After spending a week in Boston, I came away refreshed from tours of the Freedom Trail, the North Church, Boston’s original State House and Faneuil Hall, often referred to as The Cradle of Liberty.

Prior to the Revolutionary War, thousands stood in that great Hall to listen to the likes of Samuel Adams, his cousin John, and other “Sons of Liberty” as they debated Britain’s Sugar Tax, Stamp Act and, the tax that finally pushed the colonists over the edge, the new tax on tea in 1773.

What surprised me from the lecture, earnestly delivered by the National Park Ranger, were two things. First, the definition of Freedom and Liberty during revolutionary times meant the freedom to own slaves and that women were excluded from the political process.

The second was the fact that while issues were often fiercely debated, you saw and heard the individuals offering their opinions. The anonymity of social media was more than 200 years in the future. As such, the quality of the debaters rested, not only on reasoned arguments, but on the reputation of the individuals standing in front of you.

But look at that enormous mural behind the ranger at the front of the Hall.

Entitled, Webster’s Reply to Hayne, the mural illustrates Massachusetts Senator Daniel Webster concluding his debate with South Carolina’s Robert Y. Hayne. The debate that began six weeks earlier focused on a bill that would end the selling of cheap lands in the west. Merchants believed that such a sale would result in mill workers leaving New England, harming the textile industry.

However, the focal point of the vast painting is Webster’s impassioned argument.

“When Webster stepped up in the Senate chamber to reply on January 27, 1830,” the Park Service writes, “he defended both the Union and New England. During the course of the reply Webster defended his region. New England had begun the War of Independence and ultimately New England, he believed, would be the last shelter for liberty. “Liberty and Union, Now and Forever; One and Inseparable” echoed through the crowded chamber in his conclusion.”

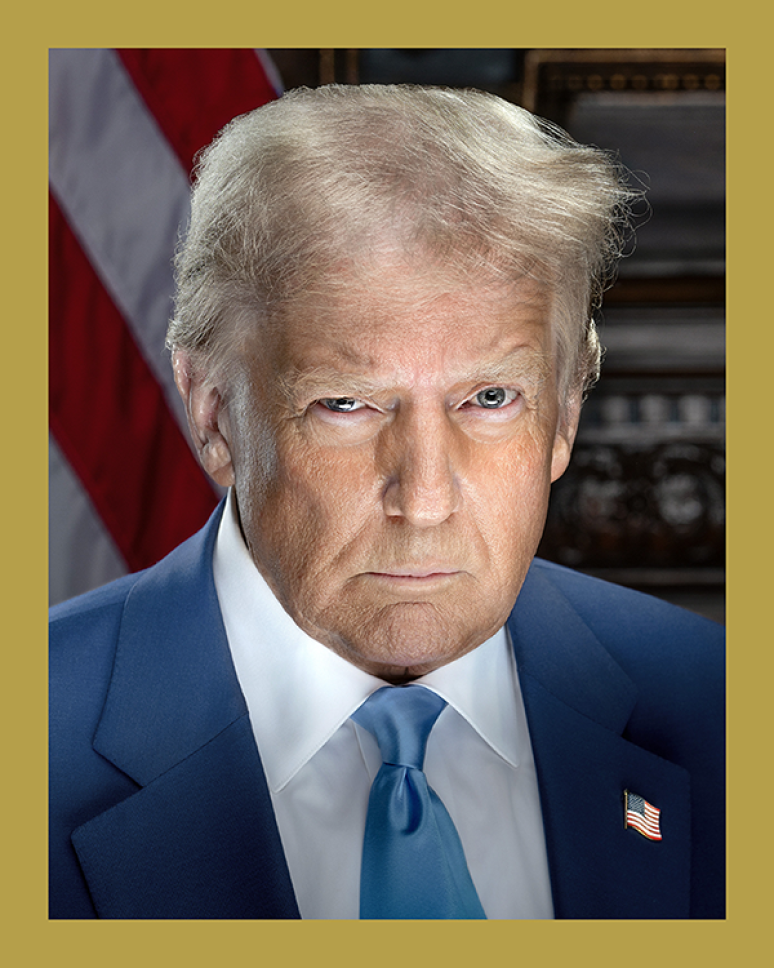

As the ranger finished his brief history, I wondered where that kind of passion, commitment, and fortitude is in the chambers of Washington today.

