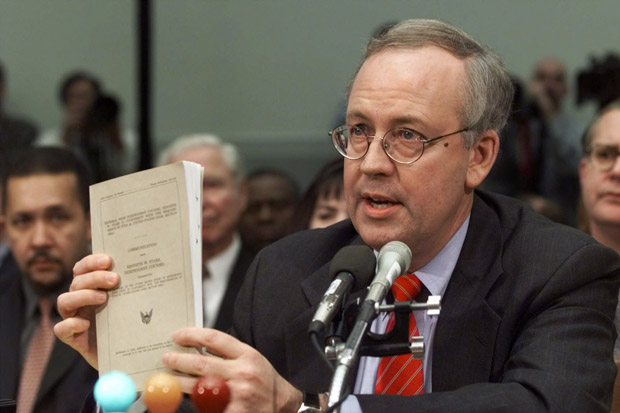

On Thursday, I explained how, after a 19-month Freedom of Information request, I obtained a copy of the only independent investigation examining allegations of misconduct in Ken Starr’s Office of Independent Counsel. Former Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division Jo Ann Harris and her Co-Counsel Mary Harkenrider spent 10 months and conducted 25 interviews during that investigation.

In my own investigation into these events, I interviewed Harris many times in an effort to not only understand the context of Starr’s Office but the details behind the incredible back-story as to what happened to her report after she delivered it to Robert Ray, who took over as independent counsel after Starr left.

In January 1998, while the OIC was in the process of wrapping up old cases against President Clinton that were going nowhere, a call came into the office giving them the viable lead against the president they were looking for. Linda Tripp told them that former White House intern, Monica Lewinsky, who had an affair with the president, had lied on an affidavit in the Paula Jones civil suit. The OIC immediately sprang into action to confront Lewinsky.

Friday, January 16, 1998 – Before the Lewinsky Encounter

Two DOJ attorneys arrived at the Office of Independent Counsel at about 9:30 a.m. “after a high level meeting at the DOJ where it was decided that OIC needed an expansion in order to proceed.”

As Harris explained in an interview, “There are two ways that the independent counsel can expand the jurisdiction that the court gives them: One, they could’ve declared it themselves as related, or they could get the Department’s referral [agreement], and it was very important for Starr to get the Department to agree. It was terribly important. If they’d gone ahead without the confidence there might have been an entirely different kind of litigation going on.”

While awaiting Starr, the DOJ attorneys had a conversation with three OIC lawyers as well as the lawyer designated as “the speaker” who would actually confront Lewinsky in the hotel room. The Justice attorneys were told that all four OIC lawyers “… had listened to parts of the new Tripp tape and it contained even stronger and more explicit evidence of witness tampering.” However, “Unnoticed, ignored, or simply regarded as not relevant in this taped conversation is Tripp’s comment to Lewinsky that ‘you didn’t even tell your own attorney… ,’ indicating again that Carter was not in on the scheme.”

After Starr arrived, at about 10:00 a.m., he and one of the DOJ attorneys called Judge David Sentelle, the presiding judge of the Special Division. “[They] explained that the matter involved an emergency investigative situation and asked for a verbal order expanding the OIC’s jurisdiction pending the submission of appropriate documents later that day. Sentelle said he would consult with his two colleagues and get back to [them].

At 10:33 a.m., the Special Division gave the OIC the expansion they were seeking. They had the go-ahead to investigate Lewinsky. With the stage set, the plan for confronting Lewinsky now shifted into high gear.

“Tripp had arranged to meet Lewinsky at 12:30 p.m. at Pentagon City; two rooms had been reserved at the Ritz Carlton; and the equipment was ready for phone or body recording. [An FBI agent] proceeded to lay out a game plan. Tripp … would be wired, and ‘[If] Monica stops interview midstream, we’ll send her out – e.g., if [she] says wants attorney – we’ll have Linda come in screaming and they leave together, [Tripp] taping.’

