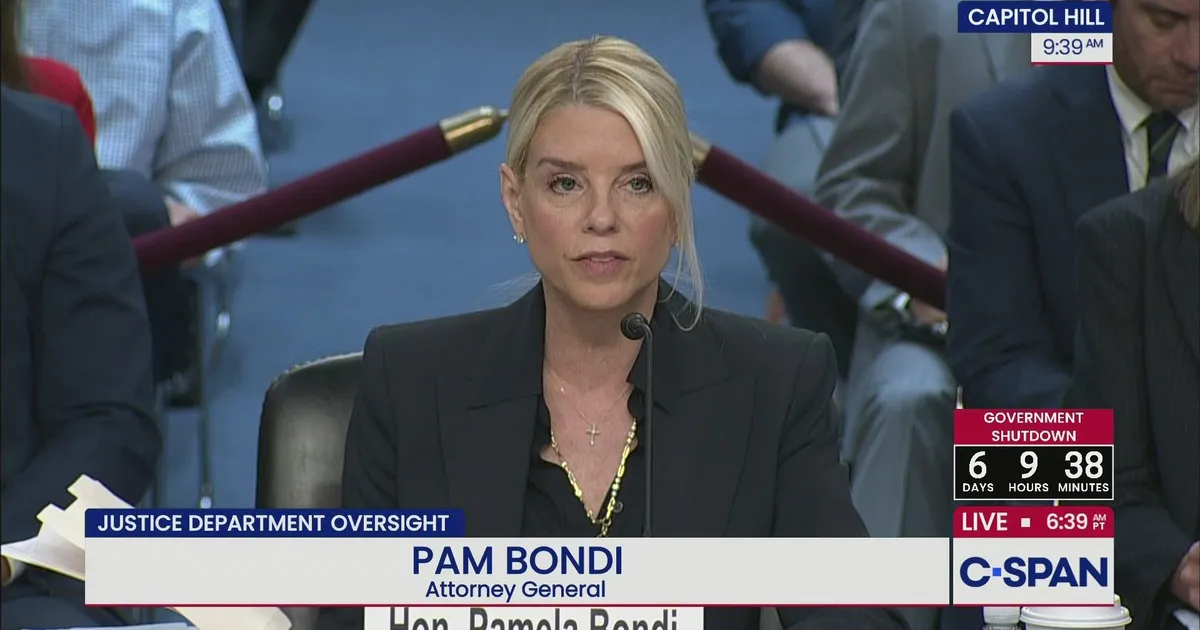

On October 7, 2025, Pam Bondi, the nation’s chief law enforcement officer, appeared before a Senate oversight committee and refused to answer question after question, so many, in fact, that committee member Adam Schiff was compelled to read them aloud. It was an extraordinary moment, not of legal restraint or principled caution, but of open arrogance, an unmistakable display of contempt for the Senate’s constitutional duty of oversight by the very official charged with defending the rule of law.

The Senate’s oversight role is not ceremonial. It is a constitutional and ethical obligation—one of the few mechanisms by which the legislative branch can test power, demand accountability, and ensure that the executive does not operate beyond public scrutiny. Oversight is how democracy asks its hardest questions out loud. When an Attorney General appears before a bipartisan oversight committee and responds not with reasoned explanation but with belligerence, evasion, and contempt, the issue ceases to be partisan disagreement. It becomes institutional defiance. (Here is the full committee hearing as recorded by CSPAN.)

Oversight depends on good faith. It rests on the expectation that public officials understand they serve the public through the law, not above it. Bondi’s refusals were not grounded in narrowly drawn claims of executive privilege or careful legal boundaries. They were dismissive rejections—signals that the questions themselves were illegitimate, that the Senate’s role was optional, and that accountability was an inconvenience rather than a duty.

This is not the first time an Attorney General has faced oversight scrutiny. History offers no shortage of uncomfortable hearings: Eric Holder over Fast and Furious, William Barr over the Mueller Report, Janet Reno during Waco. But even at their most contentious, those confrontations acknowledged the legitimacy of the process itself.

What made Bondi’s performance different was not disagreement, but disregard. Oversight was treated not as a constitutional necessity, but as an annoyance, one not only to be mocked but also used to make personal attacks against committee members.

Ethics in public life is not defined by how cleverly one avoids violating the law, but by whether one honors the institutions that give the law its meaning. A Justice Department that answers only to itself is not strong; it is unaccountable. And when its leader treats congressional oversight as an annoyance rather than an obligation, the harm extends far beyond a single hearing—it sends a dangerous message: that power need not explain itself, and accountability is optional.

The most troubling aspect of the hearing was not the refusal to answer, but the confidence with which it was delivered, the certainty that there would be no consequence. And she is likely correct.

Congress possesses tools to respond: subpoenas, contempt proceedings, and judicial enforcement. But they are rarely used with seriousness when executive officials stonewall. In practice, oversight too often ends with frustrated senators, a transcript for the record, and a public already exhausted by dysfunction.

The lesson: power learns quickly when resistance carries no cost.

Democracy rarely collapses in a single, dramatic moment. More often, it erodes quietly when constitutional duties are dismissed as inconveniences, and the institutions meant to restrain power choose accommodation over insistence. The wearing away is gradual, even civil in tone, but its danger lies precisely in how easily it becomes normalized.

The Senate asked the Attorney General questions on behalf of the public.

The Attorney General refused to answer them.

That imbalance—more than any single hearing, more than any single official—should concern anyone who still believes ethics are more than a talking point, and that accountability is not optional, even at the very top of the Department of Justice.

Comments