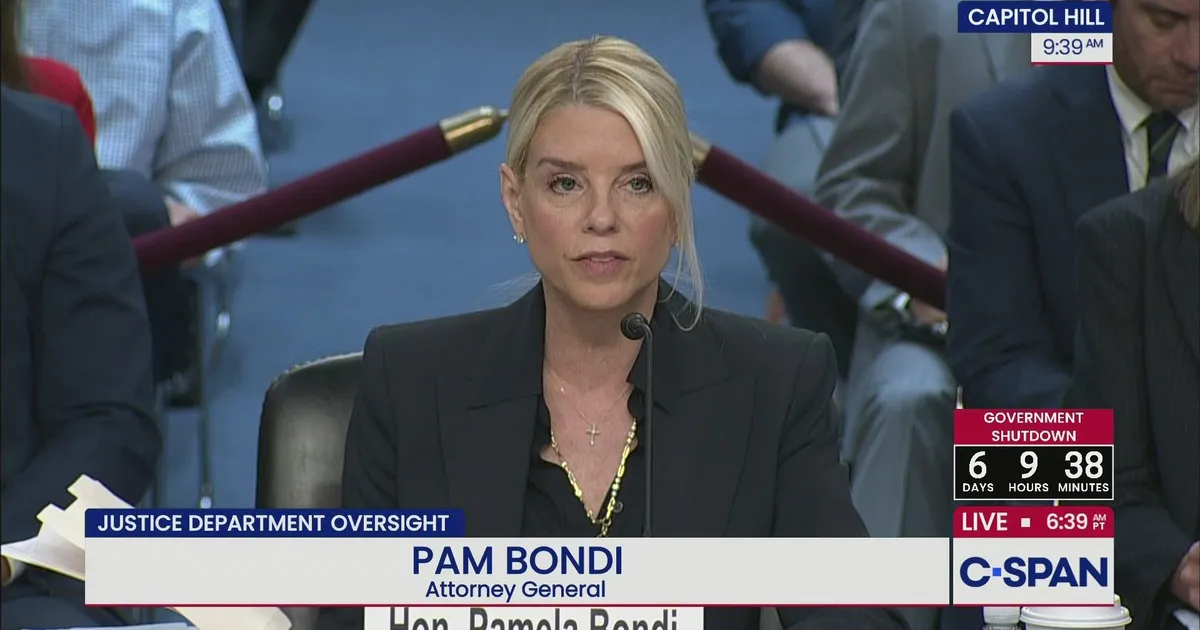

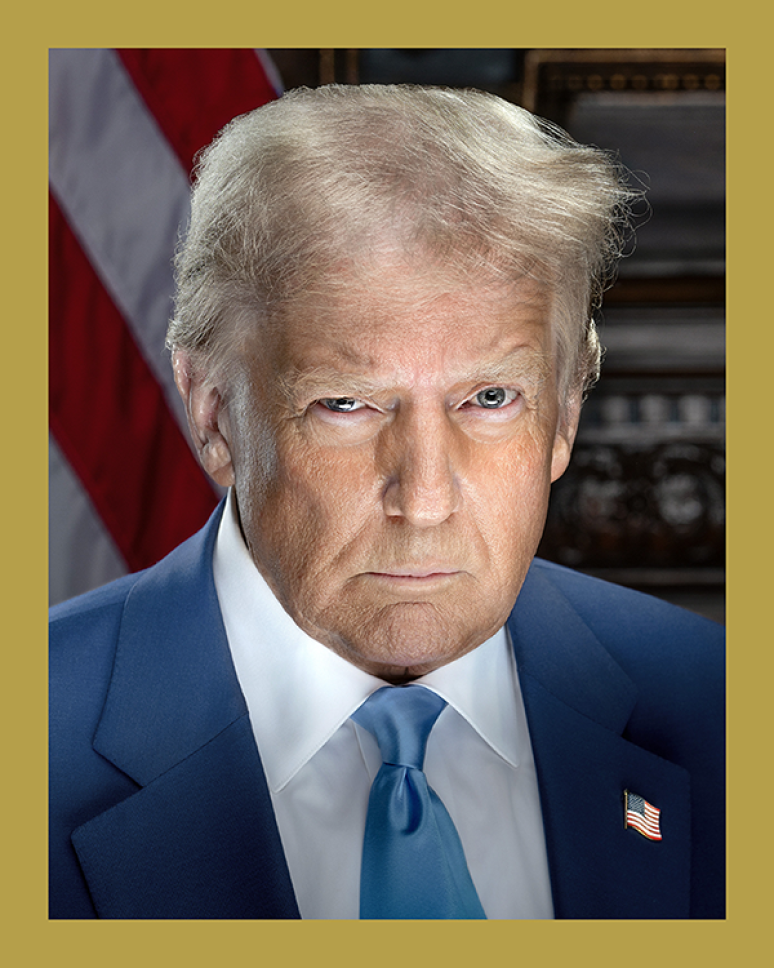

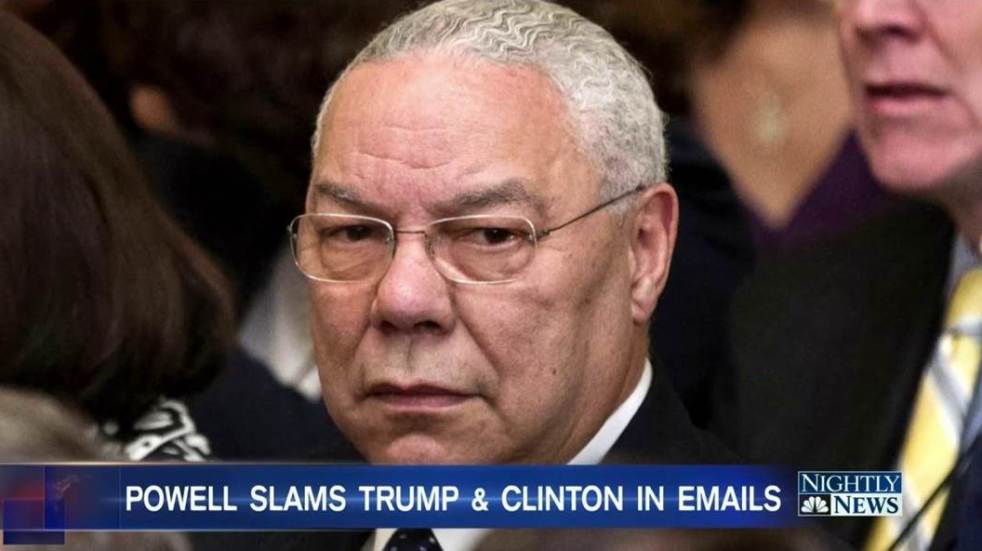

The publication of Colin Powell’s private opinions of both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump – obtained from hacked e-mails from the former secretary of state’s private e-mail account – is only the latest example of the thorny ethical issues that journalists and media organizations must navigate. In this new universe, everything that’s been hacked appears to be fair game after it’s been posted on the Internet.

It’s interesting to note that as I write about the issue of privacy, the Oliver Stone feature, Snowden, is being released around the country. The film has been characterized as a “fictionalized” account of the National Security Agency contractor – who is either a patriotic whistler-blower, or dispassionate traitor, depending on who you talk to – who willfully went around government higher-ups to disclose classified NSA information to several newspapers in 2013.

I’ve written about Snowden before, (Citizen Who? Mar. 5, 2015), where I don’t take lightly his actions in placing government secrets at risk by way of exposing illegal wiretapping practices by the NSA, especially when other options were available to him. Admittedly, over the past year, Snowden, who has made a number of appearances via satellite conferences, appears sincere in his concern about privacy in the U.S. But this is a story I will revisit in the future.

* *

In what were supposed to be private opinions in a series of e-mails, Colin Powell offers candid assessments of Hillary Clinton, Donald Trump and others. I’m not going to repeat them here. You can easily find them through any number of sources on the Internet. My focus is on the ethical implications of releasing such material.

Individual privacy is an important matter, whether you are talking about the NSA, a former government official like Powell or a private citizen. Without clear ethical guidelines, the media can literally rationalize whatever they wish in order to print, post, or publically reveal private or illicit information.

Professor Stephen Ambra, who teaches an intensive, week-long ethics class at The New Hampshire Technical Institute, writes: “If ‘secure e-mail’ is an oxymoron, then there is a little, or no reasonable expectation of privacy, regardless if the e-mail is from a public figure or a private individual.

“Clearly, news organization cannot – legally and ethically – engage in the theft of secure e-mail messages. But where is the line drawn between reporting the theft and revealing the contents of the stolen e-mails? How much of an accessory to theft is a news organization when it reports the contents? Are the contents newsworthy, in the time honored tradition of All the News That’s Fit to Print?”

These are just a few of the questions a responsible news organization needs to ask. It’s also why those same organizations need to recognize that journalism is a public trust. As such, journalists need to act responsibly in order to maintain a reputation of trust.