Harris and Harkenrider’s investigation emphasizes, “Although this suggestion again indicated that the agents had concerns about what to do if Lewinsky asked for her lawyer, there was no further discussion of other potential courses of action in this regard.”

However, the notes “do not record any reaction to [the speaker’s] suggestion that if Lewinsky asked about calling her lawyer, they would say that it would decrease the value to her of cooperation, and it became the centerpiece of the OIC’s strategy to keep Lewinsky from calling Carter.”

The Lewinsky Encounter

The OIC lawyers and their agents headed over to the Ritz Carlton sometime before 1:00 p.m. The lawyer designated as “the speaker” rode with another lawyer separate from the agents. On their way over, “the speaker” cautioned his colleague “about the risks of the confrontation and that they needed to be especially careful not to cross the ethical line.” Asked to clarify, “the speaker” said that they should not disparage Lewinsky’s attorney, Frank Carter.”

The two agents arrived at the food court at around 1:00 p.m. As they showed their credentials, Tripp faded into the background. One agent informed Lewinsky that “she was in trouble and that she was the subject of a federal criminal investigation. According to [one of the agents] she said: ‘go fuck yourself.’ ”

After the agent explained that she was not under arrest, but that “agents and attorneys wished to discuss her culpability in criminal activity related to the Paula Jones civil lawsuit,” Lewinsky said, “I’m not talking with you without my lawyer.”

If she were to get a lawyer, the agent explained, “we won’t give him as much information and you won’t be able to help yourself as much.” Lewinsky and the agents agree that they told her that she was not under arrest and free to go

Lewinsky followed the agents upstairs shortly after 1:00 p.m.

According to the report, “The written record of what occurred between 1:05 p.m., when Lewinsky arrived in room 1012, and when she left with her mother almost twelve hours later is sketchy at best.

“Lewinsky says that right after [the speaker] introduced himself, she said something like ‘I want my lawyer,’ or ‘I’m not talking to you without my lawyer,’ or ‘can I call my lawyer?’

“[The speaker] remembers none of this, but tells us that it would not have changed his analysis of the contacts issue. He says ‘it was pre-indictment anyway,’ and because of that ‘even if she had said that ‘he represents me in the criminal case,’ it would not have made a difference.

“[The speaker] began his pitch stating that it was an OIC investigation and that it involved the Paula Jones case. Lewinsky says that [he] told her the… case involved perjury, obstruction of justice, witness tampering, subornation of perjury and conspiracy. He told her that if she cooperated, the government could bring no charges at all, or file something with a judge who could reduce her sentence to no jail time or probation depending on the value of her cooperation. Lewinsky remembers that [he] kept telling her that the matter was time-sensitive.

“Between periods of crying, Lewinsky asked a number of questions about ‘cooperation made known’ and also about calling her attorney, Frank Carter.”

The pitch wrapped up around 2:45 p.m.

With the Isikoff deadline approaching, “the speaker” offered Lewinsky full immunity for full cooperation. However, Lewinsky still had questions: “Should I get an attorney regarding the immunity thing?”; “I don’t understand why Carter being my attorney in the Paula Jones case doesn’t make him my attorney on this.”; “[If] there is a difference in the criminal and civil case, what kind of attorney should I get?”; “I might want Frank Carter for this.”; “Wouldn’t Carter be good?; Can’t he do criminal law?” At one point, “Lewinsky suggested taking a taxi to her attorney’s office.”

One of the agents told Lewinsky, “It is obvious he is a civil attorney because he represents you in a civil case; you should go to someone who is experienced in federal criminal law; we don’t’ know about his experience.”

While it may be unclear whether any of the OIC attorneys and agents directly disparaged Carter, they were clearly directing Lewinsky away from contacting him. In a footnote, Harris and Harkenrider point out that both “the speaker” and an agent “at some point explained to Lewinsky that the civil and criminal cases were separate and that Lewinsky could not be represented in the criminal case because she did not know about it.”

