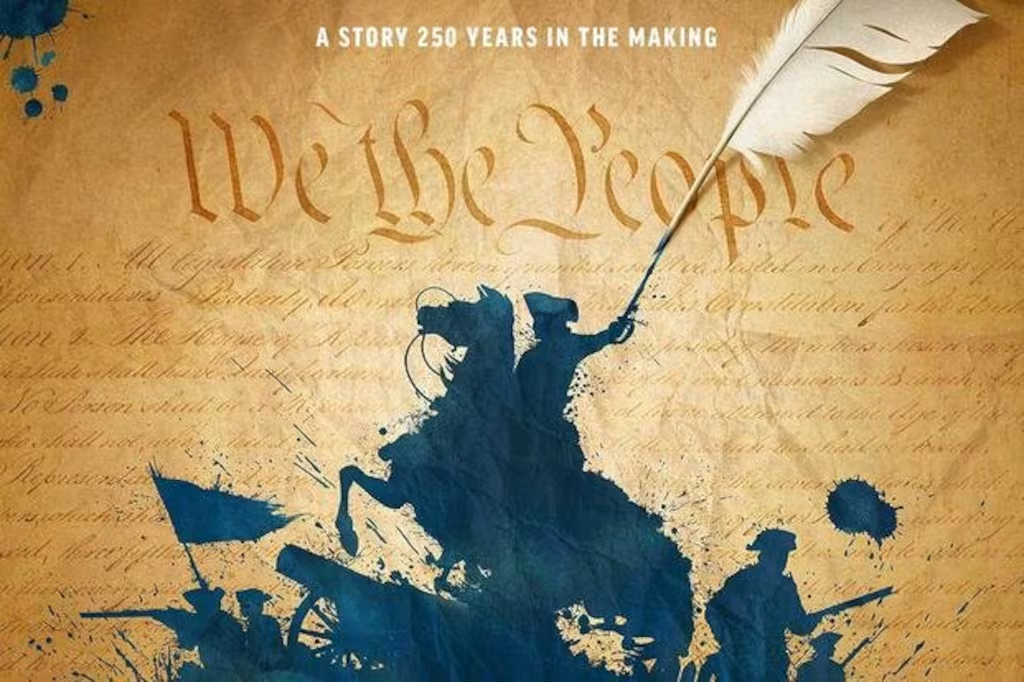

We toss the word “sacred” around as if it were a mood, something reserved for private faith. But in public life, “sacred” has a harder meaning. It names the few things a free society cannot afford to treat as negotiable.

Ken Burns’ The American Revolution includes an episode titled “The Most Sacred Thing.” Even without quoting a line of dialogue, that phrase lands like a challenge. Not a nostalgic salute to heroic paintings, but a question aimed straight at us: What, exactly, must remain untouchable if we want self-government to survive?

A republic can tolerate a lot. It can endure bad manners, overheated rhetoric, flawed candidates, even seasons of cynicism. What it cannot endure is the steady erosion of the things that make public life trustworthy. Once trust collapses, everything becomes raw power. Every dispute becomes existential. Every election becomes a fight to the death. And the nation’s moral vocabulary shrinks to one word: win.

So what belongs in the category of “most sacred” in civic life?

Start with truth—not as a slogan, but as a discipline. In a healthy democracy, truth is not what helps my side today; it’s what is true whether it helps me or hurts me. Truth is the common ground under our feet. When it becomes optional, the country loses its footing. We don’t merely disagree; we drift into separate realities. And when citizens can no longer agree on what happened, they can’t argue responsibly about what to do next.

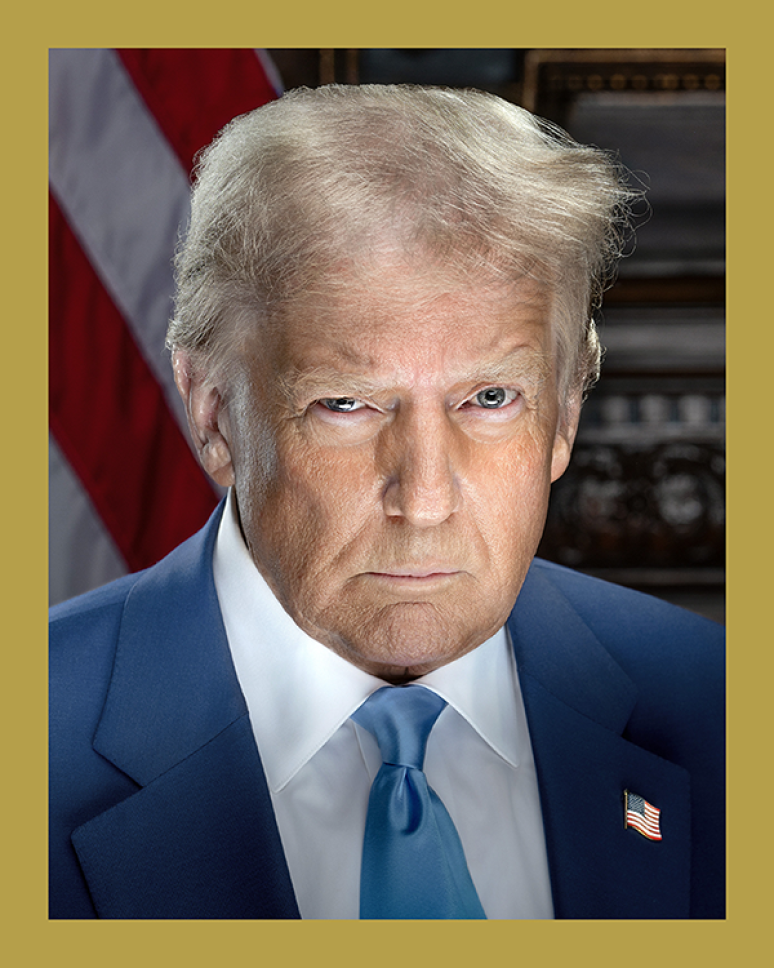

Then there are elections—not simply as outcomes, but as a shared covenant. Elections are the way we settle conflict without violence. They are the ritual by which rivals agree to live together after the votes are counted. If we treat elections as legitimate only when our side wins, we aren’t defending democracy; we’re using it.

Closely tied to that are courts—not as partisan prizes, but as the institutional embodiment of restraint. Courts exist to say: “You don’t get to do everything you want, even if you have the votes, even if you’re angry, even if you’re sure.” A nation that turns judges into mere extensions of political will is a nation dissolving the boundary between law and power.

Add oaths—because oaths are public promises that bind us to something larger than appetite and ambition. When an oath is treated as ceremonial theater, public service becomes performance. But when an oath is taken seriously, it is a reminder that office is not ownership. The job is stewardship.

And then there is the peaceful transfer of power, perhaps the most fragile miracle of all. It is civilization in miniature: the willingness to lose and still accept the rules, the willingness to hand the keys to a rival because the country is not a personal possession. Without peaceful transfer, politics becomes a permanent emergency—and emergencies are where liberty is most easily traded away.

Finally, there is restraint—the virtue we praise least and need most. Restraint is the decision not to weaponize every advantage, not to exploit every loophole, not to turn every disagreement into humiliation. Restraint is what makes room for tomorrow.

“The most sacred thing,” then, is not a symbol. It is a standard. It is the shared commitment that truth matters, elections matter, courts matter, oaths matter, peaceful transfer matters, and that power must be restrained because human beings are not angels.

If we want to remain a free people, we have to treat certain civic practices the way we treat sacred objects: not because they are delicate, but because without them, the whole house comes down.

Comments