To begin with… it was cold. The kind of cold that makes a New Hampshire apple snap with juicy flavor. Unfortunately January is not apple time, and I was not there to enjoy the fruit of the state but the fruit of knowledge. (I know… I know. This explains why I’m not Robert Frost.)

I arrived at the New Hampshire Technical Institute in the historic town of Concord to participate in teaching thirty-six nursing, criminal justice and other students Contemporary Ethical Issues, a week-long class offered by Professor Stephen Ambra. Ambra has been using my book, What Do You Stand For? as preliminary text for the course since the book’s release in 2005.

The students’ pre-class assignment was to write a paper detailing a story that they connected with in the book.

“‘The unexamined life is not worth living,’ Valerie writes. “I started to examine my life as Socrates suggested: “Responsibility – we need to look internally before we push the blame on someone else, own up to our mistakes and learn from them.

“Caring – stick up for those who cannot stick up for themselves. What happens when a bully picks on the little guy? That’s where I believe that someone – that someone being me– needs to step up and say, ‘This is wrong!’”

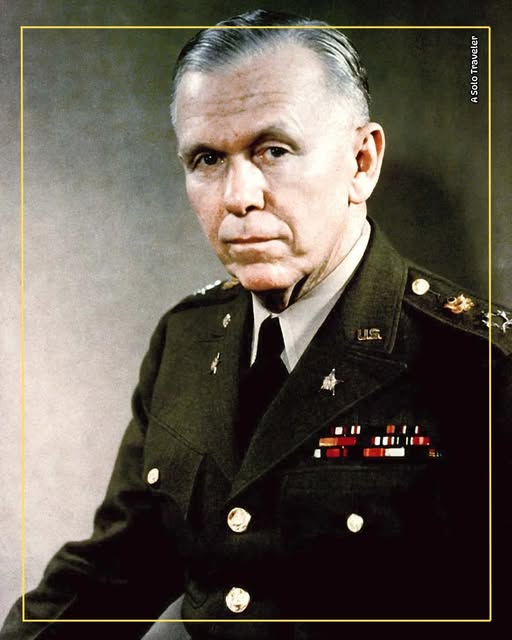

“Ponder the soldier, contributor Dale Dye wrote in the book, “If he’s willing to die for you, be worth that sacrifice.”

Elizabeth, a former government agency worker writes, “Dye made me realize how important it is to believe in what I stand for and stand for what I believe.”

“Everyone has general ethical principles,” Ashley said. “The real test is not in the principle itself but in how you use that principle in life.”

“One story that really stood out for me,” Nina offered, “was about living up to the expectations of others and being true to yourself. I can relate to this story, not necessarily my parents telling me what I should do, but me assuming what people think I should be.”

Jeremy writes, “[What Do You Stand For?] I realized that I didn’t know how to answer that question. All my life I have been basically going with the flow, never really taking a stand for anything that I saw that was wrong. I have witnessed people being bullied because of their race or sexual orientations. I have even been the one bulling, occasionally. There is more to life than just going with the flow. Eventually, you have to take a stand for something and do what is right.”

The engagement of the class on a variety of ethical issues was extraordinary. Fully 90 percent of the class – both men and women – actively participated. One such conversation led into the issue of bullying. “How many have been bullied in school?” I asked. Virtually every student raised their hand. After one student shared his own horrific story, he volunteered that the experience at least left him with a great nickname, “Red.”

“We certainly have no ethical duty to hold all people in high esteem,” writes Jean-Pierre, a student from the Congo, “but we should treat everyone with respect… I believe that in order to grow, we must surround ourselves with the variety of people we want to be.”

“This entire book was a wake-up call for me,” Stephanie wrote. “I mean, don’t get me wrong, it’s not like I am not a morally sound person, because I am. It’s just that I’m always trying to find more ways to better myself; to feel as though my life is worth something.”

The more Steve and I would ratchet-up the ethical scenarios, the more involved the students became. The only other time I remember witnessing this much engagement was in my own class of twenty-eight students in ethicist Michael Josephson’s Ethics Corps.

At the end of day two, perhaps Nina said it best. In a variation of Socrates famous line, she wrote, “It is not life that is given to you; it’s what you do with your life.”

Before it was over, the week would reveal more than I expected.

Comments