The CBS news show “60 Minutes” ran two compelling stories last Sunday (May 4). I’m not sure if the producers were aware just how similar, yet ethically different the first two stories were.

Both segments talked about mistakes that were made. Both discussed the tragic, personal costs of those mistakes. However, that is where one story took a “right” turn.

James Woodard was convicted of murdering his girlfriend and sent to prison in 1981. For nearly 30 years, Woodard wrote letters and filed motions protesting his innocence. No one granted him a hearing until last year when Craig Watkins became the new district attorney in Dallas, Texas and began looking into a backlog of previous convictions with certain irregularities.

“We have a responsibility to go back and right the wrongs of the past and free the innocent,” Watkins told reporter Scott Pelley.

After Watkins’ office presented evidence that the prosecutors failed to tell the defense and the jury that Woodard’s girlfriend had been in the company of another man the night of her death along with DNA evidence proving Woodard’s innocence, James Woodard was released after serving nearly 27 years in prison.

Then, in a Dallas courtroom, in front of a gallery of spectators, a district judge, as well as the innocent Woodard, Dallas District Attorney Craig Watkins did one more thing.

“Mr. Woodard,” Watkins said, “we’d like to apologize to you. Not only on the part of the district attorney’s office for the state of Texas, but for the failures of the criminal justice system throughout this country.”

In six words, District Attorney Craig Watkins acknowledged responsibility for a miscarriage of justice, expressed genuine remorse, and then demonstrated a sincere commitment not to let it happen again by pursuing similar cases.

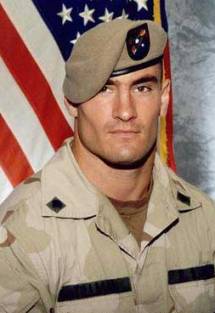

The second story examined the death of football star Pat Tillman from “friendly fire” in Afghanistan.

What makes Tillman’s death all the more tragic, is that the military had told the family as well as the media that their son had died heroically, charging up a hill, saving the lives of his fellow Army Rangers.

And it was all false.

A month after his death, the Army released another report stating that Tillman had been killed by his own men in a tragic mistake.

“…they could’ve said anything,” Tillman’s mother, Mary, told reporter Katie Couric. “But they made up a story.”

Mary Tillman began her own investigation into her son’s death which led to the discovery of inconsistencies in the official military account and ultimately, the truth – that her son Pat had accidentally been killed by his own men. But that didn’t trouble her as much as the way military had handled the matter.

“…the story itself seemed so contrived,” Mary Tillman said. “When we heard it was a friendly fire, I felt terrible for these soldiers.”

“We all knew,” Donald Lee, a soldier in Tillman’s unit said. “I just don’t understand why nobody, you know, told Pat’s parents…”

Couric asked Secretary of the Army Pete Geren how this could have happened.

“Well, that’s one of the questions that we will never completely answer,” Geren said. “There are so many mistakes. So many things that happened. If you add them all together, it certainly calls into question the credibility of those who handled this. And raises the kind of questions that Ms. Tillman raises. I don’t blame her for that. And I don’t expect her ever to believe us… But, we’ve had seven investigations and they have all concluded that there was no deceit, no intentional deceit, no cover up.”

And no apology.

And that is the ethical difference between these two stories.

In all their efforts to make things right, Secretary Geren never offered an apology to Pat Tillman’s family and to the American people, for that matter. The secretary of the Army seems sadly unaware that it is a lack of character on his part as well as the military that calls into question the credibility of those who handled the death of Pat Tillman. We saw the same thing happen a year earlier when the military concocted a “hero story” surrounding the capture and rescue of Army PVC Jessica Lynch in Iraq.

“They took the honor away from, you know, what we were doing by lying to his family,” Donald Lee said of Tillman’s death.

Nothing is going to bring back Pat Tillman. And no one can give back the almost thirty years lost behind bars to James Woodard, but an apology is a beginning. A sincere apology acknowledges responsibility for the wrong action. It also allows the person offering the apology to demonstrate genuine regret which can lead to a meaningful change in behavior; a change that the military desperately needs to regain its credibility.

Does an apology make a difference? Reporter Scott Pelley asked James Woodard if it was worth the wait.

“For so many years everyone told me, ‘Well hey, you’re guilty.’ Just to hear someone admit that they were wrong, they did me wrong. …It was well worth the wait.”

Comments