In 1998, at the height of Independent Counsel Ken Starr’s investigation into President Clinton, Starr wanted to compel Secret Service agents on the President’s Protective Detail to testify about what they may have seen or heard regarding the president’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Secret Service Director Lewis Merletti argued that having agents talk about anything other than criminal acts would be a breach of the “trust and confidence” tenet vital to the protection of the presidency.

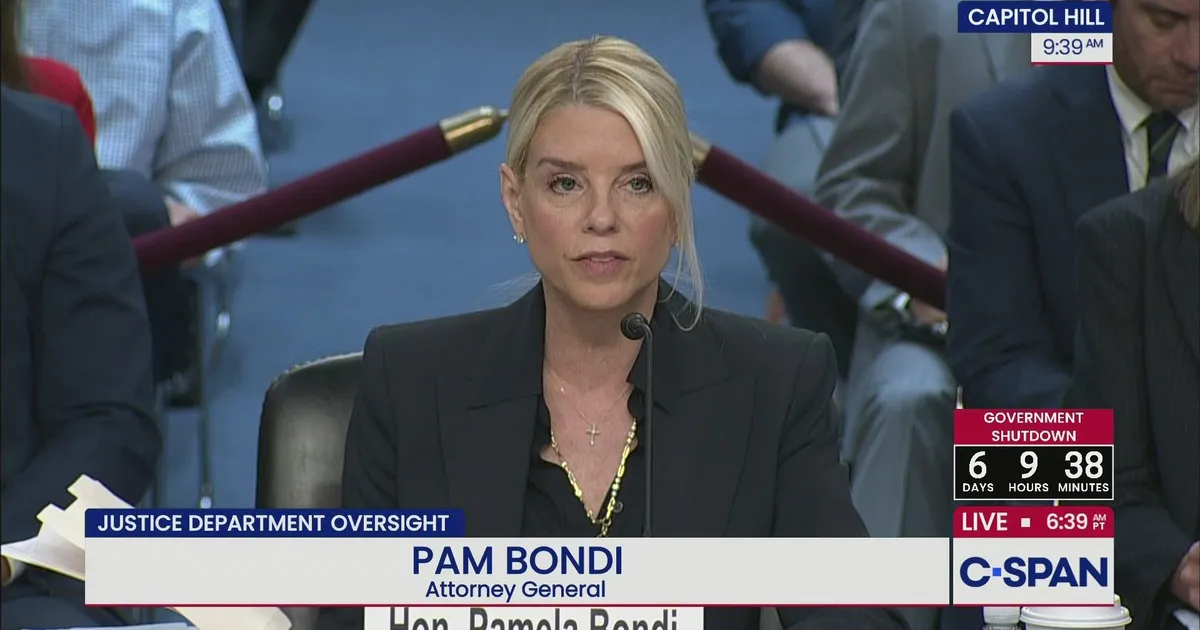

Shocked after his initial meeting with Ken Starr, Merletti seeks a meeting with Attorney General Janet Reno.

Merletti follows closely behind President George H.W. Bush when he served on the President’s Protective Detail.

Leaving the independent counsel’s office, Merletti told Kelleher that he wanted a meeting with Attorney General Janet Reno. He wanted to stop any further actions by Starr before they could get started and felt that Reno would look at his presentation and clearly understand the stakes involved.

However, before that meeting, Merletti called a conference of several living, former directors. After listening to Merletti detail Starr’s plans to subpoena agents to testify about the president’s personal life, John Simpson, the Service’s 16th director, was the first to speak.

“Let me explain something to you. You see that chair?” Simpson said forcefully, pointing to the director’s chair at the other end of the room. “When I sat in that chair, this Secret Service lived on the principle ‘of being worthy of Trust and Confidence,’ and I think I speak for all the other directors here, agreed?”

Everyone in the room spoke with one voice, “Absolutely!”

With the full support from the former directors as well as the former special agents from the president’s detail, Merletti and Kelleher walked into a conference room at Justice to confer with Janet Reno.

Near the end of Merletti’s presentation, Reno looked at a video of a 60 Minutes interview between Mike Wallace and Clint Hill, the Secret Service agent well-remembered as the man climbing on back of the presidential limo in an attempt to save President Kennedy in 1963.

Prior to his presentation, Merletti met with Hill to discuss a rarely seen photo of Hill on the back bumper of the President’s limo the day of the Kennedy assassination, but in later images, he’s not there. Hill explained that one week earlier, Kennedy had ordered agents off the back of the car. Kennedy said that the agents were “creating a barrier between the people and the president.”