While the OIC lawyers and agents may not have crossed any legal boundaries, they were clearly taking advantage of Lewinsky’s lack of legal knowledge to both dissuade her from contacting Carter and persuade her to fully cooperate in an undercover scheme to trap the president. “We are troubled,” the report states, “that [the speaker] did nothing to avert the implication regarding Carter’s experience when the OIC knew nothing about Carter, not having researched his background.”

Harris explained, “It’s one thing not to analyze a very complicated Department policy about ‘contacts with represented persons’ and whether or not Carter fit into that, but it’s quite another when a person repeatedly talks about different ways of contacting their lawyer: ‘I want my lawyer.’ ‘Can I see my lawyer,’ down to, ‘Let’s just go over to his office.’ I can’t think of a prosecutor who would not just stop after this.”

At approximately 3:00 p.m., “Lewinsky said that she needed to talk to someone else – ‘my attorney,’ or ‘my mom’ or ‘something like that’ before making a decision.

“To demonstrate that they were not attempting to keep Lewinsky from consulting with a lawyer other than Carter, the OIC submissions to the court, to Congress, to Bar Counsel and to the Department of Justice all rely upon the fact that they gave her the number of the legal aid society or public defender’s office.”

Lewinsky says she didn’t trust the attorneys in the room.

After getting nowhere, “the speaker” called in a reinforcement OIC lawyer around 3:30 p.m. whose approach, the report describes, was “more emphatic.” After this new lawyer told Lewinsky that time was running out, Lewinsky said, “How can I make a decision if you won’t let me call anyone?”

The lawyer told her that, “she was a grown-up and that she did not need her mother to make a decision.” With that, he left the room.

Frustrated by their complete lack of progress, the OIC lawyers allowed Lewinsky to go downstairs to call her mother without forfeiting the immunity offer. When Harris and Harkenrider asked why she didn’t call Carter at that point, “Lewinsky said that she was afraid she was being followed, that the downstairs phones were tapped and that she would lose the opportunity to help herself.”

Lewinsky returned to the room at approximately 4:12 p.m. and finally reached her mother, Marcia Lewis, by phone. Lewis told “the speaker” that she would travel to Washington by train to meet with them at the hotel.

With her mother en route, Lewinsky asked if the immunity offer would remain valid if she contacted Carter. “The speaker” explained “that complete immunity required complete cooperation, and meant that ‘we don’t want you talking to anybody.’ He told her that she could go back to ‘cooperation made known’ if she wanted to call Carter.”

Lewis arrived at 10:20 p.m., and after speaking with her daughter and the lawyers, she called her former husband, Lewinsky’s father, Bernard Lewinsky. “Within an hour, Bernard Lewinsky told the OIC lawyers that William Ginsburg represented his daughter. After a brief and unfruitful conversation about immunity, the evening ended at 12:45 a.m., and so did the OIC’s hopes of conducting a covert investigation.

“Months of negotiation would pass,” the report records, “before Lewinsky was eventually given the full immunity offered to her by ‘the speaker’ on January 16, 1998.”

* *

Weighing the evidence from 25 interviews, their report concludes that “no OIC attorney committed professional misconduct … Under the OPR’s analytical framework, such a finding is compelled by our finding that the applicable regulations and standards do not provide a clear and unambiguous answer to whether Monica Lewinsky was ‘represented’ regarding the subject matter of the OIC investigation … ”

As to the question “Was Lewinsky a represented person?” the investigators found that “Under the regulation, a ‘represented person’ is a person who has retained counsel, where the representation is ongoing and ‘concerns the subject matter in question.’ ”

The OIC’s premise was that while Frank Carter represented Lewinsky in the civil matter concerning her affidavit for the Paula Jones case, Carter was not representing Lewinsky about her criminal activity related to that case. Since this investigation was only four days old, neither Lewinsky nor Carter could know of it. “Therefore, [the OIC] reasoned she could not be represented as to their investigation.”

