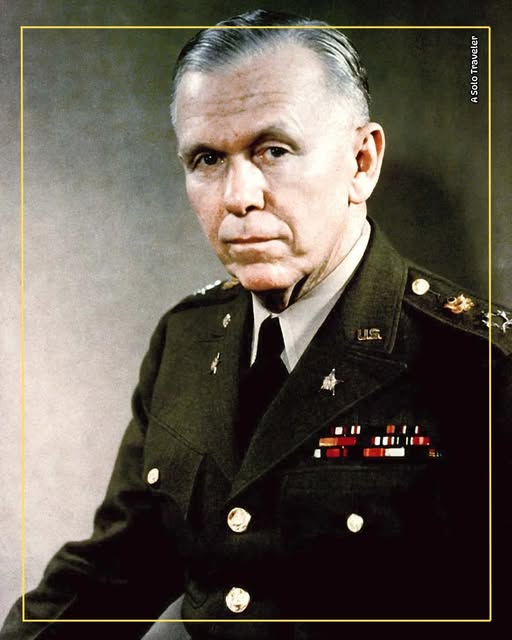

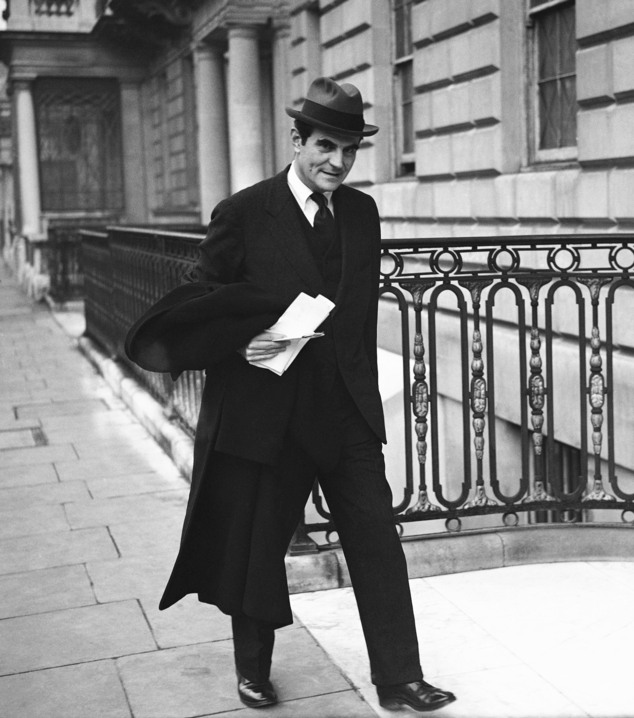

AP file photo

At a small private cemetery located on the grounds of St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire there stands a striking granite headstone marking the grave-site of a man who not only attended and taught history at the exclusive prep-school, but served as the state’s governor and later as U.S. ambassador to England.

Carved into the granite are words that best describe the legacy of John Gilbert Winant.

“Doing the day’s work day by day, doing a little, adding a little, broadening our bases wanting not only for ourselves but for others also, a fairer chance for all people everywhere. Forever moving forward, always remembering that it is the things of the spirit that in the end prevail. That caring counts and that where there is no vision the people perish. That hope and faith count and that without charity, there can be nothing good. That having dared to live dangerously, and in believing in the inherent goodness of man, we can stride forward into the unknown with growing confidence.”

Working tirelessly, along with broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow and American Special Envoy Averell Harriman to urge Franklin Roosevelt to enter the war before the will and resources of England were exhausted, Winant was with Winston Churchill at his country estate at Chequers on December 7, 1941. Intelligence sources had just reported that two Japanese convoys, 63 transports and warships had been sighted off Cambodia. Winant had found Churchill pacing around consumed by the fear that Japan was readying an attack on Siam or British territory.

“If they declare war on you,” Churchill told the American ambassador, “we shall declare war on them within the hour.” The prime minister then asked Winant, “If they declare war on us, will you declare war on them?”

“I can’t answer that,” Winant said. “Only the Congress has the right to declare war…”

That night at dinner, Churchill asked his butler to bring a radio to the table. The evening’s music was interrupted by the announcement of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

In her enlightening chronicle, Citizens of London, Lynne Olson describes the scene.

“With that, Churchill was on his feet and heading toward the door, exclaiming, ‘We shall declare war on Japan!’

“Throwing his napkin on the table, Winant jumped up and ran after him. ‘Good God, you can’t declare war on a radio announcement!”

“Churchill stopped and, looking at him quizzically, asked, ‘What shall I do?’ ”

“I will call up the President by telephone,” Winant said, “and ask him what the facts are.”

After Roosevelt confirmed the information, the president added, “We are all in the same boat now.”

“The prime minister,” Olson writes, “was euphoric, and so were his two American guests.”

However, in his memoirs, Churchill modified his original thoughts on the scene, noting, “They did not wail or lament that their country was at war… In fact, one might almost have thought that they had been delivered from a long pain.”

“That night,” Olson adds, “[Churchill] wrote [that] he ‘slept the sleep of the saved and thankful,’ quite convinced now that ‘we had won the war. England would live.”

In 1947, Winant was only the second (and last) American citizen, after General Dwight Eisenhower, to be made an honorary member of the British Order of Merit.

Within his own state, Governor Winant was known for his personal outreach to ordinary citizens during the Great Depression.

As noted in a recent story in The Concord Monitor (Mar. 31), “John Milne, a local historian and former newspaper editor, relayed a story via email that reflected what made Winant tick.

“It wasn’t politics or his party affiliation.

“It was something else.

“ ‘I’ve always thought the key to Winant was a job interview he conducted as head of Social Security with Tom Eliot, a New Dealer who later became a member of Congress,’ Milne wrote to me. ‘Winant asked Eliot what he thought was the most important characteristic of a politician. Eliot, taken aback, sputtered that he thought it was intelligence and integrity. No. It was kindness.’

“That led to the stories of Governor Winant handing money to victims of the Depression. Right near his downtown office.

“ ‘They’d be sitting on the walls of the state house,’ Shurtleff told me. ‘He would go over and talk to them and give them 50 cents so they could get something to eat and get a place to stay that night. He had that common touch.’ ”

As New Hampshire Professor Stephen Ambra aptly points out, “Winant also defines the difference between statesman and politician, a person of courage who was motivated by ethical values over party politics.”

Comments