“How did you end up on the back of the car, four days later?” Merletti asked.

“I can’t tell you what it was, Lew, a sixth sense,” Hill began, “but something was wrong that day. I didn’t think that the president was going to be shot. I just didn’t feel comfortable. “Within minutes,” Hill said, “it’s overpowering, again… Then, I hear it…” Hill made a clapping sound with his hands. “I knew, right in my gut.”

Hill jumped off the follow-up car and raced to Kennedy’s limo, but it was too late.

“Lew,” Hill solemnly tells his director, “don’t let Ken Starr do this. We got pushed away by the president. Don’t let another agent follow in my footsteps. Promise me that you’ll fight this.”

“I promise.”

Clearly moved, Reno continued to stare at the screen. “Very powerful, very convincing; very, very powerful.”

That evening, Merletti got a call on his White House telephone from Deputy Attorney General Eric Holder. “I don’t know how you’ve done this,” Holder said, “but in the course of 24 hours you have convinced the entire upper echelon of the Justice Department that you’re right. You mean to tell me that you gave the same presentation to Ken Starr?”

“Yes!” Merletti replied.

“We find it hard to believe that he couldn’t see this.”

“I’m telling you, Eric, I gave it to him two days ago!”

“Well,” Holder said, “tomorrow you’re giving it to him again and we’re coming with you.”

The next day, Merletti and Kelleher, along with a contingent of attorneys from Justice, returned to OIC to watch the Secret Service director repeat his entire presentation to Ken Starr.

“Mr. Merletti,” Starr began, “this office has great respect for the work you and your agents do. Now,” he says, pulling out a floor plan of the East Wing of the White House, “I’d like you to tell me how agents at the White House are stationed around the family movie theater and what they can see and hear.”

“In every presentation,” Merletti told me, “[Starr] would get up and say, ‘I totally respect Lew Merletti and everything he’s done.’ There was no respect there. It was all rhetoric. It was all hypocritical. He couldn’t care less. So we go to court.”

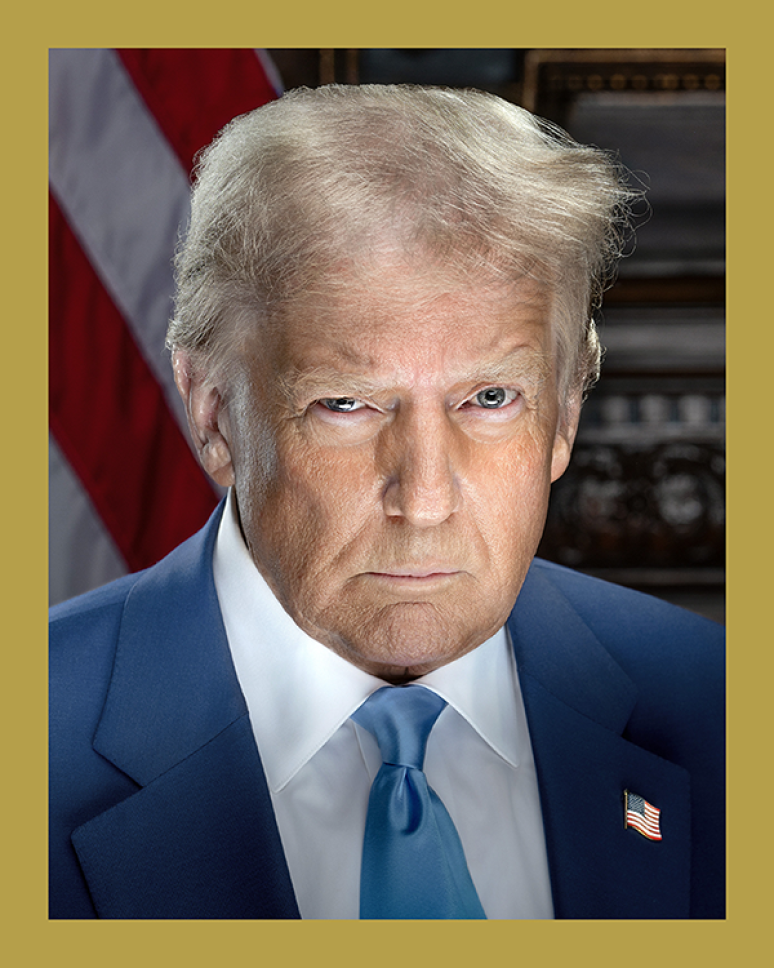

Sometime in late March, Merletti received a call from former President George H.W. Bush who had been watching news accounts on the issue. “This isn’t right,” Bush told him. “You’re right. Ken Starr’s wrong.”

