Clarence Darrow spent his career standing next to people most of the country didn’t want to see.

Darrow, the legendary Chicago defense lawyer behind the Scopes “Monkey” Trial and the Leopold and Loeb case, didn’t defend clients because they were popular; he defended them because he believed the measure of a nation is how it treats the powerless. His deepest fear was not just “bad leaders,” but a public that stops asking questions. The issue now is whether we still have the courage to think for ourselves in a culture that rewards anger and obedience.

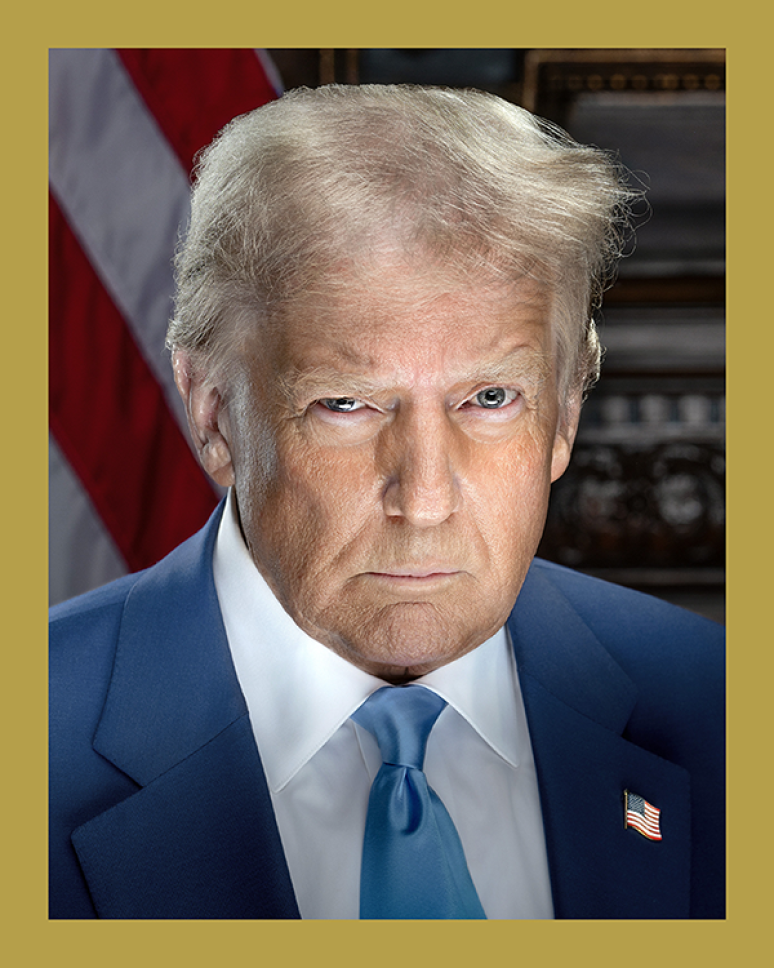

Autocracy doesn’t begin with tanks in the streets. It begins when citizens quietly hand over their judgment to someone who promises certainty: Trust me, and I’ll take away your doubts. I’ll tell you who’s right, who’s wrong, and who’s to blame. That can sound comforting—but it comes at the cost of our own responsibility to think and judge for ourselves.

In the Scopes trial, Darrow wasn’t just arguing about evolution; he was defending the right to think. Once you punish people for asking questions, you’re not protecting faith or tradition. You’re training a community to surrender its mind. That is the soil where autocracy grows.

Authoritarians always need an enemy—immigrants, judges, journalists, teachers, “the other party.” The point is not truth; the point is resentment. Convince enough people that someone out there is destroying their way of life, and you don’t have to answer hard questions about your own conduct. You just keep pointing, accusing, and dividing.

Darrow’s courtroom practice moved in the opposite direction. He stood beside the despised and said, in effect, This person still has rights. This person is still a human being. That was more than a legal strategy; it was an ethical line in the sand. The moment we decide that some people are beneath rights, we’ve accepted a framework ready-made for autocracy.

He also understood that our institutions are imperfect—juries swayed by prejudice, courts influenced by money, laws bent to favor those already in power. That is exactly why he would resist giving even more deference to any leader who demands loyalty first and questions later.

When a politician insists that he alone speaks for “the people,” that critics are “enemies,” that the press cannot be trusted, that courts are corrupt when they rule against him, and that elections are valid only if he wins, we are no longer debating policy. We are watching the foundations of a constitutional democracy being chipped away.

Thinking is a moral duty. In a free society, citizens are not spectators. Democracy depends on individual acts of judgment: checking facts, weighing evidence, listening to people we disagree with, and being willing to change our minds when the facts change.

Doubt is not disloyalty. Darrow believed doubt was the beginning of wisdom. Political movements that treat doubt as betrayal are not asking for support; they are demanding submission. Empathy is a safeguard. Autocracy runs on dehumanization. It needs us to believe that some neighbors are less deserving, less American, less real.

Citizens of good faith will disagree about policy. But there ought to be a baseline we still share: that no leader is above the law; that elections cannot be legitimate if only one outcome is acceptable; and that public office is not a personal weapon to use against critics.

Persuading Americans in this moment doesn’t mean shouting louder or matching contempt with contempt. Darrow’s example points to something quieter and harder: appeal to conscience. Ask people, calmly and directly:

Should any leader be beyond accountability?

Should loyalty to a person matter more than loyalty to the Constitution?

If the tactics you defend today were used against you tomorrow, would they still be acceptable?

Autocracy is not our fate. It is a series of choices—some loud, most quiet—about what we’re willing to overlook and whom we are willing to follow. The question Darrow kept placing before juries is the same question facing the country now:

When it’s your turn to decide, will you choose fear and obedience, or conscience and responsibility?

Comments