“Everybody does it.” “I hardly ever lie.”

I collect ‘em, like baseball cards.

“You don’t understand, Jim,” the owner of a large company once told me, “it’s just industry practice. We don’t want to do these things, but if we want to operate from a level playing field, sometimes we have to [be unethical].”

Last October, Lehman Brothers Chief Dick Fuld told Congress: “I wake up every single night thinking, ‘What could I have done differently? At the time, I made those decisions with the information I had.”

Bear Stearns Chief Alan Schwartz said “If I’d have known exactly the forces that were coming, what actions could we have taken beforehand to have avoided this situation?’ And I just simply have not been able to come up with anything … that would have made a difference to the situation that we faced.”

Although Schwartz’s predecessor, James Cayne, never had to testify before Congress, he told financial writer William Cohan that before resigning, “there was a period of not seeing the light at the end of the tunnel …. I wasn’t good enough to tell you what was going to happen.”

“Now, wait just a minute here,” Cohan writes in the New York Times (Mar. 12). “Can it possibly be true that veteran Wall Street executives like Messrs. Cayne, Schwartz and Fuld – who were paid an estimated $128 million, $117 million and at least $350 million, respectively, in the five years before their businesses imploded — got all that money but were clueless about the risks they had exposed their firms to in the process?”

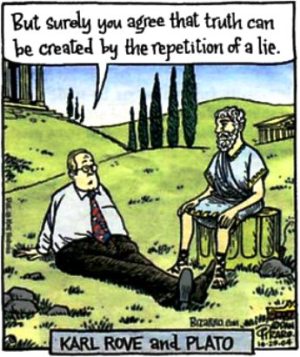

Explanations, justifications – they’re really all rationalizations for a great lack of ethical judgment. The fact is some people have gotten so used to justifying and rationalizing that they seem to have lost all sense of what the truth really is much less how their own integrity has been eroded in the process.

In a congressional committee hearing looking into the Enronscandal, North Dakota Senator Byron Dorgan challenged former CEO Jeff Skilling. Dorgan recalled a joke Skilling had once made comparing California to the Titanic.

“On the Titanic,” Dorgan said, “the captain went down with the ship. At Enron, it looks like the captain gave himself and other top executives bonuses, then lowered himself in the lifeboat and said, ‘Everything’s going to be fine.’”

“I think that’s a pretty bad analogy,” Skilling said. “I wasn’t on the Titanic. I got off in Ireland!”

Some of these executives seem more focused on mastering tricky wordplay than being accountable.

But the reality is this: if trust is critical to you with family, friends, co-workers; if honesty, integrity and responsibility are qualities that you count on, then we need to practice ethical values in everything we do, not just when it’s convenient.

In 1982, when several poisonings had been linked to Tylenol capsules, Johnson & Johnson Chairman James Burke called for the removal of all forms of Tylenol from every store in the country. Although Tylenol accounted for $100 million annually, Burke demonstrated through his decision-making process that the public’s safety was the company’s first priority.

“As I look back on Tylenol,” Burke told me, “I think that the only way we could have done what we did was to have all of the institutions that were affected by the Tylenol poisonings believe in us. And I want to emphasize, believe in US, the company. Whether it was the head of the FBI, FDA, or the people at the White House, there was no lack of trust about Johnson & Johnson. There was no thought that this was something that we were doing that was only in our own self-interest.”

If we are ever going to return to a higher standard of leadership, we need to understand that ethics is not about what we say or what we intend, it’s about what we do. And how we utilize our principles in small ways, as well as those that challenge the courage of our convictions, will, ultimately, determine the purpose and course of our lives.

Comments