In a personal letter to Merletti from Bush dated April 15, 1998, the former president wrote:

Dear Lew, I have intended to write you this letter for some time, but today’s newspaper coverage regarding the Secret Service’s being asked to testify now prompts me to move ahead. …

If a President feels that Secret Service agents can be called to testify about what they might have seen or heard, then it is likely that the President will be uncomfortable having the agents nearby. … What’s at stake here is the confidence of the President in the discretion of the USSS. If that confidence evaporates, the agents, denied proximity, cannot properly protect the President.

Feel free to use this letter with the proper authorities in the special prosecutor’s office, or should the matter go to court, with the proper officers of the court.

Bush sent a copy of his letter to Ken Starr with a note attached: “Don’t do this. Merletti’s right!”

“It didn’t mean a thing,” Merletti said. “Not a thing.”

With the help of DOJ, the Secret Service goes to court. They lose in the D.C. district court and the appellate court. Early in July, Kelleher and Merletti meet with Solicitor General Seth Waxman, the attorney who represents the federal government before the U.S. Supreme Court.

As Merletti remembered, “I’m called over to the Justice Department, and – I’ll never forget this – we go in, big conference room, me and Kelleher, and about eight, maybe more justice department attorneys and Waxman walks in. ‘We’re not taking this to the Supreme Court,’ he says. ‘We lost in district court; we lost in appellate court. We’re done.’ ”

What the Secret Service was seeking, what DOJ was fighting for was a “Protective Function” privilege similar to doctor/patient and attorney/client confidentiality. Due to the proximity necessary between agents and the president, they argued, any conversation agents overhear should remain confidential, and similar to the doctor/patient relationship, they should not be compelled to reveal such conversations in a court of law. The only exception is if an agent witnesses a crime.

“If we saw a crime,” Merletti said, “you wouldn’t have to ask us. We’d report it. I would have been the agent in-charge of the President’s detail. I would have gone to my director, and I would have gone to the Secretary of the Treasury. But we hadn’t witnessed a crime!

“Now, we’ve got this guy, Ken Starr, asking us, ‘Was that woman’s lipstick on straight?’ You think we’re looking at someone’s lipstick? We’re looking for terrorists. Bin Laden was on our radar screen. We’re ready at any moment to respond, and you want us to watch people’s lipstick and hair?

“Agents are posted around the Oval Office. However,” Merletti stressed, “number one, you can’t see inside; and number two, you can’t see the other post. You don’t know who’s in the Oval Office, and you don’t care, as long as they walk by and have a badge that has the right encryption on it. That’s all you care about.”

While Merletti appreciated Waxman’s professionalism in the matter, he was not prepared to give up the fight.

“If you give up,” Merletti told the Solicitor General, “I will go to the American people. I will not let the men and women in the Secret Service who have vowed to give their life to save the life of President of the United States… If they’re willing to fight that way, you think I’m going to back down? We’re going to fight and fight and fight!”

With that, Merletti and Kelleher leave the room. But before they could reach the end of the hall, an attorney called them back. “Okay, you’ve convinced Waxman. We’ll go to the Supreme Court.”

Friday’s conclusion: the Supreme Court’s ruling, and the unimaginable twist that takes place after Merletti retires.

Comments

Leave a Comment

Jim, when folks lack a sense of objective thinking, outcomes are mired in what’s fabricated or created to bolster their limelight status.

It wasn’t bad enough that the Lewinsky matter made the country take sides in President Clinton’s alleged misconduct but, it was rationalized to be acceptable because he wasn’t elected to be a Puritan and as he said, “I didn’t have sex with that woman, Monica Lewinsky.” That statement and the rationale that oral sex was not sex, catapulted the news coverage into every home in the country. Today, high school students don’t see oral sex as sex. Today, the argument supports the permission to do anything.

As one reads the article, it clearly shows that integrity lost its way and Merletti held his compass true to his convictions.

Thank you for posting this review of an example of the Shakespearean dramas that continue to plague our Halls of Power in our United States democracy. Reading this article draws my attention to the miserable current condition of “governance” as it is demonstrated by both the in-office and hoping-to-be-elected players. Have we replaced adult ethics with adolescent popularity contests? Did Ken Starr’s development freeze at age 15? Is everyone in our nation’s capital infected with a Ken Starr ethical virus? I hope to get the answers to these questions in the second part of the article!

Wow, this is an intriguing story! Personalities, egos, winning or being right all above the truth. I am sure the full story is a book, but I eagerly await the third part.