In an exclusive interview with former Navy SEAL “Mark Owen” — a pseudonym for the author who wrote the book, No Easy Day, about the killing of terrorist Osama bin Laden — CBS journalist Scott Pelley explained that while “Owen’s” real name had recently been revealed by several media sources, he would not take part in that disclosure.

It was an important moment for Pelley and an example to journalists in how to treat private information, and not engage in the rationalization, “everyone else has released the name.”

In Ethical Principles of Journalism, ethicist Michael Josephson explains that the purpose of journalism is about the “unselfish pursuit of three public service functions: 1. Teacher – informing us of things we ought to know to make us better citizens and persons; 2. Conscience – confronting us with opinions and facts which challenge us to live up to our values and beliefs; and 3. Watchdog – uncovering and exposing corruption, mismanagement, waste, hypocrisy and other forms of impropriety which threaten public interests.”

With this in mind, let’s take a closer look at the questions surrounding the release of former Secretary Powell’s private e-mails.

1) Do Powell’s private opinions of both Trump and Clinton inform us of things “to make us better citizens and persons”?

No.

2) Do Powell’s private opinions of Clinton and Trump “confront us with opinions and facts which challenge us to live up to our values and beliefs”?

While I have a great respect for Secretary Powell’s opinions, I have more than a reasonable amount of information about him through his public speeches and books. I really can’t make the case for bolstering my own values and beliefs by learning his private thoughts about the two candidates. My answer: no.

3) Does the release of Powell’s e-mails uncover and expose corruption or “other forms of impropriety which threaten public interests”?

No.

Josephson adds, “Journalists should demonstrate respect for human dignity, privacy, autonomy of others, and the right of self-determination by treating people with respect, courtesy and decency, and by providing information needed to make informed decisions.”

4) Does the release of Powell’s e-mails provide “information needed to make informed decisions”?

While Powell’s opinions may be of interest to many in the country, they are, in fact, not necessary to make an informed decision. Further, the publication of his private e-mails violates his right of self-determination.

Finally, there’s the aspect of how the e-mails were obtained.

Let’s be clear, no matter how you phrase it, “hacking” is stealing, period. And unless the information provided in stolen documents exposes past, present or future criminal activity, journalists must carefully consider how the information was obtained and for what purpose.

Last Monday (Sept. 12), on CBS This Morning, Secretary Powell was interviewed by the hosts, and, as expected, they asked his opinion of the current presidential race.

Always a respectable gentleman, Powell said, “There are elements in my party, the Republican Party, that show some level of intolerance that I don’t think is worthwhile for the party to demonstrate.”

In terms of which candidate he will support, Powell explained that he wanted to see how both candidates respond in the upcoming debates.

Out of respect, the media should have treated Powell with the same privacy and dignity reflected in his public response.

In the “Letters” section in last Friday’s New York Times (Sept. 15, on the website), one reader offered a succinct and clear-headed response:

“ ‘Powell’s Emails Show Scorn for Trump and Irritation at Clinton’ (front page, Sept. 15) raises troubling questions about journalistic ethics in an age of hacking. Colin Powell, a former secretary of state, retired from public service and returned to private life and should have been allowed to publicly comment on the current election if and when he wished. It is unclear that it was a matter of public interest to know Mr. Powell’s privately expressed opinions.

“True, the hacked information was online for all to see, and other outlets had covered the materials. But I hope that editors of The Times, a ‘paper of record’ that aspires to high ethical standards, debated in depth whether and what to publish.

“When prominent outlets publish hacked information, it spreads to a far wider audience, the hacking is legitimized and the hackers gain greater attention, likely encouraging further hacking.

“Leaks of information to which a person has access have their own ethical dilemmas, but hacks of private information are stealing and should be treated as such.”

Kai Thaler, Boston

In an e-mail to the Times’ Chairman and Publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr., I asked him to clarify the ethical decision-making that takes place regarding the issue of publishing stolen information. I will report further if and when I receive a response.

Ethics Professor Stephen Ambra offers a relevant postscript to this incident and the many more that are likely to follow.

“As self-appointed arbiters of truth, the ‘About’ DCLeaks [source of the Powell e-mails] statement is many things including chilling, provocative and audacious, with a touch of hubris. But, what sometimes takes historians decades to uncover – if ever, or fiction writers to conjure or conspiracy theorists to prophesize – may now, thanks to groups like DCLeaks, merge much more quickly the truth of events, almost in real time, what is believed to have occurred with what really did happen.”

Comments