The investigators state, “We find that neither the regulation, its commentary, nor other Department materials, provide a clear and unambiguous answer to [the] question [of whether Lewinsky was represented by Carter].”

Notwithstanding the legal definitions, OIC seemed to be skirting ethical lines throughout these events. In fact, the OIC lawyer who led “the pitch” to Lewinsky had been a Department ethics trainer, and in his lectures “consistently urged caution and restraint in considering contacts matters … He talks of the ‘reams of approvals’ required by the rules … [and] emphasizes the need to ‘avoid all appearance of coerciveness or trickery.’ ” In his lecture notes, he spelled out that “It is never OK to continue to ask questions after the person has said he wants his attorney there (even though the DOJ position seems to permit it).”

The report’s summary concludes: “We have found poor judgment in [the speaker’s] overall stewardship of the confrontation with Lewinsky… specifically: [he] was certain: ‘She’s not represented in this case and it is pre-indictment.’ He was so certain he saw no need to take the elementary step of reading the rules he was interpreting. By his own admission, [he] rendered his opinion after a mere 5-10 seconds, having assumed from the beginning that Carter was ‘the civil guy, not the criminal guy and beyond that didn’t spend much time thinking about it.’

“[The speaker’s] analysis failed in three respects. First, [he] failed to appreciate, and therefore to alert the OIC that whether Lewinsky was represented could be considered a close question; second, he was wrong in asserting that because it was pre-indictment, there was no problem; and third, his certainty had the effect of cutting short thoughtful consideration of all of the other issues implicated by the presence of an attorney.

“There is no question,” the report continues, “…that Lewinsky had an attorney on January 16, 1998. There also can be no doubt that the approach to Lewinsky was entwined with the very subject of her representation by Carter, her potential testimony and affidavit in the Paula Jones case. Certainly there were attorney-client issues to be skittish about, whether or not they fit within the black letter of the regulation.”

In looking at the overall context, Harris and Harkenrider point out, “We understand the apparent state of disarray in the OIC office as the confrontation with Lewinsky approached. But we find there was time to consider the broad issues implicated by the fact that Lewinsky had an attorney in connection with the Jones case, including a thoughtful review of the DOJ rules regarding ‘contacts,’ and consultation with attorneys and agents more experienced in ‘bracing’ targets and witnesses.

“This is not the type of analysis and conduct that Starr had a right to expect from his career prosecutors. It exacerbated the public criticism of the Office of Independent Counsel and resulted in unwarranted and distorted public perceptions of the conduct of all federal prosecutors throughout the country.”

* *

Among their key recommendations, Jo Ann Harris and her Co-counsel Mary Harkenrider indicate, “Part of the atmosphere fueling the adversarial relationship between the OIC and DOJ in this case, we believe, was the lack of a clear understanding of how the two offices would relate to each other in [Office of Personal Responsibility] matters. Therefore, we recommend that there be a pre-appointment agreement setting forth clearly the manner in which the Special Counsel’s office and the Department will relate to each other in matters involving allegations of ethical violations by Special Counsel’s attorneys…. we urge that an aspect of it be a strong statement that Special Counsel lawyers owe the investigating authority a duty of cooperation and candor.”

They conclude their report with what they consider to be critical. “We recommend that any future Special Counsel follow the DOJ model and appoint one of the senior full-time lawyers in the office as a Professional Responsibility Officer (PRO). That attorney would be responsible for training where necessary, keeping abreast of DOJ regulations, rules and policies and would be available as an ethics resource for Special Counsel and all of the lawyers in the office.”

After inviting the OIC attorney in question to her office to read the Report’s findings, Harris submitted her report directly to Robert Ray on December 6, 2000. But that’s only the beginning of what turned out to be a long, complex subplot worthy of Alfred Hitchcock.

Next Up: What happened to the Report after Harris turned it into Ray

Comments

Leave a Comment

If there is an unsung hero here, other than Mr. Ethics, it is Jo Ann Harris. Her story is fit for the big screen.