According to a survey by the Gallup organization (Aug. 2013), “Most Americans (80 percent) believe that today’s schools should teach… critical thinking… to children.”

“Critical thinking,” as defined by The Critical Thinking Community, “is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.”

Much like an ethical decision-maker utilizes fairness, a critical thinker applies the notions of equity, openness and consistency. However, fairness, in its purest sense, is one of the most elusive of ethical values since, in most cases, stakeholders with opposing interests strongly disagree on what is fair.

According to Richard Paul and Linda Elder, from their bookThe Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, (2008), “Everyone thinks; it is our nature to do so. But much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uninformed or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and that of what we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Shoddy thinking is costly, both in money and in quality of life. Excellence in thought, however, must be systematically cultivated.”

So who is a well cultivated thinker? Paul and Elder define such an individual as someone who:

- raises vital questions and problems, formulating them clearly and precisely;

- gathers and assesses relevant information, using abstract ideas to interpret it effectively comes to well-reasoned conclusions and solutions, testing them against relevant criteria and standards;

- thinks open-mindedly within alternative systems of thought, recognizing and assessing, as need be, their assumptions, implications, and practical consequences; and

- communicates effectively with others in figuring out solutions to complex problems.

You might think that Supreme Court Justices would clearly measure up to these qualities when it comes to making decisions that affect us all, and for the most part they do… within the context of their ideological beliefs – meaning, conservatives generally support conservative issues and liberals support liberal issues.

However, do justices display bias when it comes to an issue they all generally agree upon such as free speech?

Here’s where it gets interesting.

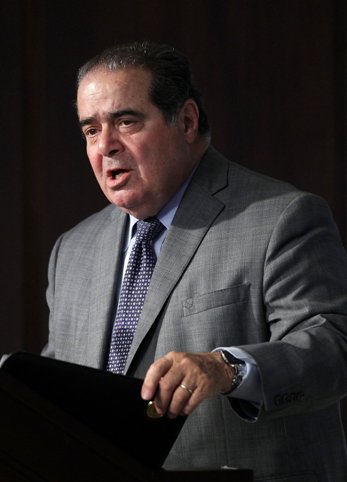

As reported in The New York Times (May 5), “Justice Antonin Scalia is known as a consistent and principled defender of free speech rights.

“It pained him, he has said, when he voted to strike down a law making flag burning a crime. ‘If it was up to me, if I were king,’ he said, ‘I would take scruffy, bearded, sandal-wearing idiots who burn the flag, and I would put them in jail.’ But the First Amendment stopped him.

“That is a powerful example of constitutional principles overcoming personal preferences. But it turns out to be an outlier. In cases raising First Amendment claims, a new study found, Justice Scalia voted to uphold the free speech rights of conservative speakers at more than triple the rate of liberal ones. In 161 cases from 1986, when he joined the court, to 2011, he voted in favor of conservative speakers 65 percent of the time and liberal ones 21 percent.”

The study, conducted by Lee Epstein, a political scientist and law professor, considered 4,519 votes in 516 cases from 1953 to 2011.

“While liberal justices are over all more supportive of free speech claims than conservative justices,” the study found, “the votes of both liberal and conservative justices tend to reflect their preferences toward the ideological groupings of the speaker.”

“Social science calls this kind of thing ‘in-group bias,’ The Times says. “The impact of such bias on judicial behavior has not been explored in much detail, though earlier studies have found that female appeals court judges are more likely to vote for plaintiffs in sexual harassment and sex discrimination suits.

“The findings are a twist on the comment by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. that the First Amendment protects ‘freedom for the thought that we hate.’ On the Supreme Court, the First Amendment appears to protect freedom for the thought of people we like.”

But here’s yet another interesting twist on the issue of bias.

According to the Gallup Organization’s Barry Conchie (June 4, 2013), “Feeling that you’re right or wrong doesn’t always correlate with being right or wrong. Certainty in these things is a very dangerous feeling.”

Conchie, a senior scientist at Gallup and coauthor of Strengths Based on Leadership, suggests “It would be far better to know where you might be wrong — and to recognize why.

“Conchie says there are a handful of cognitive flaws that everyone — executives included — are particularly apt to fall prey to. Among them are:

“Confirmation bias: We tend to search for things that confirm what we believe and ignore things that don’t.

“Overconfidence effect: Our confidence in our judgment is generally higher than the actual accuracy of that judgment.

“Hindsight bias: This is the feeling that we “knew it all along” — that our successes or failures were more predictable before they happened than they actually were.

“Bias for action: We tend to want to act or make decisions before we analyze or plan.”

While I would generally exclude the fourth flaw when it comes to Supreme Court justices, one could certainly make a case that the “overconfidence effect” played no small part in the Citizens United decision.

Conchie recommends that we all “be aware of what and how [we] are thinking – and recognize that [we] may be wrong even when [our] brain is telling [us we’re] right. ‘It’s so easy to make cognitive mistakes and so hard to realize you’re doing it,’ says Conchie. ‘But that’s not a new idea – [17th century Dutch philosopher] Baruch Spinoza laid to rest the idea that humans are rational 450 years ago. But it’s taken us a while to come around to it.’ “

Comments