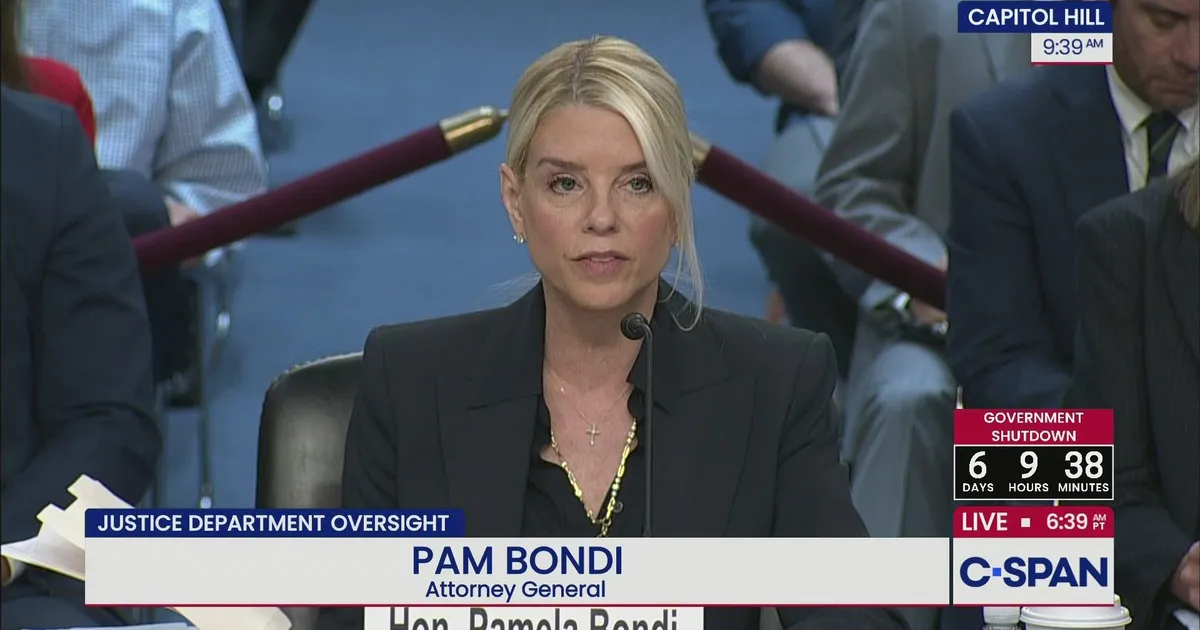

The last true example of Webster came from retiring Arizona Senator Jeff Flake during a commencement address to the Harvard Law class of 2018. (While I offer some key passages, it’s worth reading in its entirety):

“…with humility,” Flake began, “let me suggest that perhaps it is best to consider what I have to say today as something of a cautionary tale —

“- about the rule of law and its fragility;

“- about our democratic norms and how hard-won and vulnerable they are;

“- about the independence of our system of justice, and how critically important it is to safeguard it from malign actors who would casually destroy that independence for their own purposes and without a thought to the consequences;

“- about the crucial predicate for all of these cherished American values: Truth. Empirical, objective truth;

“- and lastly, about the necessity to defend these values and these institutions that you will soon inherit, even if that means sometimes standing alone, even if it means risking something important to you, maybe even your career. Because there are times when circumstances may call on you to risk your career in favor of your principles.

“But you — and your country — will be better for it. You can go elsewhere for a job, but you cannot go elsewhere for a soul. …

“Because we forget this fact far too often, and it bears repeating a thousand times, especially in times such as these: Values transcend politics. …

“The greatness of our system is that it is designed to be difficult, in order to force compromise. And when you honor the system, and seek to govern in good faith, the system works. …

“The values of the Enlightenment that led to the creation of this idea of America — this unique experiment in world history — are light years removed from the base, cruelly transactional brand of politics that in this moment some people mistakenly think is what it means to make America great.

“To be clear, we did not become great — and will never be great — by indulging and encouraging our very worst impulses. It doesn’t matter how many red caps you sell.

“The historian Jon Meacham, in his splendid new book, The Soul of America, reassures that history shows us that ‘we are frequently vulnerable to fear, bitterness, and strife.’ The good news, he says, ‘is that we have come through such darkness before.’ …

Looking at the young audience of future attorneys before him, Flake concluded, “…I urge you to challenge all of your assumptions, regularly. Recognize the good in your opponents. Apologize every now and then. Admit to mistakes. Forgive, and ask for forgiveness. Listen more. Speak up more, for politics sometimes keeps us silent when we should speak.”

Senator Flake gave that address just a short distance from Faneuil Hall.

Comments