to allow him, then and there, to retrieve his secret loss,’ assigned him ‘what was, par excellence, the post of honor,’ and Worth went on to glory.

“The selecting of that story tells as much about the eulogist as about the eulogy – magnanimity [considerate, forgiving, selfless], would, in time, be one of Lincoln’s prime virtues.”

Lincoln would again demonstrate that consideration when, after much disagreement between himself and Salmon P. Chase, his secretary of the Treasury, he accepted Chase’s resignation. Thinking that his career in public service had ended, Chase was surprised to learn that Lincoln had appointed him to be the new chief justice of the Supreme Court. Facing protests, Lincoln publicly responded:

“Chase is a very able man. He is a very ambitious man and I think on the subject of the presidency a little insane. He has not always behaved very well lately and people say to me, ‘now is the time to crush him out.’ Well, I’m not in favor of crushing anybody out! If there is anything that a man can do and do it well, I say let him do it. Give him a chance.”

Speaking on slavery and religion, Lincoln summoned words that appear appropriate in today’s Washington where we see the political fight brought in the name of “religious freedom.”

“I am not much of a judge of religion,” Lincoln said, “but, in my opinion, the religion that sets men to rebel and fight against their government, because, as they think, that government does not sufficiently help some men to eat their bread in the sweat of other men’s faces, is not the sort of religion upon which people get to heaven.”

While I cannot deny those who favor the ritual of remembering the day Lincoln died, I’m more interested in how the man lived and what he stood for.

Comments